17.10.2020

Black Lives Matter

Reflections On Juneteenth, 2020 (*)

By Ahmed J. Davis

My deposition trip in January to rural North Carolina was a quick one. A day down, a half-day deposition and a quick trip back. When I got there and checked in, the kindly thirty-something white woman at the front desk greeted me with a welcoming smile. The name badge pinned to her shirt identified her as Mary. I handed her my identification and a credit card; her smile widened considerably, I would soon learn, because the Maryland driver’s license she then held identified me as a Davis. Well, that’s just the most fabulous last name in the world, don’t you think? Clearly, she was a Davis, too. I half-smiled back and agreed after she confirmed my suspicion. As she processed me in, she had no way to know what I was thinking: that she held my Maryland license because I was a son of Baltimore, as was my father before me, and his mother a daughter of Baltimore before him, but that her mother—my great-grandmother Olivia, affectionately known as Grandma O—had come from a different place, and a different time.

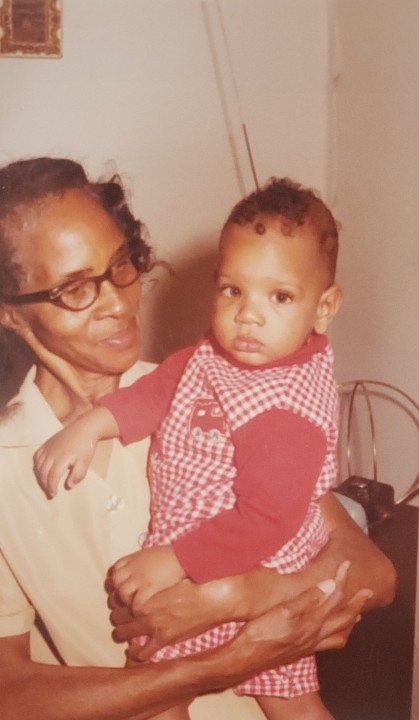

Grandma O was born in 1908 and eventually married Roy Davis, both of them from rural North Carolina, in a small town honestly not too far from where I then stood. In that moment, I could not help but think about her, the woman who watched me after my half-day kindergarten classes until my young parents could get off work to scoop me up. The woman who, I one day would learn, had herself been fortunate enough to spend time in her young life with her great-grandmother, a woman who Grandma O told me had been born a slave. So there I stood, deposition in mind yet still pondering this: I am, in 2020, blessed and fortunate enough to be a full equity principal and erstwhile Management Committee member at the best IP law firm in the world—still having been raised by a woman, who was raised by a woman, who was born a slave. So it turns out that the reason that I may share such an admittedly fabulous last name with my friend Mary just could be that one or more of her forebears owned one or more of mine. A very real, palpable, spin on six degrees of separation.

You see, in context, it hasn’t really been that long. And I am hardly the only one of us that could tell a story like that. We in the Black community celebrate Juneteenth as an important date of de jure change, but we as a country have yet to fully realize the de facto aspects of what Juneteenth ought to represent. Even in 2020, are Black people in this country really free? Juneteenth is cause for celebration, but have the post-Civil War Amendments to the Constitution really borne more enduring fruit than the strange fruit Billie Holiday sang about? Southern trees bear a strange fruit, blood on the leaves and blood at the root, Black bodies swingin’ in the southern breeze, strange fruit hanging from poplar trees….

You see, in context, it hasn’t really been that long. And I am hardly the only one of us that could tell a story like that. We in the Black community celebrate Juneteenth as an important date of de jure change, but we as a country have yet to fully realize the de facto aspects of what Juneteenth ought to represent. Even in 2020, are Black people in this country really free? Juneteenth is cause for celebration, but have the post-Civil War Amendments to the Constitution really borne more enduring fruit than the strange fruit Billie Holiday sang about? Southern trees bear a strange fruit, blood on the leaves and blood at the root, Black bodies swingin’ in the southern breeze, strange fruit hanging from poplar trees….

It is one of the inconvenient truths and existential questions with which this country has yet to fully grapple: the consequences of hundreds of years of physical, mental and emotional subjugation of an entire people, and how that continues to manifest itself, across numerous aspects of our society, even today. Some thought the shouts for Justice were simply about George, Ahmaud, Trayvon, Breonna, and so many others. But we are still crying for Emmett and Martin and Malcolm and Medgar; still in pain about Tulsa and Rosewood, and the Red Summer of 1919; and yes, still wondering what ever happened to that 40 acres and a mule.

Stony the road we trod, Bitter the chastening rod, Felt in the days when hope unborn had died, Yet with a steady beat, Have not our weary feet. Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

The Black experience in America cannot be cabined into one view, espoused by one of our delegation, or conferred to someone else. We are, even amongst ourselves, diverse in background and pedigree and politics and viewpoint and even color (which, undoubtedly, can be directly tied to some of the more heinous consequences of slavery raised above). If you polled our Black colleagues, they like me have probably bristled at the question most of us have heard, which invites of one of us to speak on behalf of all of us: please do tell us, what do Black people think about _____? Circumstances are far more complicated than for me or anyone to give a single coherent answer on behalf of an entire racial community. But do not confuse the actions of some with the goals of all. Some march peacefully and pray continually, while some take a decidedly less passive approach. A right-minded individual neither condones nor engages in looting or harming others, and at the same time can fully embrace the impulse to riot and thereby speak in what Dr. King called the language of the unheard. Perhaps Frederick Douglass put it best when he spoke upon the cost of real freedom: Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning.

Regardless of class, or education, or geography, or personality, for clear historical reasons, we recognize that as a people we have been mistreated in and by this country, even while remaining largely faithful to the country—especially in the military—for longer than we can account. Black folk like me struggle because I know that this is, at once, both the greatest country in the world—yea, even now—and a nation in need, desperate need, of true healing and reconciliation, aiming for lasting racial harmony, rooted in structural commitments by both the governmental and private sectors to genuine equality. But that comes first only with an acknowledgement of what the past has wrought, and second, with true efforts at lasting change. One of the many reasons there has been and is so much anger, frustration and hurt is because Black deaths at the hands of law enforcement—or those who view themselves as such (e.g., George Zimmerman and the McMichaels)—are both entirely unnecessary and avoidable, and usually have been met with indifference, bromides, or empty promises of change. And we know this stain is not merely of recent vintage. What so many are now opening their eyes to, reacting viscerally and in horror, has been the lived experience of Black Americans for a long time.

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered. We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered. Out from the gloomy past, ’til now we stand at last. Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

During an interview four years ago on The Late Show, famed actor Will Smith shared something with Steven Colbert’s audience that Black folk innately have known since at least the advent of the iPhone. He said: Racism is not getting worse, it’s just getting filmed. You see, by then, we had seen Eric Garner choked out in New York for allegedly selling single cigarettes, pleading 11 times I can’t breathe. We also had seen Walter Scott shot in the back in South Carolina and had seen the police officers plant a weapon near him. Soon thereafter, we would see Philando Castile shot by an officer while sitting in the driver’s seat, effectively in real time on Facebook live. And the list, troublingly, goes on and on. Separately, we also would come to learn that Dylann Roof, after killing the pastor and members of a Black church in South Carolina during Bible study, was taken into custody peacefully and then inexplicably given a Burger King snack on the way to being booked. Our lived experience is not the experience of others.

Is every Black person harassed or mistreated by police? Of course not. Is every white person given an unfair benefit every time there is an encounter with the police? It would be foolish to think so. But understand this: every police officer does not have to be racist in order for there to be a systemic problem with racism in law enforcement. Indeed, there are very good cops who protect us every single day. The mere fact of their existence, however, does not negate the historical and institutionalized biases that have caused people to take to the streets. So many of us have caught a DWB—Driving While Black—and been the subject of a racially-profiled detention that it has become the butt of jokes. That we, Black parents, have to educate our children—and especially our Black sons—on ways to behave when around law enforcement is a sad but real testament to the world in which we live. Every Black person reading this has been told, or said, some variation on this hurtful theme: you simply cannot do what your white friends/colleagues/coworkers do; the rules for you are different. They are. Black people know it. I like to think white people who are honest with themselves probably know it, too. As a result, we rarely, if ever, feel comfortable bringing our authentic selves to a public environment—including into the workplace.

The overwhelming use of avoidable lethal force by law enforcement in this country against people of color, and Black people in particular, is reprehensible and must change. And we are hopeful that, to quote Sam Cooke, a change is gonna come—but we have been here before. But please understand that it is not just about policing per se. As terrible as the George Floyd and similar situations are, what happened in New York’s Central Park the same day Mr. Floyd was murdered actually is more insidious, with the potential for equally wretched consequences. You see, despite the deadly and unnecessary police overuse of force, the vast majority of us don’t come into contact with police on a regular basis. But we interact with everyday people all the time. When a white woman takes umbrage with a Black birdwatcher who simply asks her to leash her dog, and calls the police to falsely accuse him of threatening her life, that dredges up 150+ years of this country’s post-Civil War ugly racial history and again weaponizes it. It brings up memories of a young Emmett Till being lynched and castrated for allegedly whistling at a white woman; it calls to mind the devastating race riots such as Rosewood, initiated after a false allegation of rape by a white woman against a Black man. The unspoken threat in Central Park that day was palpable and real: I am calling the police and when they get here you will be a target and possibly end up like George Floyd, who died later that very day, 1200 miles away. Recent events have shown that no Black person is immune from this phenomenon: whether you are meeting at a Starbucks in Philadelphia, or barbecuing in the park in Oakland, or golfing in central Pennsylvania; whether you are a little girl with a lemonade stand or even a world-renowned Harvard professor standing on your own front porch—you can get arrested. And if you are Black, that means you could die. In my view, this remains the truest measure of danger we feel and are scared of—everyday people we encounter who try to use their whiteness against our Blackness in that way, as a cudgel.

God of our weary years, God of our silent tears. Thou who has brought us thus far on the way. Thou who has by Thy might, Led us into the light. Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Mothers hold a special place in our hearts. Nowhere is this more true than in the Black community, where mothers hold a revered, sacred place. We have always loved our mothers. And this, too, can be traced in many ways back to slavery—when slave owners tried to keep control by dehumanizing and subjugating Black men and father figures, in particular. Strong Black women have been holding Black families together for hundreds of years, many because they were able to, all because they had to. For many of us, the strongest person we know is a Black woman. And so it was completely understandable, and unsurprising, and gut-wrenching, to hear Mr. Floyd—as a 46-year-old father of five—call out for his own dead mother in the waning moments of his life. Black mothers felt that in a way that only they truly can comprehend. Black men felt that in a way that was beyond real. I cried.

Black mothers not only have kept Black families together, physically and emotionally, but also spiritually. When a people have been oppressed and mistreated for so long, that spiritual grounding is what has made the difference for so many. It’s why so many Black historical leading figures were ministers and clergy. And that’s good because the ultimate issues we are dealing with as a country are issues of the human condition—issues of sin. Those who know understand this means that, while it is painful and Black folk have long suffered, there is joy in the morning. The Negro Spiritual and Black National Anthem, Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing (most of the stanzas of which appear above, intentionally out of order), eloquently embodies the struggles we endure even now, every day. It’s why in the ’60s some shouted We Shall Overcome, while others sang I Shall Not Be Moved. It is why I said in a recent email that love is the more excellent way. Because He did not bring us this far to leave us. But, we have to make this journey together.

Lift ev’ry voice and sing, ’til earth and heaven ring. Ring with the harmonies of Liberty. Let our rejoicing rise, high as the list’ning skies. Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

In my first address at the Principals’ Retreat after I took over as National Diversity Chair almost a decade ago, I stood in a room unentered by other Black principals—we had no others, a condition we sadly find ourselves in again—and told my colleagues and my friends that to really effect change, we need white people (and especially white men in positions of power and authority) to speak up and speak out. To help. To join the cause. I recall it like yesterday: you could hear a pin drop. Some later told me how moved they were; I know still others privately bristled that they felt I was finger-wagging. Some, I understand, may have felt the same about the quote I recently circulated from Dr. King on remembering the deafening silence of our friends. Hear me, Fish Family: it wasn’t intended to be derogatory then and it isn’t intended to be so now. It is, instead, an express acknowledgement of an unspoken truism from the lived experience of Black people in this country. Change happens when enough caring white folk speak up and speak out. What we see happening now, I believe, is evidence of that. It’s wonderful; it’s hopeful; it’s uplifting; and it is a long time coming.

Before this year, some had never heard of Juneteenth. You may have seen that in the past few weeks many businesses and international brands have made commitments to racial justice. A number of law firms have announced that they will make Juneteenth a holiday going forward. That is movement. That, too, marks the beginnings of change. But for enduring change, we need our white and non-black allies and friends to embrace not only the glory-bound pronouncements of Dr. King, but also to imbue within your souls the words of a less revered but equally important Black icon—Malcolm X—who said: I’m for truth, no matter who tells it. I’m for justice, no matter who it’s for or against.

On this Juneteenth 2020, would that it were that way forever for us all—in word and deed, in spirit and truth.

(*) Published originally on June 21, 2020 by Ahmed J. Davis, see: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/reflections-juneteenth-2020-ahmed-j-davis/?articleId=6680305117125783552

Ahmed J. Davis is Principal and National Chair of Diversity Initiative at Fish & Richardson PC focused on patent litigation

Translation: Susanne Berger (MA) und Dr. Irmtrud Wojak

Contact: info@fritz-bauer-blog.de