Even stronger than the hardship were the people who endured it.

Lore Hepner, granddaughter of Adele and Wilhelm HalberstamRead more:

† 17. November 1943 in Poland, concentration camp Auschwitz

Nationality at birth: German

Nationality at death: German

Husband

Husband

Wilhelm Max Halberstam

* 6. December 1866 in Leipzig† 4. October 1943

Käthe Hepner Halberstam

* 1898 in Berlin† 1982 in Santiago de Chile

Dr. Heinrich Hepner

* 1885 in Berlin† 1958 in Santiago de Chile

Granddaughter

Granddaughter

Lore Hepner Arriagada

* 1929 in BerlinErnst Hepner

Klaus Hepner

Place of the fight for human rights: Amsterdam (Jewish Quater), Concentration Camp Westerbork

Jewish Community

Location: BerlinReason for entry: -

Function / Activity: -

The hope of seeing their children and grandchildren again, who had been able to escape from the Nazis to Chile, strengthened the vital courage and resistance forces of Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam until they were deported to the Westerbork concentration camp. In the concentration camp, their hopes and will to live were shattered.

Right to life, freedom and security

Asylum

INTRODUCTION

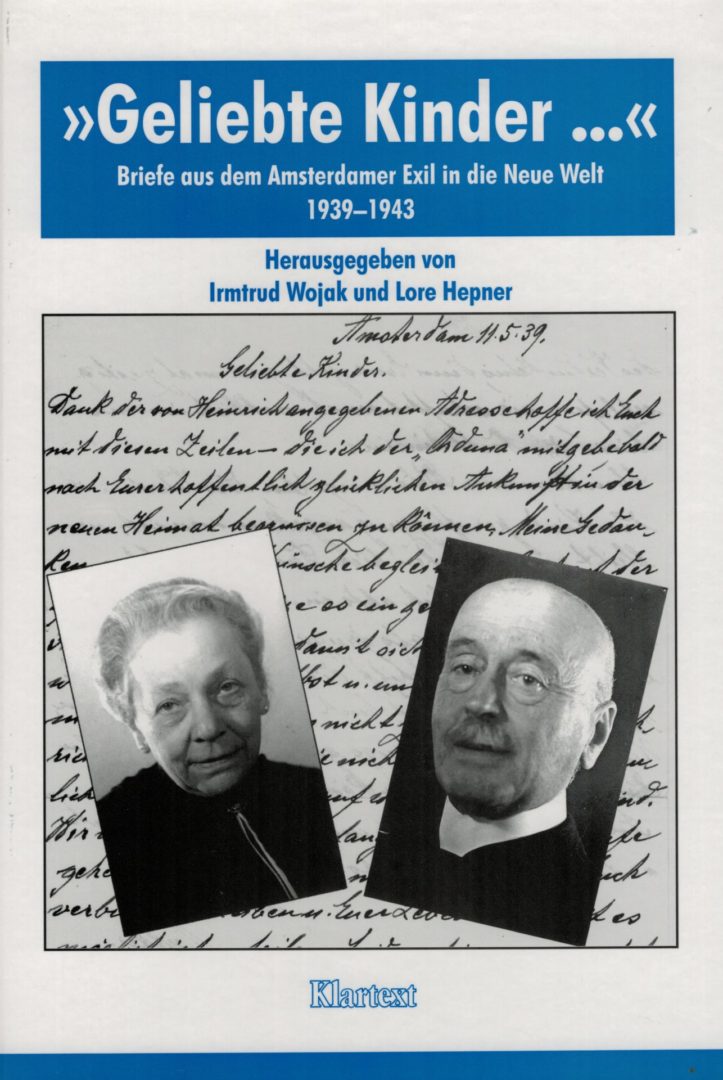

“Beloved children!” began the letters from exile to exile that Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam wrote to their children and grandchildren in Chile from 1939 to 1943. Day after day, Adele Halberstam wrote, she resolved to write in a few words so that one day she would send the letter that would accurately inform the children about life in Amsterdam.

Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam were among those persecuted as German citizens of Jewish faith who, after years of discrimination and exclusion, the Nazi-instigated pogrom of November 9, 1938 (the so-called Reichskristallnacht) finally made them realize that there was no longer any possibility of survival for them in Germany. Their letters are extraordinary historical documents, basically a diary of their struggle for survival and great perseverance, written in the double isolation of exile and ghetto. Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam wrote of a lost home, of the experience of having to leave and let go of the land and people they considered the center of their lives. At the same time, their letters testify to a great courage. The attempt to establish a new life in a foreign land and the hope of being able to start anew in South America – with the “beloved children” – even at the age of over 70.

THE STORY

Adele Halberstam and Wilhelm Halberstam

Even stronger than the hardship were the people who endured it

Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam are among the unfortunates whose children became letters during the Nazi era. Their lives as refugees in the Netherlands, whose children managed to escape to Chile, can also only be reconstructed through their letters. Like a diary, the letters testify to the struggle for survival of two aged people against the superiority of the Nazis, from whom they desperately tried to escape.

Adel and Wilhelm’s granddaughter Lore Hepner, whose mother Käthe was the Halberstams’ daughter, kept the grandparents’ letters for decades. At the time of her escape, Lore was just ten years old. She saw her grandparents for the last time in Amsterdam. In a small apartment in the “Jewish quarter”, packed with their Berlin furniture, the two old people had stored everything they could save from Germany.

Lore’s parents managed a brief stopover with her grandparents in Amsterdam during their escape, before boarding the ship to South America with their children in England. Their unwanted journey became a perilous odyssey, while Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam, because they had not obtained a visa for Chile, had to stay behind in Amsterdam with their son Albert.

From the day they said goodbye, they wrote some 250 letters to the “Beloved Children” who disembarked in the Chilean port city of Valparaiso barely two months before the start of World War II: daughter Käthe, son-in-law Heinrich Hepner, who survived the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and had recently been a respected lawyer in Berlin, and grandchildren Klaus, Ernst and Lore Hepner.

SOURCES ABOUT THE RESISTANCE AND SURVIVAL

Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam, like so many Germans persecuted as Jews who had to share their fate, had long resisted the bitter realization that the so-called Nazi seizure of power in 1933 was the beginning of the end of their lives in Germany. Even in exile, they still spoke in their letters of the hope of one day being able to return to Germany. At the same time, they described a world in dissolution, to which the National Socialist “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” dealt the final blow a short time later. Literally at the last minute, they had managed to flee to the Netherlands in April 1939. Here, soon after their arrival in Amsterdam, Adele and Wilhelm witnessed the fatal repetition of exclusion and violence as the Nazis invaded the small country. In his letters, Wilhelm Halberstam called this the “duplicity of events.”(1)

In the introduction to his book about the years of persecution of the Jews from 1933 to 1939, Saul Friedländer emphasizes that the voices of the victims are indispensable. They revealed to us “what was known and what could be known” (emphasis in original). The voices of the victims were “the only ones that conveyed both the clarity of insight and the total blindness of people confronted with a completely new, profoundly horrific reality,” Friedländer writes. (2) Letters such as those of the Halberstams, or even the diaries written at the same time by the young Anne Frank or the nearly thirty-year-old Slavic studies student and gifted writer Etty (Esther) Hillesum, or even the well-known journalist and book author Philip Mechanicus (born 1889), all three of whom lived in the Netherlands and were later deported to Auschwitz, reveal the inner turmoil that Nazi persecution triggered. (3) They are testimonies to the resistance of people who were brutally torn from their securities, but who did not bow, but fought for their right to life and freedom. They wanted to testify to the truth.

Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam described in their letters the daily struggle for survival of the fugitives, although sometimes even writing seemed to exceed their strength. They wrote the majority of their messages to their “beloved children” after the invasion of the Netherlands by German troops, knowing that their mail was now subject to censorship. Meticulously, “treasonous” lines were cut out of the gossamer airmail paper by the Nazis. Some of the Halberstams’ letters were collected, and some were probably lost in the chaos of the war. In early January 1942, the postal connection to Chile broke off temporarily, and in November 1942, it broke off for good. The last messages from the grandparents reached their recipients only after the end of the war. By that time, neither of them was alive anymore, without the recipients of their letters knowing it.

Unlike the Halberstams, the diarists of the time did not have to fear the meticulous censorship of the Nazis, but they did have to fear discovery. For Anne Frank, the diary was a substitute for a best friend whom she called Kitty.(4) For Etty Hillesum, writing served as a means of self-analysis as well as a preliminary exercise in writing. On July 28, 1942, she noted, “I want to be the chronicler of our fate later.”(5) Philip Mechanicus also wanted to be a chronicler. On September 4, 1942, he attended a “revue evening” at the Westerbork concentration camp and wrote: “I’m going, after all, as a chronicler I must not only know what is happening, but how it is happening.”

Although they had to constantly reckon with censorship, the Halberstams’ letters are a highly revealing source about their struggle for survival in Amsterdam – perhaps even because of it. From their hints can be gleaned what no one could say openly. The letters testify to a constant escalation of events, at first from month to month and in the end actually increasing in drama day by day. Accordingly, they found it more difficult to write letters.

On the one hand, the Halberstams had to make clear to their children soon after their departure how urgently they needed visas to Chile in order not to be deported to the concentration camp. On the other hand, they could hardly write openly about what they had just experienced in Amsterdam if they did not want to put themselves in immediate danger or risk the letters falling victim to censorship. While the diaries, similar to the secret records in the concentration camps that were buried or smuggled out by prisoners, openly recorded the truth about what was done to the persecuted, the Halberstams could only address this truth in a concealed way. Some details could only be reconstructed in retrospect together with their granddaughter Lore and with the help of other sources.

THE YEARS 1939/40

Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam fled Berlin after the “Reichskristallnacht” of November 9/10, 1938.(6) They traveled by ship to Rotterdam and from there by train to Amsterdam, where they arrived in April 1939 and where their son Albert had already found refuge in November 1933.

Wilhelm Halberstam, born in 1866 and a successful merchant, was 72 years old at the time of the escape, his wife Adele five years younger. Their daughter Käthe, a chemical laboratory technician by profession, had met the lawyer Dr. Heinrich Hepner in 1920, who had become the youngest lawyer admitted to the Berlin Kammergericht. Since 1912 he had been a partner in the law firm of the then well-known Berlin lawyer Eugen Fuchs, formerly president of the Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens. Käthe Halberstam and Heinrich Hepner were married in 1921 in the Great Synagogue on Fasanenstrasse in Berlin, and in 1929 their daughter Lore was born – the keeper of the letters.

Lore Hepner and her two older brothers Klaus and Ernst were sent on a Kindertransport from Berlin to Rotterdam on February 7, 1939. There they were housed in a camp for refugee children. In the first days of May, their parents picked them up for the onward journey to London. They had stayed behind in Berlin until Lore’s father Heinrich recovered from the concentration camp. Heinrich Hepner had been arrested on November 10, 1938, in the course of the Jewish pogrom, deported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, and finally released on condition that he emigrate. In Amsterdam, as already mentioned, the last meeting of the Hepner-Halberstams took place in May 1939.

The Hepners, like some 13,000 German Jewish emigrants, found asylum in the Andean nation of Chile. The intercession of a diplomat with the president of the Popular Front government brought about permission to enter the country.(7) Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam, on the other hand, who stayed behind in Amsterdam with their son Albert, were henceforth, as Wilhelm wrote to his daughter Käthe on May 11, 1939, among those he always regretted “whose children have become letters”. Longingly, they waited week after week for news, while the grueling uncertainty about their own fate dragged on longer and longer and became more and more unbearable. Their only contact with Chile was through letters. Their chronicle, which they continued even when the connection to South America broke off for the first time in early 1942, began with the following lines:

“…just received (…) the eagerly awaited letter from Liverpool and hurry to send you a farewell greeting to La Rochelle. The fact that your stay in London did not encourage you to stay there does not change the pain of separation and the great concern with which we see you (…) moving into the unknown foreign country without any security of existence. (…). Klaus’ and Lore’s shoes did not come, of course. Unfortunately, I neglected to give you (Käthe) the detached winter lining from Lore’s coat. (…) The children should not forget Grandma Dele. I send you all my warmest greetings and heartfelt wishes for a good, relaxing trip and for constant health, courage and zest for life.” (May 11, 1939)

Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam experienced the first year of their exile in a free country. The fact that it nevertheless remained foreign to them was not least due to the difficult external change. Instead of their spacious Berlin apartment, they now had to come to terms with cramped conditions in Amsterdam South. The residential district was well-kept and had only just been built in the twenties on both sides of the Amstel Canal. In the thirties it developed into a German-Jewish enclave. Here there were “German fashions and German bookstores, German restaurants and German pastry stores, stores selling German sausage and German bread,” recalled Miep Gies, who provided for Anne Frank and her family in their neighboring hiding place.(8) Anne Frank, her sister Margot, and her parents lived not very far from the Halberstams. Like Albert, they too had moved into an apartment in Amsterdam South in 1933.

Despite their “German surroundings,” so to speak, the Halberstams had to mobilize all their strength to live with the losses they had incurred. “The psyche of the Dutch is so vastly different from mine,” Wilhelm wrote after five weeks, “that I cannot even comprehend the people who like it here.”(9) The Dutch, he said, were an “inexhaustible object of study for him, but not always worth studying.” He made most allusions in the letters to this feeling of strangeness that probably every refugee experiences, especially when he does not understand the language of his country of refuge.

The political situation and the Dutch refugee policy were not mentioned in the letters, although the young Albert Halberstam will have informed his parents about it. We hardly learn anything about him, except that he was unable to gain a foothold and was constantly in financial straits. His precarious situation was the main reason for Wilhelm and Adele Halberstam to emigrate to Amsterdam, although they had been in possession of permanent visas for Great Britain since May 1939 (Wilhelm Halberstam, May 8, 1939).

One reason for Albert’s difficulties was that the neutral Netherlands was not an immigration paradise for refugees from Germany in the 1930s. As early as 1933, the Minister of Justice advocated curbing immigration. From June 1937, when a new government took office, there were signs of a further tightening of asylum legislation, in which the Catholic Minister of Justice Goseling played a major role. With the approval of the prime minister, he labeled the emigrants “undesirable elements” in a circular letter in May 1938 that would have to be sent back. Two days after the “Reichskristallnacht”, on November 11, 1938, it was Goseling who informed the so-called “Büro für Grenzbewachung und Reichsfremdlingsdienst” in a secret circular that the border had to remain closed. A conversation between Goseling (who was later murdered in the Buchenwald concentration camp) and the chairman of the “Committee for Jewish Refugees,” which was founded in 1933, revealed that the persecuted persons were to be housed in camps. The Jewish Refugee Committee had to bear the costs of construction.

Around 7,000 to 8,000 refugees were still able to enter the Netherlands legally after the “Reichskristallnacht”. In September 1939, immediately after the beginning of the Second World War, immigration was stopped. From the letters of the Halberstams we learn nothing about these developments, which already in 1939 led to the establishment of a central reception camp in the province of Drente. On October 9, 1939, the first 22 Jewish refugees arrived there. “A town is being built on the Drente Heath,” the press reported, and no one, not even those concerned, had any idea of the significance that the establishment of this camp called Westerbork was to acquire under German occupation.

Exact figures about the first years of immigration are not available. However, according to the Central Residents’ Registration Office, in January 1941 there were about 14,500 German Jews and 7,300 of other nationalities living in the Netherlands, as well as about 119,000 with Dutch citizenship. Of these, we now know that about two-thirds were deported and killed in Auschwitz and elsewhere “in the East” – more in percentage terms than in all the Nazi-occupied countries of Europe.

What most troubled the refugees in Amsterdam was social degradation and enforced inaction. He was always busy, Wilhelm Halberstam wrote on July 20, 1939, mainly writing “partly necessary, partly unnecessary letters.” But since he was “jobless,” which he “deeply lamented,” he could now immediately answer the first report of the children from Chile, which had arrived in Amsterdam.

The financially straitened situation was primarily a consequence of the contradictory National Socialist expulsion policy. Before their emigration, the Halberstams, like all refugees, were deprived of their property by “Aryanizations” and foreign exchange laws, confiscations and “Reichsfluchtsteuer,” so that they arrived in the receiving countries virtually penniless – which only reinforced prejudices and resentments already existing there and in turn made the expulsion programmed by the Nazis more difficult. Barely six months into their stay in Amsterdam, the Halberstams also ran into increasing difficulties. They did not get their assets in Germany free, neither shares nor credit balances at the Deutsche Bank. And this, while the bread basket, as Adele wrote in September 1939, was hung higher and higher after the beginning of the war and many things were rationed (September 11, 1939).

Seven months after arrival, Adele was nevertheless able to write to her daughter in Chile that they had now laid the carpets. Although everything was very cramped, it looked just as comfortable “as we had always been used to.” Moreover, her Wilhelm was gradually settling in more and more, even, as Adele continued to write, “now even clinging to the hope that conditions in Germany will soon become so normal that one could at least visit, if not return (permanently).” (November 15, 1939)

In fact, Wilhelm Halberstam had long since ceased to mention any dislike of the Dutch in his letters. On the contrary, for the time being the subject of further migration seemed to have receded into the far distance for him, which was mainly due to a noticeable change: said in a sentence that the Halberstams wrote on a postcard on August 21, 1939, during an excursion to the surroundings of Amsterdam: “Remember, here J[uden] are not unwelcome!!!”

The reassurance in this regard was over in the summer of 1940, when their country of refuge also fell victim to Hitler’s Blitzkrieg strategy. The war lasted only five days, from the invasion of German troops to the total capitulation on May 17. Then, after a terrible bombardment of Rotterdam, it was all over. A few thousand Jews found themselves caught up again by the Nazis. Just how aware they were of this is shown by the number of suicides in Amsterdam during the five days of the war, over 120 in all – most of them committed by Jewish citizens.(10)

STRUGGLE FOR A VISA, SPANISH LESSONS AND OTHER SURVIVAL STRATEGIES

Highly concerned, the Halberstams asked their children in Chile the very day after the surrender if the Chilean diplomat, so helpful under the “extraordinary circumstances,” could not do something for their parents in Amsterdam?(11) As early as two months after the German invasion, Adele and Wilhelm signed up for weekly Spanish lessons as a precautionary measure (Adele Halberstam, July 15, 1940). From month to month they hoped more fervently for the granting of their Chilean visas – until, a year and a half later, in November 1941, they could celebrate their hundredth Spanish lesson. In desperation, Wilhelm was by now determined to appeal directly to the President of Chile (October 18, 1941).

We learn little about the background of the first months of German occupation policy from the letters. Neither about the German military administration nor about the civil administration, which was still established in May on Hitler’s orders. The top of this German supervisory administration consisted of four general commissars, who were subordinate to a Reich commissar, the Austrian Arthur Seyß-Inquart. Three of the Commissars General were also Austrians and had already distinguished themselves mightily in the so-called Anschluss of their country to the “Greater German Reich.”

Even if the concept of Gleichschaltung and at the same time “self-nazification”, which Reich Commissar Seyß-Inquart strove single-mindedly to realize, failed to the desired extent: there was collaboration in political and economic relations, not least cooperation, which made it possible to press ahead with the persecution of Jews, which had already begun to be forced in the fall of 1940. The persecution of local and foreign Jews in the Netherlands was always carried out efficiently and with great zeal by the German offices and departments involved: “[S]uch was the common denominator on which all concerned could agree.”

The anti-Jewish policy of the occupiers experienced its practical implementation at the administrative and police level by all Dutch state, judicial and police authorities. The discriminatory regulations were no different from those that Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam had known from Germany. In their letters they mentioned numerous measures that were enacted to place the Jews under special law. Only the scene had changed.

There were more reasons why the need to emigrate was becoming more and more pressing. At the end of 1939/beginning of 1940, the Halberstams had learned of the deportation of Jews from Moravian Ostrava to Prague – “the men for the time being without wives and children,” Adele wrote – in which terrible incidents had occurred; mainly because of “the fear of being forcibly deported to Poland” (Adele Halberstam, September 25, 1939 and November 6, 1939). For the first time, a fatal keyword had been used: “to Poland”.

We know today that the deportations that began at that time, as well as the establishment of ghettos, marked the transitional phase from the expulsion policy to the so-called “Final Solution” policy. After the victory over Poland and France, the German Jewish policy aimed only for a short while at “emigration” and at times at a “reserve solution” (keyword “Madagascar”). Thus, about 6,000 Jews – including acquaintances of the Halberstams – were deported from Prague, Vienna, Moravian Ostrava and Szczecin to the “Generalgouvernement” in Poland at the end of 1939/beginning of 1940.

To make matters worse, since the early summer of 1940 the remittances from relatives in the USA, which were urgently needed for the Halberstams to survive, failed to arrive. The old people now had to starve. They did not hide this from the children, but they tried to adopt a more harmless tone: “The famous kitchen master, whose name ends in Hans, and whom we now have a few days a week, we will now probably have to hire on a daily basis,” wrote Wilhelm Halberstam (June 25, 1940).

And a month and a half later about the “completely hopeless wait for subsistence funds” – while rumors suddenly reappeared that Chile visas were again to be forthcoming: “My dearest ones, if the possibility should still be so dear to your hearts, it can by no means be such a matter of life for you as it is for us.” (Adele Halberstam, July 18, 1940) In October 1940, Adele, by now 69 years old, even entertained the idea of learning cheese-making so that she could one day do something useful in Chile; “please don’t laugh!” she begged her daughter (October 22, 1940).

Despite such hardships, the Halberstams created a small circle of friends. When Adele wrote that they lived even more quietly than when they first came here, she was expressing the isolating effect of the anti-Jewish measures (May 10, 1940 and June 8, 1940). What she called a “great migration” had begun (February 6, 1941). They were constantly hearing about escape routes and distant countries: Some wanted to go to the U.S., Quito or Colombia via Lisbon on Spanish and Portuguese transit visas. Others were on their way via Leningrad and Moscow to Yokohama, where, however, many got nowhere (March 4, 1941). They themselves, however, wanted only one thing: to go to Chile; they were too old for anything else.

ESCALATION OF PERSECUTION

The escalating measures of the Nazi regime also affected the Dutch Jews long before the turn of the year 1940/41. Jewish civil servants were no longer allowed to be employed and, together with Jewish employees, were suspended from their posts in November 1940 and dismissed as of February 1941. So-called Jewish businesses had to be registered and their sale approved. On January 10, 1941, all “full, half and quarter Jews” were obliged to register with the municipal authorities for the central population register. The measure was to be completed within ten weeks and at the same time the identification of those concerned was to be carried out: J for so-called Volljuden, B I and B II for “Mischling” (“Bastaard”) of the first and second degree, respectively. Since July 1941, identity cards had to be marked accordingly.

One year later, the registration of Jews in the central population register of the so-called “Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung” (Central Office for Jewish Emigration), which had also been established in Amsterdam in March 1941 – following the example of Vienna, Berlin and Prague – facilitated the preparation of the deportations “to the East”.

Wilhelm Halberstam alluded to the first raids by the “Green (Dutch) Police” in his letter of March 3, 1941, when he wrote that it had now become “uncomfortable.” This had been preceded by clashes between Dutch Nazis and the population in the Jewish quarter. On February 12, 1941, the Reich Commissar’s representative for Amsterdam had the neighborhood sealed off and house searches carried out. The occupying power used the riots as a pretext to establish a “Jewish Council”, which was forced to implement the anti-Jewish measures. After renewed incidents, the “Green Police” received orders for further raids, during which more than 450 Jews were arrested and deported to the Mauthausen concentration camp on February 22-23, 1941.

The raids triggered the now famous “February Strike,” which paralyzed traffic and industry in Amsterdam and some northern provinces, but was brutally put down after two days under the imposition of martial law. It was the first and largest protest action by a non-Jewish population in the territories occupied by the Wehrmacht against the persecution of Jews. It was not mentioned in the letters of the Halberstams – because of censorship.

The Halberstams did not conceal the fact that on April 15, 1941, all radio equipment belonging to the Jews had been confiscated, which hit Adele and Wilhelm hard, since they had often listened to the French and English news. Now they were missing not only music, but also the news source as almost the only connection to the outside world. In addition, since the beginning of February 1941, Jews were forbidden to swim in seaside, beach and swimming pools, and to rent rooms in boarding houses or hotels at seaside resorts. Even more painfully, in September 1941, the Halberstams registered the ban on walking in parks, since the nearby Vondel Park – with their dog “Queen” – had been a necessary escape point for them. The same decree prohibited them from visiting restaurants, cafés, cinemas and cabarets, as well as public libraries and museums, and finally from shopping at public markets.

From today’s perspective, it is clear that the first deportations in the spring of 1941, followed by three more transports of 470 Dutch Jews to the Mauthausen concentration camp by the fall of 1941, set the course for the mass deportations from Amsterdam from July 1942 onward. The Halberstams certainly learned, as did all Amsterdam residents, that the deported Jews had been murdered – ostensibly in retaliation for acts of resistance. They did not address in any of the letters any idea of what life might be like in Poland for the deportees from other countries, for example their friends in Prague. Only the anxious question, repeated in many variations, to the “beloved children” whether the Chilean parliament could not speed up the new immigration law, made it sufficiently clear that they had to leave Europe as soon as possible (Wilhelm Halberstam, June 25, 1940). They filled out questionnaires with which the “Jewish Council” wanted to support their emigration – “all that is missing is permission to enter Chile,” Adele wrote in March 1942. The terrible thing was: at the same time, for the first time, the connection to Chile was completely broken (March 10, 1942).

In spring 1942 the worst fears became true. By now the Halberstams were both over seventy and lived in constant fear “of what God forbid might come” (March 30, 1942). For months they had not had enough money for heating and were starving (May 13, 1942). On April 13, 1942, Wilhelm wrote: “Since yesterday we no longer heat, but do not think that it is warm. Now the weather here is also ‘forbidden'”.

Adele Halberstam now wrote of many people who “moved out,” “had to leave,” “started an involuntary journey,” or were “picked up,” which always meant the same thing, deported. They lived in this fear since the beginning of 1942, because since January hundreds were sent to the so-called Arbeitseinsatz in KZ Westerbork and from there to Germany. In May 1942, there were already about 3,200 detainees in such labor camps.

While the names Westerbork or Drente had hardly been mentioned until the spring of 1942, Adele and Wilhelm Halberstams wrote for the first time in a letter dated April 26, 1942, that people were now being taken there in “quite large numbers.” Around this time, about 1,100, mostly refugees from Germany, had already been transported to the camp. Then, at the end of April 1942, through the mediation of the “Jewish Council,” as they called it, the Halberstams received “Drenter lodgers”: passengers from the refugee ship “St. Louis,” sent back from Cuba in 1939, who had been interned there since the camp was established. After two and a half years of stay, which they had already completed, they were able to report in great detail about their “terrible existence” in Drente.

NEWS OF SOMETHING “THAT NEVER, EVER HAPPENED ANYWHERE”.

At the end of April 1942, the yellow “Jewish star” was also introduced in the Netherlands. “I had my hands full,” Adele wrote on May 1, “since I had to sew on a few yellow stars for each of us.” Since May 2, the “Jewish Star” had to be worn clearly visible on the left side of the garment at chest height. The “Jewish Council” had tried in vain to protest against the measure, and although demonstrations of solidarity and protest on the part of the Dutch did not fail to materialize, the Higher SS and Police Leader Rauter and the head of the Central Office for Jewish Emigration, SS-Hauptsturmführer Aus der Fünten, were able to chalk up the action as a success. The surprised chairmen of the “Jewish Council” were provided with 569,355 stars.

It was clear to Adele and Wilhelm that a new chapter in their struggle for survival had begun. Their repeated references to rumors that sounded “mostly so stupid and unbelievable” that it was better to refrain from spreading them made this clear (Wilhelm Halberstam, June 1, 1942)- Similarly, this resonates in Etty Hillesum’s diaries. The young woman wrote down the following sentences on May 18, 1942: “The threat from outside is constantly increasing, the terror grows with every day.” And on May 31, 1942: “The little atrocities are piling up more and more. (…) I know of persecution and oppression, of arbitrariness and impotent hatred, and of much sadism.” (12)

The following day, June 1, 1942, Wilhelm Halberstam was also back at his desk. He could not describe the situation to the “beloved children” as directly as Etty Hillesum. But he found a paraphrase that could hardly be more apt: For “ship’s mail” was suitable, he wrote, “according to a poet’s phrase, news about something “that has never, ever gone anywhere”. Whether the recipients in Chile could interpret this sentence as Etty Hillesum did back then and we do today is doubtful. Was “nie und nimmer nirgends begeben” already a hint, a cipher for Auschwitz?

In the same days, the freedom of movement of the Jewish population in public was almost completely restricted. Since June 1942, Jews were no longer allowed to use bicycles, they were forbidden to ride public transportation and to use public telephones, they were allowed to shop only between 3 and 5 p.m., and they had to stay at home from 8 p.m. in the evening until 6 a.m. in the morning. Etty Hillesum also noted that: “At any moment you can be sent to a barrack in Drenthe and there are boards on the greengrocer’s stores: forbidden to Jews.”(13)

Already on June 29, 1942, she recorded in her diary, “I know what else can await us.” Her parents were already out of walking distance in Amsterdam. She still knew where they were, but also “that a time is coming when I will not know where they are, only that they have been deported and will perish miserably. (…) According to the latest news, all Jews from Holland are to be deported, via Drenthe to Poland.” The English station had reported “that since last year 700,000 Jews have perished in Germany and in the occupied territories. (…) in Poland the killing seems to be in full swing.”(14) Four days later, on July 3, 1942: “It is a matter of our downfall and annihilation, one should have no illusions about that.”(15)

THE LAST STAGE IN THE STRUGGLE FOR MAN’S RIGHTS

By now we know that in June 1942 the period of forced deportation began for the Jews in Amsterdam. The Dutch quota for Auschwitz was 40,000 Jews, the deportation chief in the Reich Security Main Office, Adolf Eichmann had just informed the Foreign Office. On June 26, 1942, the “Jewish Council” received the first order that a “police labor deployment” of men and women between the ages of 16 and 40 would take place. The “Joodse Raad” was to ensure the registration of those concerned and to prepare the registration for deportation with a form to be sent by mail. Those called up then had to report to the “Central Office for Jewish Emigration”.

As early as July 1, 1942, on the order of Seyß-Inquart to the commander of the Security Police and the SD, Wilhelm Harster, the Westerbork camp was converted into a “police transit camp”. From then on, barbed wire and seven towers served as guards. Since the first calls for so-called “labor deployment in the East” of July 5 and 12, which went mainly to German Jews, were not heeded, raids took place on July 14 in the Jewish quarter and in the south of Amsterdam – i.e. directly at the Halberstams – and 540 Jews were arrested. They were used as leverage against the 4,000 affected who had been called for deportation.

“Tonight the first transport has to turn itself in,” Wilhelm Halberstam wrote on July 14, 1942. Of the 1,400 Jews called up, 962 were deported to Westerbork, among them the children of a family that was friends with the Halberstams. There they were reloaded into freight cars at the Hooghalen train station on the morning of July 15. It was the first of a total of 100 transports from Westerbork, which from then on (until September 1944) were dispatched week after week, supposedly for “work in the East”.

As early as the night of July 15 to 16, 1942, the second train left Amsterdam Central Station, with which Hertha Oppenheimer, the Halberstams’ maid, was also deported. The freight car into which she and the other prisoners had to change in Hooghalen was coupled on the way to the first transport from Westerbork. And so, crammed in and almost dying of thirst, the first 2,000 Jews from the Netherlands arrived at Auschwitz on July 17, 1942. Today we know that 449 people from this “transport” were immediately murdered in the gas chamber. The spectators probably included Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, who was in Auschwitz for the second time on July 17 and 18, 1942, to inspect the camp complex.

Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam’s apartment was directly opposite the buildings of the so-called “Expo”, the exposition of the “Jewish Council”. Only a few hundred meters away was the assembly point for the “Transports to the East”, at the same time the seat of the “Central Office for Jewish Emigration”: two places where life and death had to be decided. At the “Expo”, the persecuted received the coveted stamps that allowed them to remain in the Netherlands “until further notice”, provided that the “Central Office” had certified their deferral from the “work assignment”. Those who succeeded in obtaining a function at the “Jewish Council” could hope to be temporarily deferred from the deportations.

Etty Hillesum, who initially resisted but finally accepted a position with the “Cultural Department” on July 15, 1942, wrote about the “bogus positions” at the “Jewish Council” that there was “quite a bit of nepotism” there. The “bitterness against this strange placement office” was growing from day to day: “And besides: one’s turn comes only a little later after all.” (16) She had seen through the infamous practice of her persecutors, who turned victims into perpetrators. “It can never be repaired,” she wrote in her diary on July 28, 1942, “that a small part of the Jews helps to deport the overwhelming majority.”(17) What Etty Hillesum, who was deported to Westerbork in August 1942, recorded here was also experienced by the Halberstams living not far away. (18)

Among other things, they reported on the keyword “labor service” about two gentlemen who spent the night with them. They had arrived in Amsterdam “with a transport of released mixed couples” from Drente (Wilhelm Halberstam, July 14, 1942). The largest group of those initially deferred included the functionaries of the “Jewish Council” itself and their families, along with doctors, pharmacists, barbers, and shopkeepers who had to provide for the community. Albert Halberstam, who was called up for “labor service” on August 11, 1942, was also able to obtain restitution with the help of connections. In all, the “Central Office” ordered exemptions in over 32,6000 cases by December 1942, based on a steadily refined stamp system. Whereby, as Etty Hillesum wrote, “exemption” always meant only temporal postponement of deportation.

All this the Halberstams had to witness. Thousands of Jews called up for “deportation to the East”, who had to present themselves at the “Expo”; thousands who tried to get a deferment or a saving stamp. Until the collection center became too small and got an extension in October 1942 in the so-called “Joodse”, formerly “Hollands Schouwburg”, a formerly well-known theater.

HUMAN DUTY

In the months beginning in July 1942, raid followed raid, always following the same pattern. Those rounded up were taken hostage until the number set for each transport was reached. Jewish families who hid with acquaintances also put them in great danger. Nevertheless, at the request of the “Jewish Council,” the Halberstams often took in people who were left at the collection point during nighttime actions. Adele wrote about this on September 10, 1942: “Across from us is the office of the Joodsche Raad, to which those who are released by the nearby German authority return (…). This lasts approximately from 12 – 2 o’clock in the morning. Those concerned are not allowed back on the street until 6 o’clock. Albert has made our apartment available for the stay of those concerned, which is really human duty.” Over two hundred people were thus accommodated in their small apartment for nightly quartering in September alone.

As it was stated in a report of the Higher SS and Police Leader Rauter to Himmler at the end of September 1942, 20,000 Jews from the Netherlands had been “marched to Auschwitz” by then. On October 18, Jewry would be declared outlawed throughout the country, and finally a large-scale operation by the police, the Dutch Nazi party, and the Wehrmacht would take place.

The Halberstams heard nothing more about the people who were sent to Westerbork and “onward”. Did they know what the name Auschwitz meant? Did they know more than the “Joodse Raad,” which first became aware of “a death in Auswitz” (sic!) at a meeting on September 18, 1942.(19) In “Auswitz”? As late as August 1942, members of the Council spent five days searching the maps for a place called Birkenau. By then, 15,763 Jews had been deported from the Netherlands to Auschwitz; only of 52 had a sign of life arrived in Amsterdam: a postcard from “Birkenau.” Neither in Etty Hillesum’s diary nor in the letters of the Halberstams does the name Auschwitz or even Birkenau appear. In Anne Frank’s diary, in October 1942, it states:

“The Jewish camp (…) Westerbork must be horrible. (…) If it is already so bad here in Holland, how terrible will it be there in the distance, where they are sent? The English radio reports of gas chambers…”(20)

It seems almost inconceivable that in the midst of these deportation events, Wilhelm Halberstam still had a bilateral cataract operation performed in the Jewish hospital in October 1942. Just now, in November 1942, the letter contact with Chile broke off. From January 1943, only Red Cross messages arrived in Santiago: pre-printed forms that arrived with great delay.

One of these “telegrams” read, “Here since June 20 (1943).” Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam had been deported on one of the terrible transports recorded by the chronicler of the Westerbork concentration camp, Philip Mechanicus. It was a Sunday, this 20th of June 1943, and at the “end of a glorious summer day,” Mechanicus wrote, “one of the last waves of Jews washed in from Amsterdam.” The following day, Mechanicus returned to this transport once again:

“Today, early in the morning, thousands of suitcases, sacks and bundles arrived, which the Jews had taken from their homes (…).In densely packed squads they have been herded into the barracks: Three, four, sometimes five people in two beds, along with their luggage. (…) Up to eleven hundred people in one barrack without the slightest room to move. (…) Like ants, they run over each other, past each other, like small, insignificant ants.”(21)

“Kamp Westerbork, B 84” (Barrack 84), was the last address of the Halberstams, who could no longer transmit much to Chile, including a message of transports on September 29 with which their son Albert arrived in Westerbork; another under the date of October 5, 1943, from Adele, that her beloved Wilhelm had died the day before as a result of a heart attack. “Namelessly sad” Adele wrote about his last days, about a pneumonia still last survived in the sick barracks. Nothing else from the camp.

We know from Mechanicus that things were terrible there at the same time. Already on September 4, 1943, he had noted in his diary that the fate of Westerbork was “sealed,” that the decision had been made and announced:

“(…) to dissolve the camp and send the Jews to the East, to Auschwitz, to Theresienstadt and Central Germany. (…) The camp is overwhelmed by the decision (…) resembles a beehive: everyone goes to everyone to discuss the case. Anger comes up against the English and Americans who land in Calabria, but not in Holland, and therefore are far from being in Westerbork. (…) The Jews spur each other on to finally use up the supplies and to take vitamins in order to arrive as strong as possible in Poland, Germany or elsewhere (…). Sensible Jews say: let them send us to Poland, we will arrive there in good shape and will help our weakened brothers and sisters.” (22)

The persecuted and the fugitives fought for their survival, they did not want to give up. Only in retrospect can the Westerbork chronicler’s closing remark be interpreted as a reference to the planned genocide:

“All Jews go one and the same way. They are removed from Dutch territory, without exception, without regard to the person, and are deported to the East.”(23)

Every Monday, the transport train, “the mangy animal,” came crawling in – with terrible regularity. Now, however (according to the entries of October 3 and 4, 1943), one doubted whether the “slave transport” would even get there in view of the advance of the Red Army. “Rumor has it that the Germans have already been busy for a few weeks withdrawing the Jews in the east behind the front to the large Auschwitz camp.”(24)

“THE PURPOSE OF LIFE IS MISSING” – DEATH IN AUSCHWITZ

The rumors were just buzzing around the Westerbork camp and they only made it harder for Adele Halberstam, who was by now 71 and suffering bitterly from her husband’s death. “I function like an automaton, the purpose of life is missing,” she telegraphed to the “beloved children” on October 31, 1943. Only now had she given up. It was her last message. Fourteen days later, her name was also on one of the lists read out in the barracks the night before the arrival of the “mangy animal,” “unblocked, free for transport,” as it was called in camp parlance. The historian Jacques Presser called it the “night of calamity,” always referring to the night hours from Sunday to Monday, when the “big list” was read out publicly in the registration hut, often until after midnight. During this “transport night”, it was then necessary to pack and to load and dispatch the train, which drove into the middle of the camp, in the morning hours.

On Tuesday, November 16, 1943, Adele Halberstam, her son Albert, and 993 other camp inmates were sent “on transport” to Auschwitz. Philip Mechanicus also recorded this day in his diary:

“Transport of over a thousand people: Punished, unstamped, rejected applicants for Palestine, among them many young men, hospital staff, sick people. (…). A ‘normal’ transport. The younger ones among the exiles accepted the journey singing. One can see in the camp that there are now a thousand people less. Now there are about eight and a half thousand people left. How much longer?”

The transport arrived at Auschwitz on November 17, 1943, and 531 people were killed immediately in the gas chamber. Among them was Adele Halberstam. Her son Albert survived until March 31, 1944.

ADELE AND WILHELM HALBERSTAM’S LEGACY

This is the story of the Halberstams, whose children and grandchildren managed to escape to Chile, where today, as the last survivor of the first generation of refugees, their granddaughter Lore Hepner lives, with her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Where did the two old people get the courage and what gave them the strength not to give up and also to give their children optimism so as not to make it difficult for them to make a new start in Chile? Adele and Wilhelm did not complain, they did not whine, they fought for every day of their lives, which were becoming more and more cramped and oppressed. We learn a lot from their letters about the German occupation of the Netherlands, how the danger became greater and greater, the living space smaller and smaller, and what it means not to be humiliated.

The letter messages traveling from Amsterdam to Santiago hinted at much that was just happening or about to happen in the occupied Netherlands. The letters are also proof that the isolation wanted by the rulers of the “Third Reich” never existed and that whoever wanted to know could do so.

How many more such letters have there been, cries of distress? Why was there not more solidarity? Because the Halberstams themselves proved that this was possible in the hour of greatest need by taking in numerous persecuted people from the street in their cramped apartment, despite the dangers involved. They gave them a roof over their heads, food to eat and a place to sleep.

Adele and Wilhelm Halberstam’s legacy to us is that anyone who wants to can help, even under extreme conditions. Accepting this legacy makes a big difference to the claim that “one” could not do anything against the superiority of the persecutors and could not resist. It is a legacy that obliges active resistance when human dignity is violated.

It was the love for their children and grandchildren, the desire to join them in Chile and to turn their backs on Europe and all its horrors that made the Halberstams not give up. This hope and the desire to take their son Albert with them kept the two old people alive. However, the question that Adele’s and Wilhelm’s granddaughter Lore Hepner kept asking herself, “Whose hand was it that protected us while my grandparents were killed?”(25), will probably never be fully answered in the end.

Dr. Irmtrud Wojak

Notes

(1) Wilhelm Halberstam, August 18, 1941. All quoted letters are reprinted in: Wojak and Hepner (1995).

(2) Friedländer (1998). S. Friedländer proved how much such letters say in his books and also in his speech on the occasion of the awarding of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade on October 14, 2007, in which he read from the last letters of his parents who were murdered in Auschwitz. Friedländer, Saul (2007).

(3) The Diary of Anne Frank (1957); Hillesum (1985); Mechanicus, (1993).

(4) The Diary of Anne Frank (1957), pp. 11 f. (June 20, 1941)

(5) Hillesum, p. 166.

(6) Hepner (1995), pp. 47 ff.

(7) On Chilean immigration policy, see Wojak (1994).

(8) Gies (1993), p. 29.

(9) Wilhelm Halberstam, May 15, 1939. On June 25, 1939, he wrote that “our love for Amsterdam seems to be so deeply locked in our hearts that we don’t even notice it. […] Among the many thousands one meets when one comes into the streets, no one wears a face known even by sight. This does not increase the interest that the capital is able to extract from us”.

(10) Romijn (1995), p. 316.

(11) Adele Halberstam, May 18, 1940; see also this, June 22, 1940: “I repeat, dear Heinrich, as far as your time permits, to keep trying for a visa for us.”

(12) Hillesum, p. 104.

(13) Ibid, p. 111.

(14) Ibid, p. 120 f.

(15) Ibid, p. 123.

(16) Ibid, p. 149.

(17) Ibid, p. 167.

(18) Ibid, p. 169.

(19) Friedländer (1998), p. 437.

(20) The Diary of Anne Frank, p. 39 f.

(21) Mechanicus, p. 65 (June 21, 1943).

(22) Ibid, p. 182 ff.

(23) Ibid, p. 183.

(24) Ibid, p. 234 f.

(25) Hepner (1995), p. 54.

Bibliography

The Diary of Anne Frank (1957). June 12, 1942-August 1, 1944. 454th-503rd thousand. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer TB (orig. 1955).

Friedländer, Saul (1998). The Third Reich and the Jews. Vol. 1: The years of persecution 1933-1939. Munich: C.H. Beck-Verlag.

Friedländer, Saul (2007). “Listening to the Cries of the Victims,” in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, October 15, 2007.

Gies, Miep (1993). My Time with Anne Frank. In collaboration with Alison Leslie Gold. Munich: Heyne (Dt. orig. 1987).

Hepner, Lore (1995). “In Memory of My Grandparents,” in Wojak, Irmtrud and Hepner, Lore (eds.). “Beloved Children…” Letters from the Amsterdam Exile to the New World 1939-1943. 1st ed. Essen: Klartext Verlag, pp. 47-54.

Hillesum, Etty (1998). The thinking heart. The diaries of Etty Hillesum 1941-1943. Edited and introduced by J. G. Gaarlandt. Translated from the Dutch by Maria Csollány. 15th edition. Reinbek bei Hamburg: rororo.

Mechanicus, Philip (1993). In the depot. Diary from Westerbork. Translated from the Dutch by Jürgen Hillner. 1st ed. Berlin: Edition Tiamat.

Romijn, Peter (1995). “De oorlog (1940-1945),” in Geschiedenis van de Joden in Nederland. Ed. by J.C.H. Blom et al. Amsterdam: Uitgeverj Balans, pp. 313-347.

Wojak, Irmtrud (1994). Exile in Chile. German-Jewish and political emigration during National Socialism 1933-1945. Berlin: Metropol.

Wojak, Irmtrud and Hepner, Lore (eds.) (1995). “Beloved Children…” Letters from the Amsterdam Exile to the New World 1939-1943. 1st ed. Essen: Klartext Verlag.