"We honour Dawit Isaak for his resistance, courage and commitment to freedom of expression. Defending fundamental freedoms requires courage and determination."

Guillermo Cano, World Press Freedom JuryRead more:

Nationality at birth: Eritrea

Place of the fight for human rights: Eritrea

| Area | Type | From | To | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profession, Activities | Journalist | |||

| Profession, Activities | Author |

Leitmotif

Journalist and poet defending fudamental rights

Journalist, poet and playwright Dawit Isaak was arrested by police in Eirtrea on September 23, 2001, along with a large number of other journalists and leading representatives of the Eritrean government. Isaak and his colleagues were arrested following the closure of eight newspapers by the Eritrean state authorities on September 18, 2001. Dawit Isaak has now been in detention for over seventeen years, without official charge or trial. He has no contact with the outside world and neither his family nor his lawyers know his whereabouts or physical condition.

Prizes, Awards

2003 Freedom of the Press Prize, Reporters Without Borders

2006 The Anna Politkovskaya Award

2009 The Tucholsky Prize, Swedish PEN; Norwegian Freedom of Expression Prize

2010 Golden Pen of Freedom, the annual press freedom prize of the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers.

2017 UNESCO Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize

Nominated for the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought

Honorary Member Swedish Writers’ Union

Honorary Member PEN America, PEN Canada, PEN Finland

Literature (literature, films, websites etc.)

Documentaries:

2011 “Fången – Dawit Isaak och Tystnaden (“Imprisoned – Dawit Isaak and the Silence”), Maria Magnusson and Gellert Tamas

http://tamas.se/dokumentarer/fangen/

Music videos:

2009 Dawit Isaak, Mefic, https://myspace.com/mefic/music/song/dawit-isaak-50672457-54605891

2014 Fågelsång – Bird Song , with Alexander Skarsgard and others, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gyunL8xYORg by www.freedawit.com

2016 Together for Dawit, https://open.spotify.com/artist/25dZpjMFlAXCznruTjI3Sk

Read more about Dawit Issak and Eritrea:

www.freedawit.com

www.article19.org

www.cpj.org

www.danconnell.net

www.onedayseyoum.org

www.pen-international.org

www.peneritrea.com

www.asmarino. com

www.ohchr.org

Tenkam Arat (Troublesome bed), Theatre Play.

Zeytehatsbet Mendil (Unwashed handkerchief).

Bana: The Affair of Mussie and Mana (ባና፤ ታሪኽ ፍቕሪ–ሙሴን ማናን), 1988.

“The Thirty thousands” (“እተን ሰላሳ ሽሕ”) , short story, 1993.

Dilly Dally, Theatre Play, 1997.

Hopp: historien om Moses och Mannas kärlek & andra texter. Editors: Björn Tunbäck och Swante Weyler: Stockholm: Weyler, 2011.

Dawit och friheten: om den svenske samvetsfången och Eritreas inställda demokratisering. Editors: Johan Karlsson & Rickard Sjöberg, Stockholm: Silc Förlag, 2004.

Tystade röster (Quieted Voices). Anthology of texts by several writers and journalists in detention. Includes an article written by Dawit for Setit, pleading with the government to reply not only to inquiries from foreign media but to also answer questions from the domestic Eritrean press.

The Library of Congress in the U.S. holds a collection of nearly all of publications by Setit, 1997-2001, www.loc.gov.

INTRODUCTION

Journalist and poet defending fudamental rights: Journalist, poet and playwright Dawit Isaak was arrested by police in Eirtrea on September 23, 2001, along with a large number of other journalists and leading representatives of the Eritrean government. Isaak and his colleagues were arrested following the closure of eight newspapers by the Eritrean state authorities on September 18, 2001. Dawit Isaak has now been in detention for over seventeen years, without official charge or trial. He has no contact with the outside world and neither his family nor his lawyers know his whereabouts or physical condition.

THE STORY

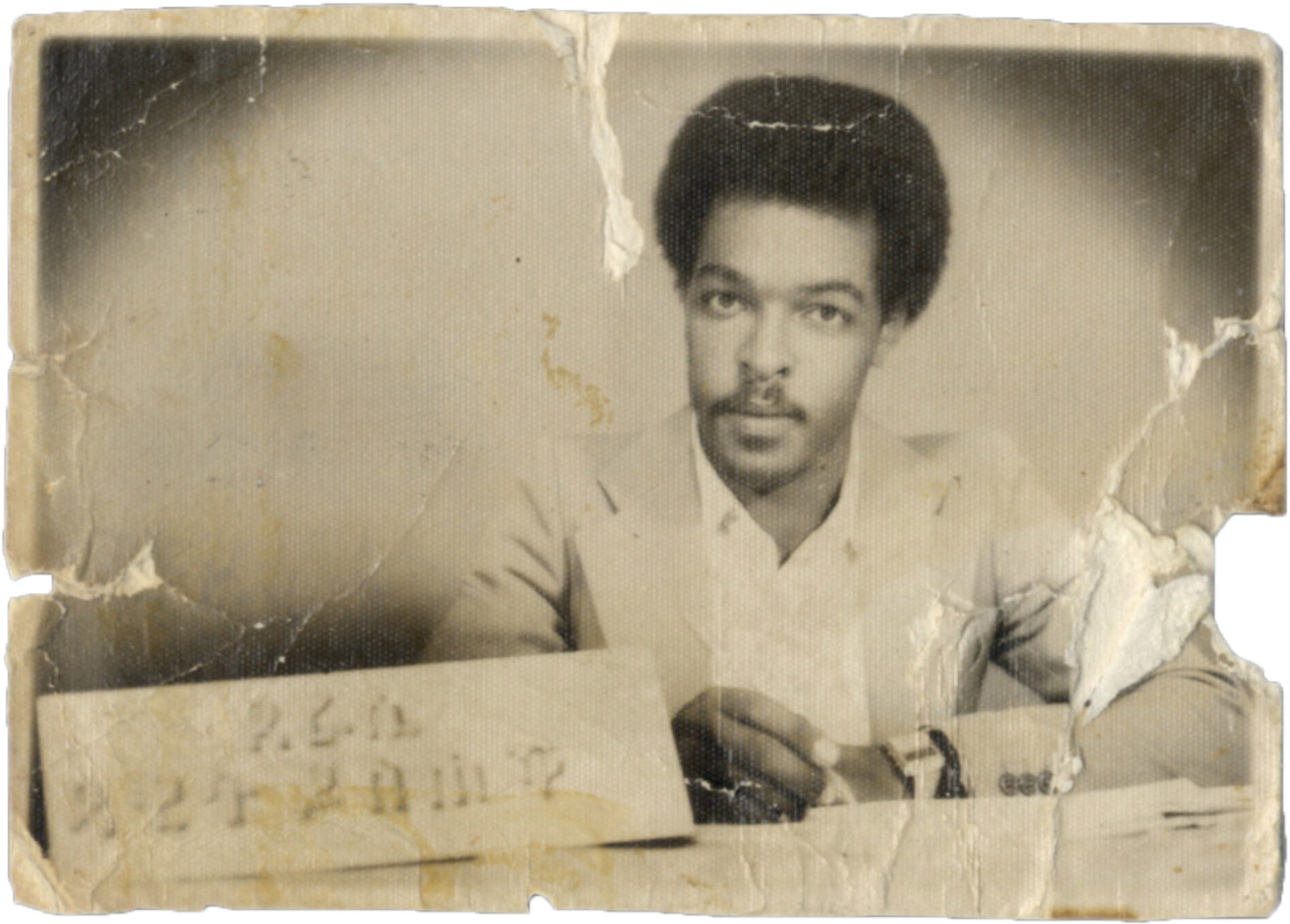

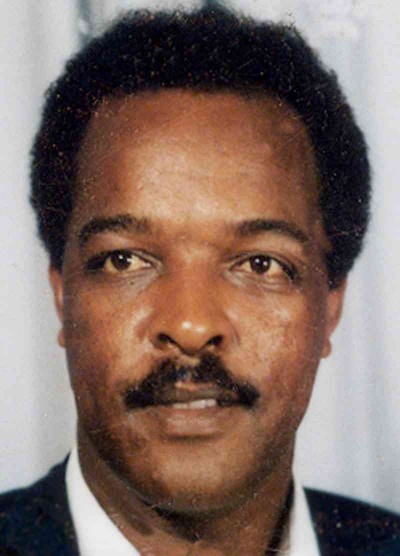

Dawit Isaak

Journalist and poet definding fundamental rights

Journalist, poet and playwright Dawit Isaak, who holds both Eritrean and Swedish citizenship, was apprehended by Eritrean police forces on September 23, 2001. According to news reports at the time, Dawit and other journalists were allegedly arrested for avoiding Eritrea’s compulsory national [military] service. The detentions came in the wake of the closing down of eight newspapers by Eritrean state authorities on September 18, 2001. These included the weeklies Meqaleh, Setit, Tsigenay, Zemen, Wintana, and Admas. Dawit Isaak was a co-owner and contributing writer of Setit (ሰቲት), Eritrea’s first independent newspaper, named after a mighty river in Eastern Eritrea. In early 2001, Setit had published an open letter from the “G-15”, a group of Eritrean politicians and government officials who had sharply criticized the growing erosion of civil liberties in Eritrea, under President Isaias Afewerki. Except for one brief interval in 2005, Dawit Isaak has been imprisoned for seventeen years without charge or trial, with no contact to the outside world. Neither his family nor his lawyers know of his current whereabouts or his physical condition. In March 2017, Dawit Isaak was awarded the UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize. In its unanimous decision, the jury cited its wish to recognize Dawit “for his courage, resistance and commitment to freedom of expression.” He was also shortlisted for the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought (European Union).

Dawit Isaak was born on October 28, 1964 in Eritrea which at the time was part of Ethiopia. He and his five siblings grew up in relative comfort in the capital city in Asmara, where his parents managed an Italian deli. From a very young age, Dawit showed an affinity for writing. His younger brother Esayas recalls that Dawit literally wrote everywhere – at the breakfast table, before school; in his spare time, when other kids were playing; at night, in his bed. While still in elementary school, he began to author and stage theatre plays. As a young adult he published two novels in his native language of Tigrinya, winning several prizes and bringing him to national attention. But at the time, Eritrea found itself embroiled in a brutal war for independence (1961-1991). In 1985, Dawit fled the violence, finding refuge in Sweden. He soon managed to find employment as a janitor at a church in Gothenburg and in 1992 he obtained Swedish citizenship.

During his time in Sweden, Dawit maintained an active role as a member of the Eritrean exile community. Esayas Isaak recalls that Dawit was always more keenly interested in culture than in politics, urging his younger sibling to remember “your language, your country, your roots”. To that end, Dawit made sure that Esayas kept up his regular lessons in Tigrinya.

For Dawit, more than anything else, the arts hold the key to affecting social change.[3] When Eritrea declared independence in 1993, Dawit decides to return to his home country to actively help shape its democratic and cultural development. He also marries and starts a family. Soon he and his wife Sofia become parents of three children – the twins Bethlehem and Yorun and their younger sister Danait. [4] At this time, Dawit returns to his first love, the theatre, focusing on working with young children at the Shewit Children’s Theatre and the acrobat group Circus Eritrea. Both organizations he co-founded with Isaias Tsegai and his friend and fellow journalist Fesshaye Yohannes who is believed to have died in prison in 2007.

Dawit gains national prominence with his short story “The Thirtythousands” (“እተን ሰላሳ ሽሕ”) which was serialized on Eritrean Radio and widely discussed. [5] It tells the story of a mean and tight-fisted barber who stores a large amount of cash in his barber-chair only to find his money worthless, due to a change in currency, when he tries to collect it years later.

Since 1993, Eritrea is governed by Isaias Afewerki, a former military commander and political commissar of the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF, later the Eritrean Peoples’ Liberation Front, EPLF) which led the battle for independence. In 1996, the Eritrean government issued the so-called Press Proclamation Law which allows for private ownership of print media. A few journalists decide to seize the opportunity and launch Eritrea’s first independent newspaper, Setit. Dawit soon joins the publication as contributing writer and later, as investor and co-owner. To Dawit, all news matters, from big issues like war and international relations to local conflicts. He quickly builds a reputation as a skilled interviewer who is able to put his subjects at ease. Dawit becomes known in particular for his insightful portrays of Eritrean writers and artists. His personal motto is simple and direct: “If you have the opportunity to write, do it.” [6]

Like his fellow countrymen, he is eager for his country to achieve economic development, but his main interest is in promoting social justice. Dawit’s colleague and co-founder of Setit, Aaron Berhane, considers Dawit one of the most gifted journalists he has ever met, able to present even the most complex and sensitive issues in easily accessible terms. His topics include border disputes, lack of clean water and literature. Dawit’s friends remember and admire him for his quiet authority and calm, as well as his careful argumentation, even during the most tense discussions.

Afewerki’s rule, however, turns more and more autocratic. Prompted by the increasingly difficult conditions in Eritrea, Dawit decides to move his family to Gothenburg in 2000. He returns to Eritrea right away the following year. Dawit uses his platform as a journalist to press for more openness and transparency in public affairs. In an article published in Setit, he pleads with government leaders to reply not only to foreign media inquiries, but to also pay attention to the questions posed by the Eritrean press.

In early 2001, a group of prominent Eritrean politicians and government ministers begins to express public criticism and concern about how President Afewerki was running the country. This group becomes later known simply as the “G-15”. In a series of public letters, they demand that elections be held as promised and for the proposed constitution to be implemented. In spite of threats and increasing risks to their own safety, Dawit and his colleagues regularly report on these demands in Setit.

Dawit Isaak is personally acquainted with Eritrea’s President and has met him on several occasions. [7/8] But this does not protect him from becoming a target. On 23 September 2001 there is a knock on the door of the Isaak home. Outside are two security officers who have come to arrest Dawit. He invites them inside and even offers them a cup of tea before they take him away. Dawit and most of the G-15 are imprisoned in an apparent attempt by President Afewerki to suppress freedom of expression and debate in Eritrea. [9]

In October 2001, Eritrean government officials deny that a politically motivated crackdown is taking place, claiming instead that Dawit and other journalists had merely been sent to carry out their mandatory national military service. They also state that the closures and mass arrests were necessary for the sake of national unity and were carried out because of the newspapers’ failure to comply with laws covering media licenses. All those detained have their bank accounts frozen and their personal assets confiscated.

Since 23 September 2001 Dawit has been imprisoned without being the subject to any legal proceedings or formal sentencing. No evidence has been presented to substantiate his arrest, no official charges have been lodged after sixteen years and he has not been granted a trial, in breach of both national and international law.

When Dawit was arrested he was – as are all journalists – exercising his basic [human] right according to Article 19 of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights , “the right to freedom of opinion and expression.” Eritrea formally supports the Declaration. Eritrea also has repeatedly been urged to comply with current international law as stated in the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

In November 2001, the Swedish Consul in Asmara was permitted a brief meeting with Dawit in jail. In April 2002, it was reported that Dawit had been hospitalized and that he was suffering from non-disclosed injuries sustained in prison as well as diabetes. Two years later, in April 2004 news emerged Dawit and other journalists were reportedly being held in secret security sections of the 2nd and 6th police stations in Asmara.

In November 2005, Dawit was suddenly released from custody and was allowed to call his family and friends in Sweden. He was returned to prison only two days later, with no explanation. Since then, Dawit has allegedly been moved to various prisons around the country. As of December 2008, Dawit was supposedly being held at a maximum-security prison in Embatkala, 35km northeast of Asmara. Prison conditions in Eritrea are extremely severe. Summer temperatures regularly exceed 45°C (113°F), with poor sanitation and virtually no medical care. According to Amnesty International and other international human rights organizations prisoners are regularly forced to undertake “painful and degrading activities, and were tied with ropes in painful positions for long periods.”

In January 2009 Dawit was apparently transferred from prison to an Air Force hospital in Asmara as a result of serious illness but was later returned to prison. In January 2010 new witnesses claimed that Dawit was being kept in solitary confinement, in a tiny cell with no windows and was in very poor physical and mental health. He and the other inmates are reputedly not allowed any contact with each other or the outside world. The latest reports indicate that Dawit is being held at EiraEiro prison camp, 10 miles north of Asmara. [10]

In mid-April 2010, the Swedish Member of the European Parliament Eva-Britt Svensson stated that the Eritrean ambassador in Brussels, Girma Asmerom Tesfay, had told her in a meeting that Dawit was to be formally charged with a crime and taken to court. However, this was swiftly denied by the Eritrean Embassy in Brussels.

There are serious concerns about Dawit’s state of health resulting from the conditions under which he has been detained for 16 years now. Many of Dawit’s colleagues and most of the G-15 have reportedly died while in prison.

Since 2001, the Eritrean leadership has summarily ignored all outside attempts to obtain information about Dawit Isaak. In 2009, President Afewerki commented briefly on Dawit’s detention: ”We will not have any trial and we will not free him. We know how to handle his kind.” So far, the severe sanctions regime first imposed by the U.N. in 2009 has not had yielded any change in this attitude. Neither has the new policy of ‘engagement’ of Eritrea pursued by the European Union in recent years.

In 2011, his all-volunteer legal team (attorneys Jesús Alcalá, Prisca Orsonneau and Percy Bratt) filed a petition of habeas corpus with the Eritrean High Court.

Habeas corpus is a formal legal request that imposes a duty on Eritrean officials to immediately present Dawit Isaak before a court of law. So far, Eritrea has simply ignored the filing. Eritrea has in earlier cases before the African Commission stated that they respect the principle of habeas corpus. However, in this case the High Court did not even want to admit it had received the writ. In January 2012, yet another copy of the petition was handed over to Eritrean authorities by the European Union’s representation in Asmara, to be forwarded to the Court. Still, the Eritrean High Court would not acknowledge receiving the filing for habeas corpus.

Given Eritrea’s lack of response, Dawit’s lawyers in the autumn of 2012 formally filed a communication with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) to officially request Eritrea to set Dawit free. In October 2013 Eritrea answered the Commission that they do not find all legal measures exhausted in the case in Eritrea. Nevertheless, the Commission decided to proceed with the case. In 2016, the Commission decided not to retry Dawit’s case, arguing that the matter had been addressed as part of an earlier filing before the Commission in 2003, brought by the Human Rights Group Article 19. However, the Commission did in the strongest terms condemn the Eritrean government’s handling of Dawit Isaak’s detention and demanding his immediate release. The Commission also called for Eritrea to ensure that Dawit receive legal counsel and be allowed contact with his family. Specifically, the Commission found that Eritrea violated a number of provisions of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, including [11]

· the right to a fair trial (Article 7.1)

· the right to obtain legal counsel (Articlel 7.1 c)

· the provision against torture, stating that total isolation of a prisoner like Dawit Isaak for prolonged periods of time constitutes torture (Article 5)

· the right to freedom of expression (Article 9)

· the right to life and family. According to the Commission, Eritrea has not only violated Dawit Isaak’s personal rights but also those of his family. (Article 18)

· the fact that all signatory countries have a duty to respect the Charter’s statutes (Article 1)

Eritrea has ranked last in Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index for years. In 2015, the Eritrean government finally released six journalists it had imprisoned since 2009. Unfortunately, Dawit Isaak was not among them. The release is a sign that the Eritrean government may feel vulnerable to international pressure. The International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance guarantees victims of repression and their families the right to truthful information about their ordeal. Still, the Swedish government and the international community has been hesitant to invoke various legal tools to force the Eritrean leadership to finally provide information about Dawit Isaak’s whereabouts and physical condition.

In 2010, Swedish human rights attorney Percy Bratt and his colleague Olle Asplund authored a formal legal opinion which asserted that, based on international law and European Court cases the Swedish government does not only have the right but indeed an obligation to speak on Dawit Isaak’s behalf.

In 2015, Sweden passed legislation that significantly strengthens the country’s commitment to the principle of ‘universal jurisdiction’ – the ability to prosecute crimes against humanity anywhere in the world, irrespective of where these crimes may have been committed. Yet, Swedish prosecutors so far have refused to open a formal investigation of the Eritrean leadership for the crimes of torture and illegal detention committed against Dawit Isaak.

When Dawit’s legal team appealed the decision, Sweden’s Prosecutor General chose not to overturn the original ruling. In a significant departure from the earlier decision he stated, however, that the enforced disappearance of Dawit Isaak and his colleagues meets the standard of “crimes against humanity” and that a formal investigation of the charges against Eritrea’s leadership could and should proceed.

In June 2016 in an interview with Radio France Internationale (RFI), Eritrea’s Foreign Minister Osman Saleh claimed that Dawit Isaak was alive, though no further information has been provided. In the same interview, the foreign minister said that the detained men, including Dawit Isaak, would be tried “when the government decides”.

In March 2017, Dawit Isaak was awarded the UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize. With its unanimous decision, the jury wished to recognize Dawit Isaak “for his courage, resistance and commitment to freedom of expression.” The recommendation was officially endorsed by the UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova.

“Defending fundamental freedoms calls for determination and courage – it calls for fearless advocates,” Bokova wrote. “This is the message we send today with this decision to highlight the work of Dawit Isaak.”

The prospect of a resolution of Dawit Isaak’s case in the near future remains bleak. Even after the settlement of a twenty-year long border dispute with Ethiopia in July 2018, and the subsequent lifting of key U.N. sanctions, President Afewerki shows no sign of relinquishing his power or reinstating Eritrea’s constitution.

Author: Susanne Berger

References

1. Filing on behalf of eleven detained former Eritrean government officials before the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 2002 http://www.achpr.org/communications/decision/250.02/

2. Filing on behalf of 17 detained Eritrean journalists before the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 2003 http://www.achpr.org/communications/decision/275.0 3/

3. Writ of Habeas Corpus for Dawit Isaak, filed in 2011 with the Eritrean High Court in Asmara, Eritrea

4. http://www.peneritrea.com/blog/dear-dawit-happy-birthday

5. http://www.reportrarutangranser.se/nyheter/20170430/fornyat-krav-fran-achpr-att-eritrea-ska-slappa-dawit-isaak

6. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2016/eritrea

7. Eritrea’s prisons https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pt8ST1U4o60

8. EiroEira Prison https://rsf.org/en/news/new-revelations-about-eiraeiro-prison-camp-journalist-seyoum-tsehaye-cell-no-10-block-a01

9. https://rsf.org/en/news/six-eritrean-journalists-released-after-nearly-six-years-prison

10. Kerry Kennedy,”Time to free Swedish Journalist Dawit Isaak”, The Local , 5 May 2015.

https://www.thelocal.se/20150505/time-to-free-swedish-freedom-fighter-dawit-isaak

11. http://en.rfi.fr/africa/20160621-eritrea-foreign-minister-denies-human-rights-abuses-clashes-ethiopia-disappeared-act

12. http://en.unesco.org/courier/july-september-2017/dawit-isaak-symbol-press-freedom-who-must-be-freed

13. Manuel Vergara, ‘The Power of Universal Jurisdiction’, paper presented at the Raoul Wallenberg International Roundtable, Stockholm, 14 September 2017.

14. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/CoIEritrea/Pages/2016ReportCoIEritrea.aspx

15. http://www.thenational.scot/news/14896688.Campaigners_release_song_for_Eritrean_journalist_Dawit_Isaak_marking_his_15th_year_in_prison/

16 .http://www.kingsizemag.se/samhalledebatt/daniel-boyacioglu-moh-denebi-slapper-videon-fagelsang-for-dawit-isaak/

17. Interview with a former Eritrean prison guard , http://hrc-eritrea.org/391/

18. Human Rights in Eritrea http://hrc-eritrea.org/how-the-human-rights-crisis-in-eritrea-reached-this-point/

Partial List of Journalists detained in Eritrea (2000 -2013)

1. Ghebrehiwet Keleta: reporter for ጽጌናይ (Tsigenay: ‘The Pollinator’), arrested in July 2000 before the political crackdown. He has been detained incommunicado without charge since then.

2. Amanuel Asrat: award-winning poet, chief-editor and co-founder of ዘመን (Zemen: ‘Times’), credited with establishing literary clubs in the country. He was been detained incommunicado without charge since September 23, 2001. Amanuel was reported to be alive in Eiraeiro prison camp, according to a former prison guard who fled the country in 2010.

3. Idris Aba’Are: author of two books, freelance journalist, disabled veteran freedom fighter who was serving as director at the Ministry of Labour and Human Welfare at the time of his arrest in October 2001. Rumoured to be held in Eiraeiro, but no information from official or other sources has been made public since his arrest.

4. SeyoumTsehaye: co-founder of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF)’s department of photography during the armed struggle; co-founder and first director of the state-owned national TV station, Eri-Tv; freelance journalist and photographer who was arrested with the political reformist group known as G-15 in September 2001. According to the latest information, Seyoum was being held at Eiraeiro prison camp.

5. Yosuif Mohammed Ali: Tsigenay’s editor-in-chief and co-owner, taken into custody along with other journalists for the independent newspapers on September 23, 2001; reported dead in prison camp in 2006, but his family has not received any official notification.

6. Said Abdelkadir: ኣድማስ (Admas’: ‘The Universe’) chief-editor and owner, an entrepreneur, taken to prison on September 23, 2001. Reported dead in a prison camp according to the limited information available, but this has not been confirmed by the authorities.

7. Medhanie Haile: ቀስተ-ደበና (Keste-debeena’s: ‘Rainbow’) assistant chief-editor and co-founder; a lawyer who was working at the Ministry of Justice at the time of his arrest on September 23, 2001. Reported dead in a prison camp, but this has not been officially confirmed.

8. Dawit Isaak: Swedish-Eritrean journalist, playwright, poet, co-owner of ሰቲት (Setit); taken into custody on the dawn of September 23, 2001; briefly released for few days in 2005, but taken back to an undisclosed location shortly afterwards.

9. Dawit Habtemichael: መቓልሕ (Meqalh’s: ‘Echo’) co-owner, co-founder and assistant chief editor, who was working as a physics teacher in Asmara at the time of his arrest in September 2001. According to a former prison camp guard, he was suffering from schizophrenia and was in a deteriorating health state in 2010; no further information has come to light.

10. Matheos Habteab: Meqalh’s co-founder, co-owner and its chief editor, detained on September 23, 2001. Habteab was a conscript to the Eritrean defense army at the time of his arrest. He is reported to have died in 2010, but this has not been officially confirmed.

11. Temesegen Ghebereyesus: actor; Keste-demena editorial board member and editor of its sports section, taken to prison on September 23, 2001. According to the latest information from the former prison guard, he was reported alive in Eierairo prison camp.

12. Fessaheye Yohannes “Joshua”: poet, playwright, co-founder of Shewit Children’s Theatre and co-owner of Setit; Fessehaye was detained along with other journalists in September 2001. According to leaked information, he is reported to have died in 2006, but this has not been officially confirmed by the Eritrean authorities.

13. Sahle Tseazagab “Wedi-Itay”: a veteran freedom fighter and freelance journalist, first for the state press and then for Zemen. He turned to writing for Zemen when the state-owned newspaper began to censor his forthright articles on Eritrea’s deferred dreams. At the time of his arrest in October 2001, he was serving as director of the civilian affairs branch at the Attorney General’s office and was finalizing his departure to South Africa to pursue his studies. Reporters Without Borders report that Sahle died of poor health in prison, but there has been no official explanation from the Eritrean authorities. He leaves behind two daughters.

14. Saleh Idris “Aljazeeri”: journalist for the state-owned Arabic daily Eritrea alhaditha who was also working for Eritrean State Radio Arabic desk at the time of his arrest in February 2002. In addition to his regular duty at the radio, Saleh regularly wrote articles for the Arabic newspaper. Since then Saleh has been detained in an undisclosed location with no official explanation from the Eritrean authorities.

15. Hamid Mohammed Said “CNN”: Sports journalist for the Arabic language service of Eri-TV. He was arrested on February 15, 2002, reportedly in connection with the political crackdown, but was never brought to court. The Eritrean government has not clarified his whereabouts.

16. Jim’ie Kimeil: Investigative reporter and editor of thesports section for the state-owned Arabic daily newspaper Eritrea alhaditha; veteran freedom fighter whose critical articles were the source of tensions with his employers at the Ministry of Information. He was detained on November 24, 2005 as part of a wave of arrests that included other 13 prominent figures including the famous singer and song writer Idris Mohammed Ali and Taha Mohammed Nur, one of the founders of the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) (who died in detention in 2008). Jim’ie and the others were never charged; their whereabouts remain unknown.

17. Sultanyesus Tsigheyohannes: journalist for the state-owned English language newspaper, Eritrea Profile, arrested in December 2008 in connection to his faith. He was neither charged nor his current location disclosed to his family.

18. Abubeker Abdelawel Abdurahman: published author and dramatist who worked as a freelance reporter for the Ministry of Information in different zones; at one time he was assistant chief-editor of the Tigrinya daily ሓዳስ-ኤርትራ (Haddas Ertra: “The New Eritrea”). He was arrested in February or March 2013 in connection with the January 2013 mutiny; he has never been brought to court and was taken to an undisclosed location.

Source: Pen International www.pen-international.org’

Eritrean Journalists released in 2013

1. Mohammed Said Mohammed

2. Biniam Ghirmay

3. Esmail Abd-el-Kader

4. Araya Defoch

5. Mohammed Dafla

6. Simon Elias

7. Yemane Hagos

Eritrean Journalists released in 2015

1. Bereket Misghina, Radio Bana

2. Yirgalem Fisseha Mebrahtu, Radio Bana

3. Basilios Zemo, Radio Bana

4. Meles Negusse Kiflu, Radio Bana and Radio Zara

5. Girmay Abraham, Radio Dimtsi Hafash

6. Petros Teferi

Source: www.rfs.org https://rsf.org/en/news/six-eritrean-journalists-released-after-nearly-six-years-prison