"A book that wrests universal wisdom from an individual biography."

Denis Scheck, "Tagesspiegel"Read more:

† 29. May 2023 in Miami, Florida

Nationality at birth: Czech

Mundek Buergenthal

* 21. November 1901† 15. January 1945, External Camp Ohrdruf-Nord (KZ Buchenwald)

Gerda Buergenthal, born Silbergleit

* 1912† 1991

Place of the fight for human rights: Ghetto Kielce, KZ Auschwitz, KZ Sachsenhausen

| Area | Type | From | To | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School | Pupil | 1947 | 1951 | Göttingen, Germany |

| Bethany College | Student | 1952 | 1957 | Bethany, West Virginia, USA |

| New York University School of Law | Student | 1957 | 1960 | New York City, NY, USA |

| Harvard University | Student | 1961 | 1962 | Cambridge MA, USA |

| State University of New York | Professor of Law | 1962 | 1975 | Buffalo, NY, USA |

| University of Texas | Professor of International Law | 1975 | 1980 | Austin, Texas, USA |

| Inter-American Court of Human Rights | Judge and President | 1979 | 1991 | San José, Costa Rica |

| American University | Dekan and Professor of International Law | 1980 | 1985 | Washington DC, USA |

| Emory University and Carter Center | Professor of Human Rights and Director | 1985 | 1989 | Atlanta, Georgia, USA |

| George Washington University | Professor of Comparative Law and Jurisprudence | 1989 | 2000 | Washington DC, USA |

| Inter-American Development Bank | Judge | 1989 | 1994 | Washington DC, USA |

| UN Truth Commission for El Salvador | Member | 1992 | 1993 | El Salvador, El Salvador |

| United Nations Human Rights Committee | Member | 1995 | 1999 | (Expert Body) |

| International Court of Justice | Judge | 2000 | 2010 | Den Haag, Niederlande |

| George Washington University Law School | Professor of Law | 2010 | Today | Washington DC, USA |

How did the story become known?

By the autobiography of Thomas Buergenthal.

When did the story become known?

2007

Where did the story become known?

USA, Germany

By whom did the story become known?

By Oral History-Interviews and the autobiography of Thomas Buergenthal

Prizes, Awards

Honorary doctorate from the Law Faculty of Heidelberg (July 1986) and the Law Faculty of the Georg-August-University of Göttingen (April 2007)

Goler T. Butcher Medal (1997) and Manley O. Hudson Medal (2002) of the American Society for International Law

Gruber Justice Prize (2008)

Naming of the Göttingen City Library in honour of T. Buergenthal (2008)

Elie Wiesel Award of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2015)

Olympic Order (2015)

Grand Federal Cross of Merit (2017)

Edith Stein Prize (2019)

Edith-Stein-Preis (2019)

Literature (literature, films, websites etc.)

Interviews

Contemporary Witness Thomas Buergenthal United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (englisch)

Profile Books: The author of A Lucky Child is interviewed by his publisher, Andrew Franklin of Profile Books, about his experiences as a child during the Holocaust, surviving Auschwitz and how this led him to become a human rights lawyer in later life.

Ich spielte gegen Hitler, die SS und die Krematorien. Ich wollte gewinnen. Arno Luik im Gespräch mit Thomas Buergenthal. In: stern. Vol. 14/2007.

Hassen lohnt sich nicht. Philipp Gessler interviews Thomas Buergenthal. In: taz. 12. April 2007

Meine KZ-Nummer ist wie eine Medaille. Interview with Thomas Buergenthal. In: Der Tagesspiegel. 13. May 2007.

Lebensgeschichtliches Interview mit Thomas Buergenthal. In: Quellen zur Geschichte der Menschenrechte. Arbeitskreis Menschenrechte im 20. Jahrhundert, 4. March 2015, retrieved 16. December 2016.

Own works

Non-fiction

Buergenthal, Thomas, Law-making in the International Civil Aviation Organization. Syracuse University Press. 1969. ISBN 978-0815621393.

Sohn, Louis B.; Buergenthal, Thomas (1973). International Protection of Human Rights. Vol. 1. Bobbs-Merrill. ISBN 9780672818738. Vol. 2 ISBN 9780672821875 Vol. 3 ISBN 9780672842276.

Buergenthal, Thomas; Shelton, Dinah (1995). Protecting Human Rights in the Americas: Cases and materials (4th ed.). N.P. Engel. ISBN 978-3883571225.

Kokott, Juliane; Buergenthal, Thomas; Maier, Harold G. (2003). Grundzüge des Völkerrechts (in German) (3rd ed.). UTB Uni-Taschenbücher Verlag. ISBN 978-3825215118.

Buergenthal, Thomas; Thürer, Daniel (2010). Menschenrechte: Ideale, Instrumente, Institutionen (in German). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3832951252.

Buergenthal, Thomas; Shelton, Dinah; Stewart, David; Vazquez, Carlos (2017). International Human Rights in a Nutshell (5th ed.). West Academic Publishing. ISBN 978-1634605984., Thomas, Shelton, Stewart, 4th ed. (2009).

Buergenthal, Thomas; Murphy, Sean D. (2018). Public International Law in a Nutshell (6 ed.). West Academic. ISBN 9781683282396., 5th ed. (2013), 4th ed. (2007).

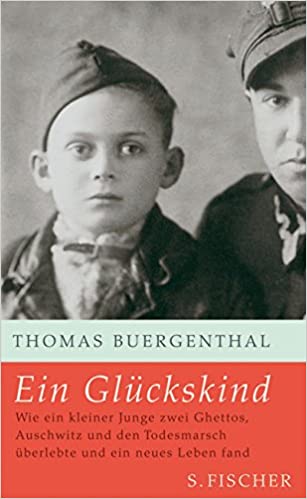

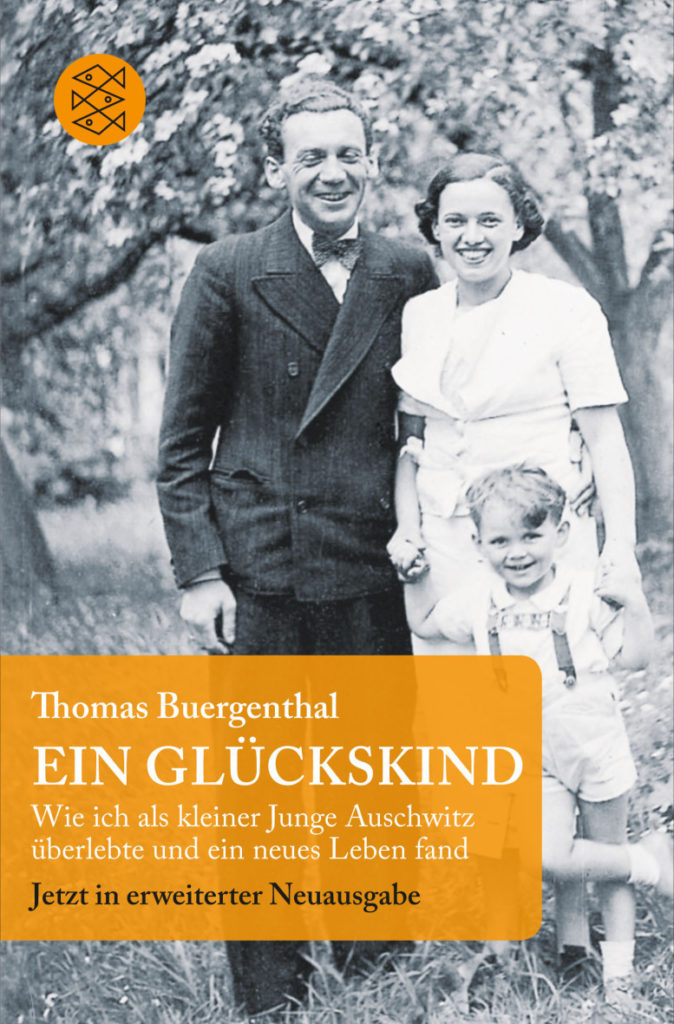

Autobiography

Thomas Buergenthal, A Lucky Child. Little Brown. 2007. ISBN 978-1-61523-720-3.

Thomas Buergenthal, Ein Glückskind. Wie ein kleiner Junge zwei Ghettos, Auschwitz und den Todesmarsch überlebte und ein zweites Leben fand. S. Fischer Verlag: Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-10-009652-4. (Rezensionen bei Zukunft braucht Erinnerung; Wilfried Weinke: Tag für Tag. In: Die Zeit. Nr. 13/2006, S. 45; Soraya Levin: Kindheit im Holocaust. rezensionen.ch, 14. Mai 2007)

Thomas Buergenthal, Ein Glückskind. Hörbuch, Interpret: Uwe Friedrichsen, mit einem Epilog von Thomas Buergenthal. Düsseldorf, Patmos, 2008, ISBN 978-3-491-91270-0.

Lectures

A Brief History of International Human Rights Law in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

“The Lawmaking Role of International Tribunals,” Dean Fred F. Herzog Memorial Lecture, October 17, 2011, The John Marshall Law School, Chicago, Illinois.

Thomas Buergenthal was helped by the love of his parents and their example not to give up even in great danger. Without the help of other people who supported him in the face of extreme danger, he and his family would not have been able to survive the flight from the Nazis, nor would he have been able to survive the camps without them.

Right to life, freedom and security

Right to truth

INTRODUCTION

“A lucky child” is the title of the autobiography of the US-American lawyer Thomas Buergenthal. The term “lucky child” sounds paradoxical in connection with his story. As a child, Thomas Buergenthal survived the cruel world of the ghettos and the Auschwitz extermination camp. When he was a teenager, he got to know the world of the “Wirtschaftswunder” and the repressed history in the Federal Republic of Germany. Then, as a student, he discovered the USA for himself, where he became one of the most respected lawyers. In an interview, the lawyer explains how, despite all the suffering, he draws conclusions about what humanity and human dignity mean. He became an internationally highly respected advocate for human rights.

Interview with Thomas Buergenthal (German and English language)

By downloading the video you accept the YouTube privacy policy.

THE STORY

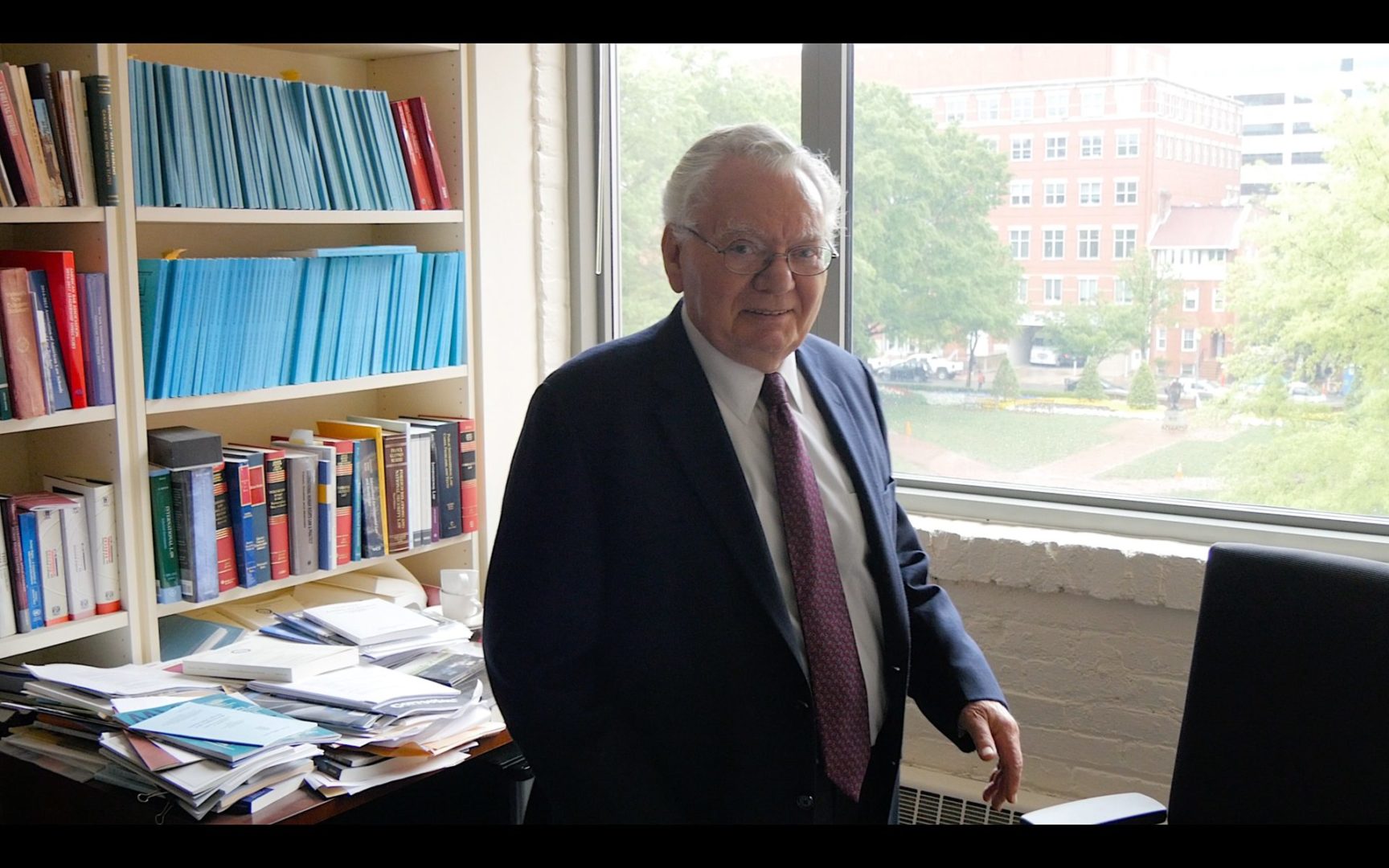

Thomas Buergenthal

“A Lucky Child” – Survivor of Auschwitz, International Judge and Human Rights Advocate

“A lucky child. How I survived Auschwitz as a small boy and found a new life” is the title of the German edition of the autobiography of the US-American lawyer Thomas Buergenthal. The term “lucky child” sounds paradoxical in this context. In Katowice, Poland, Thomas Buergenthal’s mother Gerda had a friend persuade her to visit a fortune teller. She told her that terrible things were coming to her family, which in 1939 did not require a fortune teller, but nothing would happen to her son, whom she called a “lucky child”. Even though Gerda Buergenthal later called this hocus-pocus with a smile, the prediction helped her never to give up the search for her son, from whom she was separated when her transport arrived at the concentration and extermination camp Auschwitz.

Thomas Buergenthal’s story is that of a survivor who as a child experienced the world of ghettos and camps, as a youth the world of the economic miracle and repressed history in the Federal Republic, and as a student discovered the USA, where he became one of the most respected international lawyers and advocates of human rights. He was born in 1934 in Lubochna, a then idyllic place in Czechoslovakia, which is now in Slovakia. Mundek Buergenthal, his father, had fled here to the edge of the Tatra Mountains of the Carpathians in 1933 after the Nazis came to power in Germany. Together with his friend Erich Godal, also an opponent of the Nazis, he opened a small hotel, the “Villa Godal”. On the one hand, in the hope of returning to Berlin soon after the nightmare is over; and on the other, to give political refugees and opponents of the Nazis a safe haven for a while.

In Lubochna in 1933 Mundek Buergenthal met his wife Gerda, a born Silbergleit, who had been sent by her parents from Göttingen on holiday to that hotel. Silbergleit’s parents probably wanted to help the young woman forget a non-Jewish admirer. Above all, however, the 21-year-old Gerda was supposed to escape the harassment of organized Nazi youths in the streets of Göttingen, which was becoming increasingly unpleasant, at least for a while. The meeting of Mundek and Gerda was, at least that’s how Gerda remembered it, love at first sight. After three days they were engaged, eleven months later their son Thomas was born.

From 1939 the family of three was on the run. The fascist Hlinka Guard expropriated the hotel in which Mundek Buergenthal had previously acquired shares and paid off his friend. A short time later they were on their way to the Polish border with their suitcases and nothing else. To be more precise, they were sent back and forth in no man’s land between Czechoslovakia and Poland for a whole week, because the Polish border guards did not want to let the refugees enter. It was an irony of fate that after the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, heavily armed German soldiers, of all people, put the Buergenthal family in charge of crossing the border.

From 1939 the family of three was on the run. The fascist Hlinka Guard expropriated the hotel in which Mundek Buergenthal had previously acquired shares and paid off his friend. A short time later they were on their way to the Polish border with their suitcases and nothing else. To be more precise, they were sent back and forth in no man’s land between Czechoslovakia and Poland for a whole week, because the Polish border guards did not want to let the refugees enter. It was an irony of fate that after the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, heavily armed German soldiers, of all people, put the Buergenthal family in charge of crossing the border.

It was only with the greatest cleverness that Gerda and Mundek Buergenthal managed in the following infinitely difficult years to stay one step ahead of the persecutors. The courage of his parents and their creativity, humanity and wonderful sense of humor, which they found again and again in spite of everything, left their mark on their son Thomas, who was less than five years old when they fled to Katowice. In Katowice, which had become a vanishing point for German Jews in southern Poland, they moved into a small apartment after a short stay in Warsaw and the scene with the fortune teller took place, who predicted to the seven twenty-seven-year-old Gerda that her son was “a lucky child”.

The role model and the ever present, enduring love of his parents and later a Norwegian fellow prisoner, Odd Nansen, helped Thomas Buergenthal, who was left on his own in the end, to survive the Auschwitz death camp and the death march to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where he was finally liberated in April 1945.

Until then, he experienced how his parents – stateless persons that they were – pretended to be Germans, Czechs or Poles as necessary; how they kept looking for and finding an apartment, no matter how cramped it was; also that they made friends with other refugees and almost always managed to get something to eat or drink. He experienced that their visas for entry to England had come from the British Consulate on September 1, 1939, but that it was the very day the Nazis invaded Poland and no more ships left Polish ports for England.

Together with hundreds of other refugees, they were to be deported on a military train across the border to Russia. But the train was attacked from the air and in this situation the father decided that the Buergenthal family should go to Kielce and not to Russia.

For four years they lived in the Jewish ghetto of Kielce in a small room which also served as a kitchen. It was a great advantage that Mundek Buergenthal found a job for a while in the canteen of the German Schutzpolizei, because it allowed him to secretly take meat leftovers home. Life in the ghetto was dangerous and a constant struggle, even between Polish and German Jews. But above all, the ghetto was a legal vacuum, its inhabitants at the mercy of the Schutzpolizei and Gestapo. The Germans organized raids, shot people, humiliated and mocked religious Jews by cutting off their beards.

It was there, in Kielce, that Thomas met his maternal grandparents, who had been deported to the Warsaw Ghetto and who were now – in an almost miraculous way – also taken by his parents to the ghetto of the city. They got a room nearby and with their stories they put the grandson Thomas in a world where “all people lived peacefully together and it was no crime to be a Jew” (1). When the ghetto was liquidated in 1942, the Buergenthals lost track of their grandparents Rosa Blum-Silbergleit and Paul Silbergleit and were never to see them again. Together with 20,000 ghetto inhabitants, they were deported to the Treblinka extermination camp and murdered there.

Mundek Buergenthal, on the other hand, who ran the workshop for the Schutzpolizei in the ghetto, once again managed to save his small family by hiding them in the workshop together with some workers during the liquidations. They were taken to the Kielce labour camp in the autumn of 1942, together with two children, Ucek and Zarenka, who had been taken under the protection of the Buergenthals with a courageous action when their mother was also deported. Thomas Buergenthal’s younger brother and sister, as they had become in the meantime, were murdered with thirty other children when the German extermination furor also swept trough the work camp. He would never forget that day, he writes in his memoirs, when Ucek and Tsarina were taken away. And why did the town commander let him live?

After the labour camp was closed down, the Buergenthals were transported to the Henryków Sawmill, where wagons were made for the Wehrmacht and Thomas worked as the civilian commander’s errand boy, which saved his life again, as he proved to be useful.

After the failed escape attempt of some prisoners captured by the Gestapo, he witnessed executions as a child, which taught him how to spoil the Nazis’ fun. One of the captured prisoners, a young man, put his head in the noose himself and kissed the trembling hand of the prisoner who had to take on the role of executioner, which completely upset the Gestapo officer. Angrily he hurled the chair from under the prisoner with a kick. The dignity and humanity that the young prisoner demonstrated just moments before his murder moved the boy deeply. They encouraged him in the conviction that “moral resistance in the face of evil shows no less courage than physical resistance, an argument that unfortunately often gets lost in the discussion about the lack of a significant Jewish resistance during the Holocaust”. (2)

Auschwitz-Birkenau

In August 1944 Thomas Buergenthal was deported to Auschwitz, separated from his mother immediately after arrival – whom he was not to see again until the end of 1946 – and accommodated with his father in the former so-called gypsy camp. Its inmates, many thousands of Sinti and Roma families, had been murdered by the Nazis shortly before.

How can a child survive Auschwitz, separated from his mother, shaved bald and put into prisoner clothing, tattooed with a number that from now on replaces his name, surrounded by electric barbed wire, screaming block elders and cruel Kapos, prisoners who worked for the camp Gestapo in order to live? How did people manage to preserve human dignity in this environment and under this terror, while others sacrificed their decency and dignity in the hope of surviving?

Again it was a mixture of tactics and luck and compassionate people, especially his father, who came to Thomas’ aid so that he could avoid the selections that took place every few weeks, could hide and above all did not fall ill, which in Auschwitz was tantamount to a death sentence in the gas chamber.

At a time when others lost their moral compass, writes Thomas Buergenthal in his autobiography, his parents showed their strong character (3). And again it was a job that gave his father some protection, this time as an errand boy for a Kapo, a prisoner who worked for the SS.

But there was something else, too, and that was that he rebelled with all his strength against the fate that had been destined for him: “I grew up in the camps, I knew no other life, and my only goal was to stay alive, from one hour to the next, from one day to the next.” (4) He succeeded in overcoming his own mortal fear when, after the separation from his father – which came about during one of the surprising selections in the so-called gypsy camp – he had to admit to himself that there was no way out and that he would die in the gas chamber in a few minutes. With the admission the tension disappeared: “Warmth flowed through my body. I was at peace with myself. All my fears were gone, and I was no longer afraid to die.” (5)

Thomas Buergenthal survived the Auschwitz infirmary, to which he was sent after selection, and a few weeks later was transported to the so-called children’s camp, whose inmates were used to collect garbage. He remained there until the camp was evacuated in January 1945 and even saw his mother again for a few minutes on the other side of an electric fence. He never saw his father again. He died in Buchenwald and not in Flossenbürg, as Thomas Buergenthal only discovered much later, and the boy had to go on the death march to Sachsenhausen concentration camp alone. Only now, he said later, the hardest part of his struggle for survival began, and yet he had the feeling that he had won a victory: “against Hitler, the SS and the whole killing machinery of the Nazis” (6).

Odd Nansen – Rescuer in need, liberation and final section

Thomas Buergenthal reached the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Oranienburg with severe frostbite on his feet. Now there was no choice and he had to go to the dreaded infirmary, two toes were amputated. A short time later he met the Norwegian Odd Nansen, son of the famous polar explorer, who took care of little Tommy, about whom he later published a book with this name as title. Without Odd Nansen, little Tommy would not have had anyone to visit him anymore. When Odd Nansen sat by his bed, his feet hurt less and he could even laugh sometimes, he remembers decades later in his preface to Nansen’s concentration camp notes. (7)

After the liberation of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, Thomas Buergenthal’s last stage of his struggle for survival led him with the Polish army to Berlin and back to Poland. After a long and desperate search, his mother, who had returned to Göttingen, tracked him down in the Jewish orphanage in Otwock. Shortly before he would have left for Palestine, the reunion, which was no longer considered possible, took place. The luck of both was that their surname was not Levy or Cohen, but with Buergenthal an unusual surname. Otherwise Thomas would never have been found on the endless lists of missing persons.

In the years up to 1951, Thomas Buergenthal made up for his missed schooling in Göttingen and soon after followed the promise: “America!” Having set off for a one-year stay, he knew, once he had arrived there, that he would stay forever and start a new life without the constant reminder of the camps.

Odd Nansen, to whom he owed his survival in Sachsenhausen concentration camp, was unforgettable for Thomas Buergenthal. He found him again soon after returning to Göttingen with the support of his mother. They first met in Germany and then he visited the Nansen family in Norway, where he spent a wonderful summer. A lost childhood cannot be made up for, but the laughter, the conversations, the excursions in nature certainly had their healing effect.

The meetings and conversations with Odd Nansen, who wrote a diary about Sachsenhausen, were groundbreaking for the professional future of the young survivor Thomas Buergenthal. In the foreword to the English-language edition of the diary in 2015, he wrote how much the humanist and wonderful person Odd Nansen helped shape his later path: “Whether I knew it or not at the time, my decision to study international law and to work in the human rights field was in large measure inspired by the principles he believed in and lived by.” (8)

Survival means resistance

Thomas Buergenthal has become one of the most important lawyers of our time.

He published his autobiography in 2007 at a time when many responsible people began to wonder what would happen if the survivors of the camps in the struggle against xenophobia and racism would no longer be with us. How quickly can it actually happen that a social mood of crisis brings up the burning question: Did we interpret our history correctly? In this case: Have we really understood the fate of the survivors, their reminders and warnings? Has their resistance in the struggle for human rights become our own action?

Thomas Buergenthal’s fate and life provide an answer to these questions that could hardly be stronger and is highly relevant. His survival is a testimony to a child’s resilience that is not merely touching, but stirring. He confronts us with the fact that surviving Auschwitz does not mean merely being a victim of the Nazis, forever stamped with a concentration camp number and entered on the lists of a terrible extermination machine, which has been reconstructed by the German culture of remembrance as meticulously as the Nazis achieved it before. How history runs and our fate is shaped, as Thomas Buergenthal shows us, depends much more on our own decisions. This is his message that man is the only being that can – and probably must – choose even under extreme conditions. Even in the Auschwitz camp there were people who remained human, and others who left their humanity behind and, as Buergenthal writes, were no longer “human beings”. To say “No!” when injustice is done is what the lawyer Fritz Bauer has formulated with regard to Auschwitz and the Nazi trials; that is and remains our task.

“I wanted to win”, says Thomas Buergenthal, and the feeling of having won a victory against the Nazis and Hitler, which he had when he left Auschwitz-Birkenau in a new state of uncertainty, is deeply engraved in him: “You tried to kill me, but you see, I am still alive!” The extraordinary thing about his story is that he didn’t stop at that knowledge. He does not speak of burdens or guilt that are passed on, much less of dutiful exercises in morality and historical remembrance. The wonderful and almost incomprehensible thing about his story is the realization that a person, a child rise beyond itself and be stronger than death. A truly great plea for humanity and the struggle for human rights, which Thomas Buergenthal has made his life’s work.

A better advocate of human rights

“Perhaps it is obvious that my past attracted me to human rights and international law, whether or not I was aware of it at the time. In any case, it enabled me to be a better human rights lawyer, if only because I was able to understand, not only intellectually but also emotionally, what it means to be a victim of human rights violations. I could feel these things deep inside myself.” (9)

Based on his experiences, Thomas Buergenthal made human dignity and respect for human rights his life’s work.His life in the U.S. began in 1951. On December 4, the seventeen-year-old arrived in New York Harbor. He studies law at New York University and at Harvard University in Cambridge Massachusetts. The boy, who had to spend his childhood fleeing and in camps, earned a Master of Law and Doctor of Juridical Science, became professor and director of the International Rule of Law Center at George Washington University (Washington DC), and devoted all his professional activity to international and human rights law.

Human rights, says Thomas Buergenthal, were still largely unknown at the beginning of his legal career and certainly not a subject of university teaching. But he was not interested in science alone, but in practice, in the application of human rights. For twelve years he held the office of a judge, took over a term as president of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Costa Rica, which he co-founded. In 1992 he was appointed as one of three members by the UN to the Truth Commission for El Salvador, which exposed the terrible human rights violations during twelve years of civil war in the Central American country. From March 2000, he served as a judge at the International Court of Justice in The Hague for ten years, before returning to George Washington University.

Notes

(1) Thomas Buergenthal, Ein Glückskind. Wie ich als kleiner Junge Auschwitz überlebte und en neues Leben fand. Erweiterte Neuausgabe. Frankfurt am Main 2015.

(2) Ibid., p. 79.

(3) Ibid., p. 12.

(4) Ibid., p. 14.

(5) Ibid., p. 98.

(6) Ibid., p. 109.

(7) Odd Nansen, From Day to Day. One Man’s Diary of Survival in Nazi Concentration Camps. Edited by Timothy J. Boyce. Preface by Thomas Buergenthal: “The Odd Nansen I knew”, p. 50.

(8) Ibid., S. 52.

(9) Buergenthal, Ein Glückskind, p. 15 f.

Author and interview: Dr. Irmtrud Wojak

Contact: info@fritz-bauer-bibliothek.de

Camera: Jakob Gatzka