16.09.2020

Diane Foley is committed to protecting the rights and security of journalists in war zones

Diane Foley is the mother of American photo and video journalist James W. Foley, (1973-2014) who in 2012 was kidnapped by Islamic extremists. He was brutally executed two years later, as were three other American hostages. Diane Foley is the founder and president of the James W. Foley Legacy Foundation. Annually, the foundation recognizes the courageous work of human rights defenders and journalists with the James W. Foley Freedom Awards. You can find information about this year’s event (“Moral Courage in Challenging Times”) and the current honorees here

Diane Foley is the mother of American photo and video journalist James W. Foley, (1973-2014) who in 2012 was kidnapped by Islamic extremists. He was brutally executed two years later, as were three other American hostages. Diane Foley is the founder and president of the James W. Foley Legacy Foundation. Annually, the foundation recognizes the courageous work of human rights defenders and journalists with the James W. Foley Freedom Awards. You can find information about this year’s event (“Moral Courage in Challenging Times”) and the current honorees here

“Jim’s work was about the truth – we can cover it up and we can forget it, try to go past it, but there are some truths that are hard to escape. And certainly one of those is the horror that war is for civilians and children, for an entire population.”

Also on our Podcast

Interview by Susanne Berger

Jim was always interested in other people, other cultures

SB: Maybe we can start off with you telling me a little about your son. Who was James Foley?

SB: Maybe we can start off with you telling me a little about your son. Who was James Foley?

DF: Okay, sure. Jim was the oldest of our five children and was born while my husband was doing his medical internship in Chicago. He was born in Evanston Hospital in Illinois, but his primary childhood years growing up were in New Hampshire. We came to Wolfeboro, New Hampshire – that is actually our home state – when he was age six. Jim went to school here and grew up in a very rural, homogenous part of the United States. We were just middleclass folks, living in a beautiful part of the country, very few minorities, limited poverty or adversity, just a really pristine area in our country, shielded from a lot of the problems that were going on in cities and in the south. I really feel Jim’s eyes were opened when he went off to college. He did his undergraduate work at Marquette University of Milwaukee, Wisconsin which is a very racially segregated city with poverty and other social issues. Marquette University sat right on the border of a very economically deprived part of the city. The students, from the beginning, were encouraged to volunteer, to be mentors and help students in the inner city schools. So, Jim’s eyes were really opened, I think, rather abruptly to a different side of the United States. And he spent a lot of time doing volunteer work and then later, in his college career, he went on to do several trips to American Indian reservations. I think this exposure opened his eyes to other cultures and the economic insecurities within our own country. Jim was very interested in all kinds of people and cultures and he was particularly touched by the adversities a lot of people faced within our own country, initially.

SB: Did he always want to be a journalist?

DF: Not at all. But I guess in retrospect, he had a good basis for it because he loved to read as child. He loved to be read to until he could read himself and then once he could, he was always reading. He loved history, loved to learn about other places and people and, again, other cultures. He also loved to write and travel. My mother is from Ecuador and his uncle from Spain and so, even as a youngster, he was very interested in the Hispanic culture. For example, at age 11, he accompanied my sister to Spain, to care for her younger children. When he attended university, he majored in history and Spanish. Jim was also gifted with the ability to really listen. That’s why he always had so many friends, because he loved to hear people’s stories.

SB: If you had to describe your son, if you had to put it in just three words, how would you describe James?

DF: That’s an excellent question and not that hard to answer. Jim was very compassionate, he was courageous and very committed. He was also fun loving, but I think as he matured, the other three were the primary aspects of his personality. Once he made a decision to do something, he was all in.

SB: It seems that when he decided to become a conflict journalist, he somehow felt that it was truly the one thing that combined all of his ideas, that he had found his passion?

DF: I think you’re right, because he initially did a lot of teaching, when he was in graduate school, through ‘Teach For America’. And he again worked in the inner city and saw a lot of the other side of America, some of the injustices and racial segregation which troubled him a lot. But he never felt he was a good enough teacher and I think that’s why he wanted to write and eventually felt drawn to real stories, true stories, if you will, and journalism. It took him a while, though, to find his path, but once he did, he was really committed to it

SB: As I was reading about James, the one word that I came up with in my mind was that he was in a way very authentic and also, I think, unflinching. He was willing to record the suffering of the people that he met and to try to bring the reality of war, these terrible conditions, to the public, unedited. But you can only do that when you do not shy away from that reality. That impressed me very much about him.

DF: Well, yes and I think he had a curious mind. He really was interested in why people did what they did. Even when he began as a conflict reporter, one of his first assignments was being embedded with the US Army, initially with the National Guard out of Indiana. He was curious about why young men choose to be soldiers and then, once he got to Afghanistan and Iraq, he was very interested in the people there and their cultures and how our military presence affected them.

SB: I saw this one video that he made, where he interviewed members of the Libyan opposition forces fighting against [Libyan dictator Muammar] al-Gaddafi, a postal worker and a mid-level bureaucrat. And here they all are, in this militia, in the middle of this conflict. So, I think he really wanted to document the very human side of the story, he wanted to get to our shared humanity.

DF: I think he felt that very strongly, amid the beginning of the Arab spring which really began in 2011. And he was particularly interested in why these people were willing to risk everything, literally, lives, family, homes to obtain the freedom to live in a different way than they were experiencing. Jim was very interested in that and felt it was something the world needed to hear. He was also quite concerned because he realized a lot of journalists were pulling out, particularly journalists attached to the large media companies, because the danger was increasing, and Jim was very aware of that.

He felt that the truth was important

SB: Did you notice any change in James, as a result of his experiences? The harshness of war, the brutal conditions, how did that affect him?

DF: It affected him very deeply. Jim had always had a fun loving, optimistic nature and he became much more serious, much more committed. He developed a real passion for hearing these stories and telling them. He became much more focused and as I say, serious.

SB: Would you say that he was in some way compelled, that he felt like he had to do what he was doing?

DF: Absolutely. Friends and family, we all tried to dissuade him, particularly after his 40 days of detention in Libya. We very much tried to dissuade him, but it was something he really felt compelled to do. He felt that the truth was important. People needed to know how much these people were yearning for freedom, they were willing to sacrifice everything. So absolutely, it was something he felt compelled and committed to do.

SB: When James went missing in Syria, how did you realize that something was seriously wrong? How long had he been in Syria before he was abducted?

DF: Jim first went to Syria in early 2012 and he was very cautious and used all the [safety] technology that was available at that time, although it’s improved tremendously since then. He went in and out of Syria multiple times in 2012 before he was captured at the end of November of that year. As a matter of fact, he was home in October of 2012, for his birthday. We were acutely aware of how much more dangerous the situation was becoming. On his last visit, he promised to be home for Christmas, that he’d be back.

SB: How much did you know about the group that had captured James and held him hostage or the conditions of his imprisonment? From what I understand, you knew very little.

DF: We knew nothing. As a matter of fact, we didn’t even know if he was alive until September of the following year, 2013. He literally disappeared and since he was a freelancer, he had no security team or anything like that. Thankfully, one of his employers was able to hire a security team to search for him, but they couldn’t find him. They really thought he had been detained by [Syrian dictator] Bashar al-Assad’s people and was being held at Damascus, which was not the case. It was only much later that we realized that he had, in fact, been taken by a jihadist group and was held in Northern Syria. So we had no idea and our government didn’t seem to know either. We were told the U.S. had no assets [or sources], if you will, in Northern Syria and the FBI mainly asked us for information. So we really had no idea if he was alive or not those first eight months.

SB: How did you finally learn which group held him, in whose hands he was?

DF: The security team working for [James’ employer] The Global Post at the time thought, Assad’s military had kidnapped him, whereas others had no idea. Jihadist groups were starting to infiltrate the country but people did not really understand who was who, there were many factions, many foreigners coming in, so it was rather chaotic. So we really didn’t know. We eventually had two people who gave us eye witness testimonies that Jim was alive and that was in September 2013. It was actually through a Belgian citizen, Dimitri Bontinck, who skyped with me one day, saying that his son, Jejoen Bontinck, a Belgian teenager, had seen Jim and told us exactly where he was being held in Northern Syria. And then a month later, Omar al-Khani, who had been detained by the same jihadist group, also said that he’d heard Jim’s name in the prison and knew that he was, in fact, alive and being held with many other international captives. And then about a month after that, in November 2013, we received an email from the captors. However, they didn’t identify themselves, except that they very obviously hated the United States and that Jim, being a U.S. citizen, was the target of a lot of their hatred. We didn’t know Jim was with three other until 2014, when some of the captives were released.

I’m so grateful for the people Jim was with… There was a lot of goodness surrounding him

SB: That must have been a very difficult but also a very important moment to meet these other captives. One of the most moving parts of the documentary that you have made about Jim’s life is when they talk about how much Jim helped them in their own struggle to survive. What do you think gave him such strength?

SB: That must have been a very difficult but also a very important moment to meet these other captives. One of the most moving parts of the documentary that you have made about Jim’s life is when they talk about how much Jim helped them in their own struggle to survive. What do you think gave him such strength?

DF: Jim was always a good hearted person, he really was, but he grew and matured as an adult whom I really didn’t know in that way. I think during his captivity he turned to his faith in God and really spent a lot of time in prayer. That’s why I believe he found the ritual of the five calls to prayer in Islam, to pray five times a day, very helpful because I think it helped him to focus and to pray for strength. And I was really relieved to hear what the surviving hostages say about Jim’s prayer and goodness, because I think that prayer did strengthen him and enabled him to stay human and not allow the captures to rob him of his soul, no matter what they did to him. I am so grateful for that. I and many who loved him also were praying on this side of the ocean for him. And I really feel altogether, it was the power of prayer and God’s goodness and mercy that gave him the strength.

SB: In many ways, as these fellow prisoners say, James gave them the strength to survive.

DF: Well, he tried. Jim was always a people person. I was very grateful that Jim was with other people, very good people. There was a lot of goodness surrounding him. And, knowing Jim, he would’ve been very interested in the international array of prisoners he was held with. There were four Frenchmen and there were Spanish and Danish and German citizens, Italian journalists and humanitarian workers, all incredibly interesting and good people. I’m so grateful for the people he was with. I’m sure he enjoyed their company, even in spite of the horror of what they went through. They became very close.

SB: I asked you this in my letter yesterday: Do you somehow see your son differently now? Is there something that you learned about him that you didn’t realize before?

DF: Definitely. He was the oldest of our five children. He was always a very loving son, very thoughtful, kept in touch, even when he was far away, because he knew we worried. That’s the side I saw of him. But I never knew of his deep goodness to others and it was partly through those who witnessed the last few days of Jim’s life, but also through the hundreds of people who have told us the impact Jim had on their life – from students in ‘Teach For America’, who formed their own non-profit to continue Jim’s legacy, to people he just happened to meet, people from the Middle East, and on and on. So, I didn’t know these things about Jim. Jim would just tell us he was a lousy teacher and that’s why he was going to do writing and we never knew that he continued to mentor many of his students once he became a journalist. We just had no idea how many lives he had touched or that he aspired to be a man of moral courage. As a parent, it’s hard to know the adults our children become particularly if they are humble like Jim was. He really wanted to know how we were when he came home, he didn’t talk much about himself.

Moral courage and inescapable truths

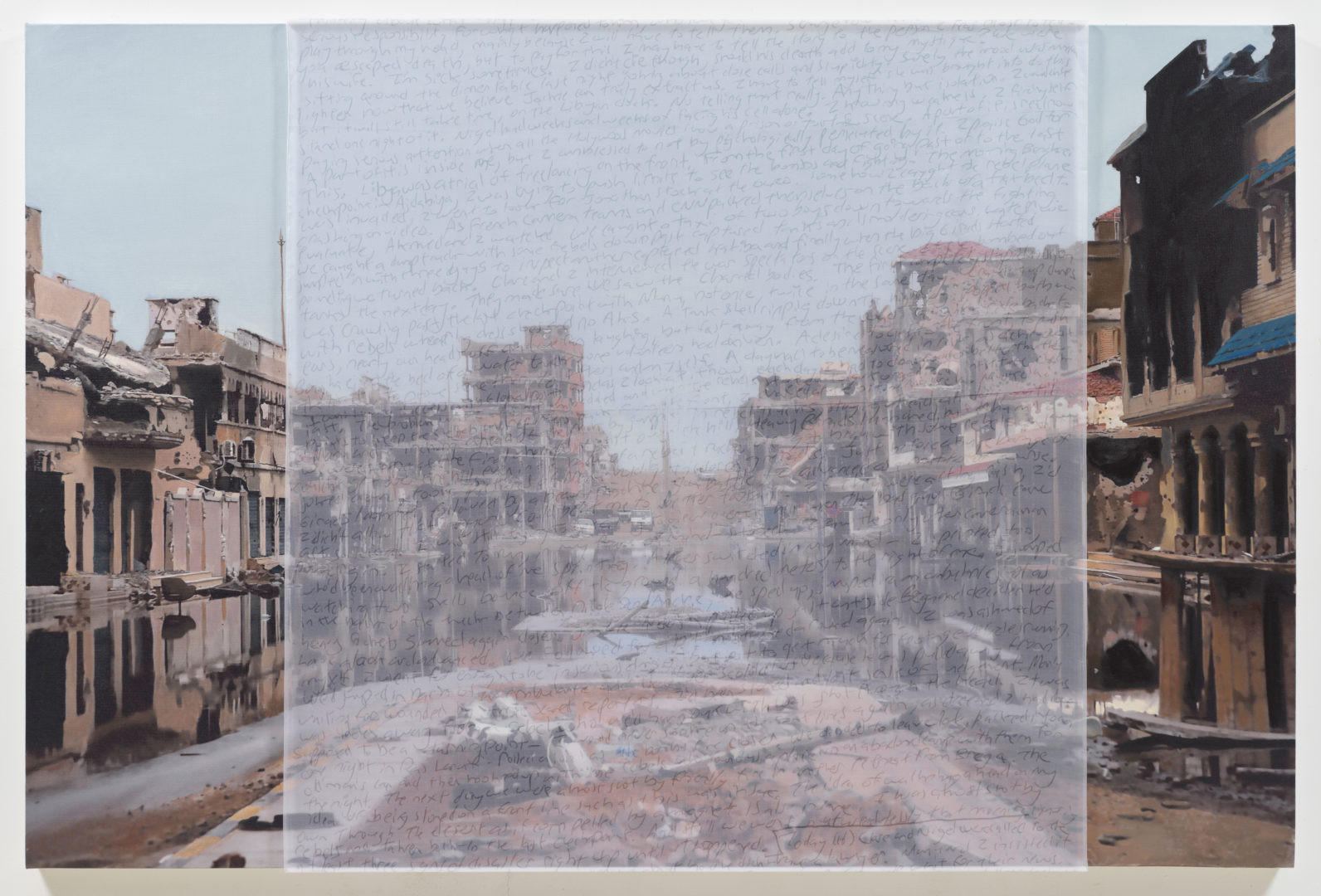

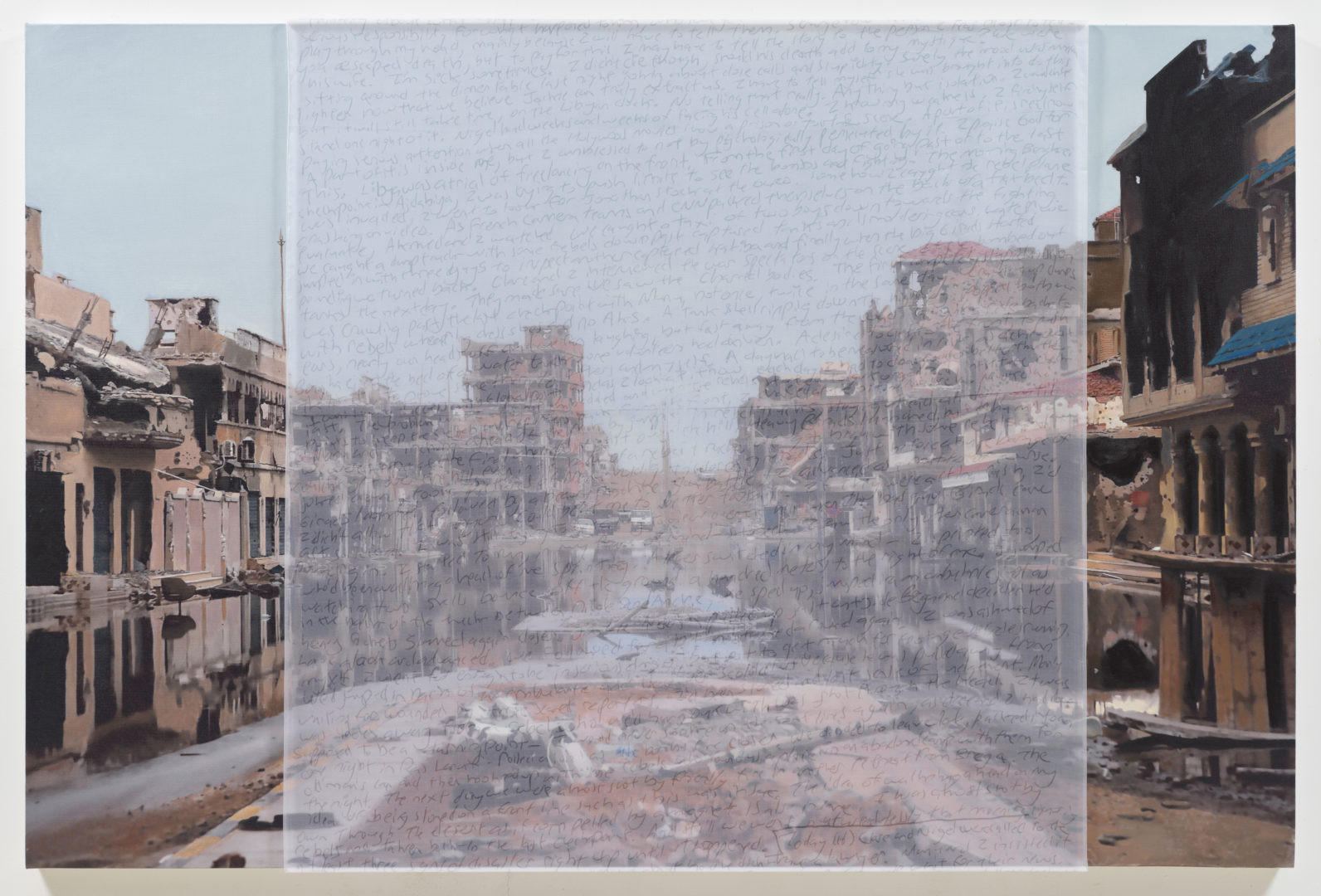

SB: You commissioned a series of art works to preserve Jim’s memory and also to keep his work alive. The title you chose for this series of paintings is “Inescapable Truths.” How did you and the artist Bradley McCallum arrive at this term?

DF: Well, first of all, we did not commission these works at all. Bradley, out of the blue, reached out to us. He is a human rights artist who has done a lot of work on Apartheid in South Africa. He had heard about Jim. and he was very interested in Jim’s legacy and how to find some way to artistically convey what Jim was trying to do in his work. So he approached us and, serendipitously, we happened to have an old backpack of Jim’s with some B-roll of photographs he’d taken and video, primarily from Libya, which this artist embraced and used, really, for a lot of the basis of his paintings. The title was difficult to come to, we went around and around, looking for the right title, but I’m pleased with it because it is about the truth – we can cover it up and we can forget it, try to go past it, but there are some truths that are hard to escape. And certainly one of those is the horror that war is for civilians and children, for an entire population. So, I think a lot of that is very poignantly captured in some of those paintings.

SB: Yes, I think James was really willing to take that on, which is not an easy thing to do. Also in terms of his fellow captives imprisonment. I think that’s why people responded so much to him. They felt his authenticity and honesty, how they were met by him. But it’s very difficult to stay this strong when you are confronted with your own mortality, with these raw fears. It shows what a substantive person he was.

DF: Well, Jim really thought about life. I think that partly came from reading. He really read very broadly, was very interested in spirituality and the role of religion and faith and the strength that it gives people to endure horrors, adversity and deprivation. Jim had explored a lot of that personally and that is, I think, why he was interested in the Islamic faith and in why people would risk so much. He was very intrigued about all of that. Jim aspired to be a man of courage, of moral courage, particularly. He always had a physical courage. But moral courage, he recognized, was the greater courage and he felt compelled to do his little bit through journalism. That would be a way to express the truth about the horror of what was actually happening in Syria, for example. It was something he aspired to in a big way.

SB: I think he truly met the moment. I remember that he says in the documentary [about his life]: “What good is it if I just have the physical courage to report the story, but then not the moral courage to make sure that it is actually reported?” It shows how much he felt that there has to be a commitment to fight for the truth and to insist upon it. That is not easy to do.

DF: It isn’t and that’s partly why we, The James W. Foley Legacy Foundation, work to protect journalists who try to investigate, report with integrity and really seek the truth. It’s not an easy time to be a journalist because there’s a tremendous push back. A lot of people don’t want to see the truth, don’t want to hear the truth, with allegations of “fake news” and other things in the mix. It’s become very difficult to even ascertain what is, in fact, true.

“No concessions, no negotiations” – a fatally flawed U.S. hostage policy

SB: I want to talk a little about the work of your foundation. What was its aim, initially, what is it now and has it changed over time?

DF: It has somewhat. It was very hard to decide what to zero in on because Jim had so many broad interests. But because of our ordeal and his own, we decided to focus, initially, on three areas. We have since cut it down to two. We advocate for freedom for all innocent Americans who are kidnapped abroad. And then secondly, we seek to protect journalists worldwide. We also are very interested in various human rights aspects, especially people who are disadvantaged because of poverty or war or conflict. However, we felt we had to drop that piece because there are so few organizations that work for hostage families and the return of hostages and not many who are helping to teach safety practices for young journalists. Therefore, we zeroed in on those two gaps that we had experienced. So, that it is why we focus on helping American hostages. Americans only because there are so many hostages worldwide, we knew we couldn’t take that on. We felt we had to narrow it to U.S. nationals who are unjustly detained or taken hostage abroad. To protect journalists, we have a preventative journalist safety curriculum at the undergraduate and graduate level that we seek to promote, along with our collaboration with all non-profits who work for press freedom. We’re very interested in the preventative side, so that students aspiring to become journalists and freelance journalists know how to protect themselves and the people they report on. Not easy these days.

SB: You have been very open to say that you felt completely overwhelmed when you were first confronted with this crisis of your son being taken hostage in 2012. Looking back, what was the most serious problem that you faced at that particular time? What was the hardest part of this ordeal, in terms of trying to get information and trying to assist your son?

DF: Well, I think one of the hardest things was the unknown. We did not know if Jim was alive or not. And also, we were told by FBI to tell nobody, so even though we found out at the end of November 2012 that James was missing, we went through Christmas telling no one but closest friends that Jim was in fact kidnapped again. So, I think it was very hard not to cry out for help because the FBI told us to be quiet, that they had it covered, that Jim was their highest priority. But it was very difficult when the first FBI agent who came to our home didn’t speak Arabic, didn’t know anything about Syria, had never been to the Middle East, didn’t ask anything about Jim’s cell phone or anything. It was just very disturbing. As a matter of fact, he told us we should reach out to President Assad for help to find Jim. So, it was very upsetting to find out that this person, who had no clue about what was going on, was in charge of Jim’s investigation. That was very hard and then to hear nothing – that was incredibly difficult. So by the beginning of 2013 we decided as a family to go public, I particularly was frantic to get help from somebody. So, we reached out to the media initially to see if anybody in the international media anywhere had any information. We made some noise to find out if somebody, anybody had seen or heard from Jim and then I began my trips to Washington, just trying to get some attention for Jim’s case. But the hardest part was that there was nobody in Washington whose job it was to, whose priority it was to bring American hostages home. There was simply nobody. There were many people who were kind and patronizing, who would take a meeting with me and tell me that Jim was their highest priority. But that was not really the truth because nobody had any information for me, and it was nobody’s priority, nobody’s job to find Jim and bring him home.

The successful fight for reforms

SB: So you were left completely to your own devices.

SB: So you were left completely to your own devices.

DF: You’re right. At the time I didn’t realize it was four Americans who were being held hostage, not just Jim. There has been a lot of improvement in the wake of Jim’s death, followed by Israeli-American Steven Sotloff’s death, a Florida journalist, and then Peter Kassig’s and human rights worker Kayla Mueller’s death. I think it’s important that people realize that. Also, earlier that year American journalists Marie Colvin, Luke Somers and businessman Warren Weinstein had been killed. So, in the wake of all those murders, there was an outcry and, to his credit, President Obama did ask the National Counterintelligence Center to conduct a complete review of how our government handles hostage cases, which included interviewing hostage families. The outcome of that was that in June of 2015, Obama announced a new policy, Presidential Directive 30, which created the Interagency Hostage Fusion Cell, now housed at the FBI. It includes representatives of all the intelligence agencies, the State Department, all branches of the military, as well the FBI itself, all under one roof. Its priority is to bring American hostages home. They also appointed a Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs at the State Department, at the ambassadorial level, to handle any hostage related issues that require diplomatic action, meaning the State Department’s expertise. And the final piece of this Directive was to have representation at the National Security Council level, so that the White House was acutely aware of all hostage takings and could act on any of the plans or strategic recommendations from the Hostage Fusion Cell and the Special Presidential Envoy.

After Jim’s death, I worked hard with the national counterterrorism group to share our horrific experience. The Foley Foundation continues to work closely with the U.S. Hostage Fusion Cell, the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs and the Hostage Recovery Group. To evaluate the results of this new hostage structure, JWFLF began an annual qualitative research report on the experience of American hostages and their families in 2019, called “Bringing Americans Home”.

To President Trump’s credit, the return of innocent Americans taken hostage or unjustly detained has been more of a priority for this administration. So, there has been some progress.

SB: You have asked people to challenge their personal assumption regarding the official U.S. hostage policy of ‘no concession, no negotiations’ Can you explain a little more what that policy was about? Is that policy still in force today or does it exist in a different form?

DF: That’s a great question because it has become the official policy, but in many ways it’s more of a slogan, if you will. ‘No concessions, no negotiation’, that was the pervading thought back in 2012 and I didn’t realize it at the time, but President Obama felt very strongly that it was essential to maintain this very strong posture of no negotiations with terrorists. And because Jim was taken by a terrorist group, the FBI would not in any way interact with them which of course left the families, meaning us, to interact with these captors, which was ridiculous, really. Our country could have gleaned so much intelligence through our expert officials trying to negotiate with the captors, as opposed to us families who had no idea what we were doing. But the other thing, even more concerning, is that once we did actual research, as the studies conducted by the Rand Corporation, the [U.S. Military Academy] West Point and others show, it became clear that American citizens, as well as British citizens, whose governments adhere to this ‘no concession’ policy, in fact end up doing much more poorly than countries who are willing to find ways to negotiate for the lives of their citizens. There’s actually a small book that was written by Joel Simon, the executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists in New York, called We Want to Negotiate: The secret world of kidnapping, hostages and ransom (Random House, 2019). It really helped us to see that there are ways to negotiate without necessarily making concessions, that make terrorists wealthy or more powerful. That there are shrewd ways of negotiating with captors that may, in fact, make a lot more sense. It’s become a real problem. A lot of governments now see that abducting people is a great way to apply pressure to our country and others. So, it’s been a tactic for centuries, but it continues in a big way and that is why we continue to advocate for the return of our citizens and for information for families, support for families, because it’s a horrific experience for any family.

SB: You yourself have actually commissioned a formal study which shows that, the ‘no concession’ policy is failing to do the one thing that it actually aims to do, which is to make American lives safer. In many ways, it has had the opposite effect.

DF: Exactly. Our citizens don’t come home as often as those of other countries. And other countries are rather shrewd about how they go about it. It really speaks to the question of how important are our citizens? How protective is the US passport? Is that something that is really going to protect you in that situation or not? And we’re finding that if Jim had been French or Italian, he’d be home, whereas the British and all the Americans who were captured by the same group all were killed.

SB: Is this policy still in force or has it been adjusted? What is the current status of it?

DF: Well, it still has a lot to do with the leadership of the administration. We still say that we do not negotiate, or rather that we do not make concessions to terrorists. We are allowed to negotiate and that is what I want our government to do. I feel it’s essential that our government be willing to negotiate with anyone who is holding one of our citizens. It’s a human rights issue, that our government needs to care about that person. However, concerning the making concessions – that’s where our government is more flexible, if you will, not as stringent as President Obama was, that they wouldn’t even talk to them. Now our government is willing to negotiate, and at least consider ways to bring people home, to free them.

Accountability is essential

SB: In terms of bringing those who committed these horrendous crimes to justice, what are you trying to do to fight impunity against these crimes? And can there ever be such a thing as justice? What does that word mean to you?

DF: I think if we have total impunity, no accountability, there’s no justice at all. I do feel it’s essential that we seek accountability. We must have the patience and tenacity and commitment to that. I do not see the drone killing of various leaders, the extreme jihadist leaders, as very helpful because I think it tends to breed more hatred. I think it’s extremely important that people who have done these crimes against our citizens be brought to trial in a fair and transparent way. In the case of the two former British jihadists – Alexanda Kotey and El Shafee Elsheikh – who according to the testimonies of surviving hostages have been identified as members of the kidnapping cell and who were captured in 2018 and are currently being held in Iraq, it’s very hard to get any movement on their case. In August 2020, our Attorney General decided to waive the death penalty, so the U.S. could have access to U.K. evidence. This means extradition of Kotey and ElSheik to the U.S.for trial may be possible in the fall of 2020.

I don’t know if it’s possible to achieve true justice in this life, to be honest, but I think we should have accountability and my hope is that eventually they will be brought to trial so that people can know the atrocities they did. And that, if convicted and guilty, they should spend the rest of their lives in jail, imprisoned. But when I think of the hundreds of thousands of people who have been killed in Syria, there are such atrocities that also need attention. There are the Yazidi massacres and it just goes on and on. But I do think the fight for accountability is essential and we need to protect the human rights of those who are captured (the kidnappers), too, I think that’s important. But, again, the truth, needs to come out. But I don’t think killing one another through drone strikes or other attacks is way to peace because I think, again, it just causes more hatred. It’s complicated, isn’t it?

SB: It’s terribly complicated because also by using drone strikes you, in a way, elevate these people to martyrdom which is a way to attract young people to the cause. This brings me to my last question. You said several times that you underestimated – and basically we all did – the degree of hatred that these groups, and radical Islam in general, have towards westerners. What do you think is the answer to break this cycle of violence and hate? What can we do, what is the solution?

DF: Well, I don’t think isolation is the solution. I think the opposite. I think we need to be interested and care about, understand other cultures, for sure. I think a lot economic insecurity and poverty is often at the root of it, and racism. One example is these British jihadists who had the privilege of growing up in the UK. Several were able to go to college but just didn’t feel like they fit in and they felt stigmatized by their ethnicity, and marginalized. So, I think a lot of it has to do with improved economic security and just coming to understand one another and that’s why I think it’s very important that young people come to value and appreciate different cultures and different races, different religions because that’s part of our world. And I think until we have a real respect for one another there’s always going to be war. I don’t think secularism helps much either. I think we need to believe in something greater and more loving and merciful than ourselves. I think we human beings, can get very self-centered. I think it begins one person at a time, by understanding one another, forgiving one another and seeking peaceful resolutions for conflict. Trying to reduce poverty [is important] because that obviously can be a huge issue. So, it’s a lot of the things that I think our country, too is being faced with right now. Certainly, on a bigger scale, it happens all over the world. Not easy to do, not easy at all. It requires a particular type of leadership and moral courage, too.

SB: Which brings us right back to your son. It was exactly what he was doing, trying to reach out to others, trying to create a better world through understanding. Thank you very much for taking the time to speak to me today.

Interview: Susanne Berger, BA (Washington D.C., USA)

Translation: Dr. Irmtrud Wojak (Bochum, D)

Fotos: Fotos: Diane Foley, the mother of the murdered photojournalist James W. Foley, and the artist Bradley McCallum with paintings Mr. McCallum made based on Mr. Foley’s photographs and his chronicle of war’s human cost. Credit: Andrew White for The New York Times; Stacey Stowe. “Life After Horrific Death for the Journalist James Foley”. The New York Times, December 21, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/21/arts/design/james-foley-bradley-mccallum.html

Contact: info@fritz-bauer-blog.de