15.01.2020

Smart Sanctions: Fighting Impunity through the Global Magnitsky Act

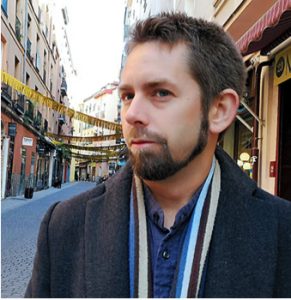

The Director of Safeguard Defenders, Peter Dahlin, explains how civil society can bring serious human rights violators to justice

Background

At the center of the current sanctions debate is the question how governments, as well as other social and political entities, most effectively punish gross human rights violations and other serious breaches of international norms and rules. One of the greatest challenges remains to stop human rights violations as they are occurring, or to prevent them altogether. Relatively new sanctions regimes, like so-called targeted or ‘smart’ sanctions, are considered to be more effective because they target specific human rights violators quickly and directly. In doing so, they allegedly provide an important deterrent effect, which means they supposedly prevent new human rights violations from occurring.

The most well-known example of a targeted sanctions regime for human rights is the Magnitsky Act, named after Russian tax lawyer Sergei Magnitsky who was jailed and brutally tortured in Russian prisons in 2009, after testifying in a massive tax fraud scheme allegedly committed by Russian authorities and the Russian mob against his employer, the British investment company Hermitage Capital Management.

The legislation was first proposed by the British businessman William Browder, owner of Hermitage Capital, who has led a tireless campaign to punish those responsible for Magnitsky’s death. Browder central argument is that the global expansion of the law will provide governments and human rights advocates with important new tools in their fight to hold human right violators accountable.

The Magnitsky Act imposes two types of sanctions: Travel and visa bans as well as asset freezes. The original Magnitsky Act was passed in the US in 2012, punishing Russian officials implicated in Magnitsky’s murder, including (Russian) individuals profiting from this crime. Since 2016, the law applies globally, allowing the US government to impose sanctions against human rights violators regardless where these crimes occur. Other countries that have adopted similar legislation – a full or partial Magnitsky Act – are Canada, the U.K., Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

On December 9, 2019, one day before the 71th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the European Ministers of Foreign Affairs unanimously agreed to adopt a proposal by the Dutch government for an EU-wide Magnitsky Act (EU Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime). The legislation is expected to be formally enacted later this year. Australia, too, is currently considering the introduction of a Magnitsky Act.

Q&A with Peter Dahlin

Q: Safeguard Defenders’ has just released its most recent publication Fighting Impunity: A guide on how civil society can use Magnitsky Acts to sanction human rights violators (Safeguard Defenders, 2020). It is essentially a step-by-step guide how to file a formal complaint against human rights violators in countries that have adopted so-called Magnitsky legislation. Why now, what makes this publication so urgent?

Q: Safeguard Defenders’ has just released its most recent publication Fighting Impunity: A guide on how civil society can use Magnitsky Acts to sanction human rights violators (Safeguard Defenders, 2020). It is essentially a step-by-step guide how to file a formal complaint against human rights violators in countries that have adopted so-called Magnitsky legislation. Why now, what makes this publication so urgent?

PD: The main problem we are trying to solve is that the Magnitsky Act looks fine on paper. However, unless it is enforced, it has no value. We have been told by several government that in order to apply the Magnitsky Act, they need information, they need targets. And so far, NGOs and civil society have not been very active in filing complaints against such potential targets, meaning human rights violators. So, what we want to do is to get civil society more involved in this process, to file complaints. That way we can take it from a theoretical tool to a practical one, in terms of defending human rights. So, we are trying to solve that one specific problem – how does civil society become more involved in getting this act off the ground? Because there is so much potential here. Many countries already have different kind of tools that they can use to sanction perpetrators of gross human rights violations. But with the Magnitsky Act, you have an entire new framework for doing that. There are so many different things that can be done through this act. The fact that you can go after specific individuals rather than groups, organizations or countries – that has a lot of potential, I think.

Q: You say there are so many different things you can do with this Act. Can you give some examples? What makes it different from other sanctions, from other punitive measures?

PD: Well, it ranges from asset freezes, for example of bank accounts, property, etc., as well as travel bans. Also, if your assets are frozen, it tends to have an effect outside your jurisdiction. If the U.S. government, for example, issues a freezing of your bank accounts, it’s going to have a ripple effect in many other territories. So what you really want to do and what the Act wants to do is to go after the spoils of these violations. Because many people who partake in these gross human rights violations do so for monetary interest, for money. And that is really what you are going after. That and their ability to travel freely in the Western world. That is of course especially big when it comes to Russia, but also, for example China.

Q: When you say that this affects peoples’ ability to partake in the international financial system, their ability to travel, it clearly impose a certain hardship on those perpetrators with international contacts. But what about human rights violators who are poor, with no connections outside their own countries. Do you still see a punitive effect of the Magnitsky Act for them?

PD: Yes and no. Many perpetrators on the lower level they do not usually have access to international travel, they do not use international banking facilities, etc., there is a lot less that can be done. But a lot of these people, especially in China, they do use Hong Kong, which I think is about to overtake London as the greatest financial hub in the world. So, a lot of so-called lower level perpetrators actually can also feel the consequences of this. But even for those perpetrators on the most local levels, like a prison guard at a detention center, the symbolic knowledge that they are being singled out, that they are being sanctioned, even if it has no direct, practical effect, is of course an important tool anyway. Especially also for the future, because most of these people think in terms of the future. So, even if you cannot freeze their bank accounts, because they do not have any relevant assets, it does not mean that it is not a useful tool to go after them.

Q: So, you are basically saying the sanctions imposed by the Magnitsky Act have also a very serious psychological effect.

PD: Yes, I think so. For perpetrators, the knowledge that you are being watched, the knowledge that in the future you might be in a position to travel or to purchase property or have assets abroad, that’s going to be a problem. Of course that is going to weigh on them. It is not as effective as if they can be targeted directly, but there is a symbolic value and I think there is a psychological value as well.

Q: You say in your new publication that the primary purpose of the Magnitsky Act is not to punish human rights violators but to change their behavior. Can you explain this a little bit more?

PD: It is quite similar to what we are doing with CGTN (Chinese Party/State Television Broadcaster) where we keep filing these complaints against them when they broadcast material that is clearly against the law, such as forced confessions of individuals in detention. The point is not really to have CGTN’s license revoked, the point is to respond to these violations in such a way that they realize they cannot continue doing it. The Magnitsky Act is similar in that sense that if we are successful in going after individuals that can be proven to have conducted gross human rights violations, it’s going to raise the bar – it’s going to raise the cost for the Chinese government to continue doing it. If people can see that this act is actually being implemented, it will be a lot harder to continue the practice. So, the actual targets of the Magnitsky Act themselves are secondary. I believe that if you apply it systematically you are going to see a difference. It’s going to be more difficult, for example, for police to behave in an abusive way because they know there are going to be consequences. It raises the costs of committing these kind of gross human rights violations.

PD: It is quite similar to what we are doing with CGTN (Chinese Party/State Television Broadcaster) where we keep filing these complaints against them when they broadcast material that is clearly against the law, such as forced confessions of individuals in detention. The point is not really to have CGTN’s license revoked, the point is to respond to these violations in such a way that they realize they cannot continue doing it. The Magnitsky Act is similar in that sense that if we are successful in going after individuals that can be proven to have conducted gross human rights violations, it’s going to raise the bar – it’s going to raise the cost for the Chinese government to continue doing it. If people can see that this act is actually being implemented, it will be a lot harder to continue the practice. So, the actual targets of the Magnitsky Act themselves are secondary. I believe that if you apply it systematically you are going to see a difference. It’s going to be more difficult, for example, for police to behave in an abusive way because they know there are going to be consequences. It raises the costs of committing these kind of gross human rights violations.

Q: As the title of your publication suggests, you see a very important protective function of the Magnitsky Act?

PD: I think so, yes. Not just the knowledge that this law, this Act, exists but that it is actually being implemented. That adds a layer of protection for human right defenders who are at risk of these gross human rights violations, especially torture.

Q: So, you are really trying to raise the scale of the Magnitsky sanctions, because the more these human rights violators and violations are singled out, targeted and sanctioned, the greater the cost will be to continue with these abuses.

PD: Yes, and a lot of our work really focuses on raising the costs of doing these things, of human rights violations, and this is one part of it.

Q: The Magnitsky Act is obviously not a judicial/juridical tool, it’s a political instrument. You talk a lot in your publication about very specific national interests that may or may not lead certain countries to impose sanctions. Does this political dimension of the Magnitsky Act trouble you? Does it take away from the objective criteria that would be present and required in a court of law, for example?

PD: I think yes and no. I think it is a problem that it is very clearly a political tool, that the sanctions one can expect are basically based on the political climate. We expect, for example, the Xinjiang situation – the suppression and imprisonment of the Uighur population in concentration camps enacted by the Chinese government – to lead to Magnitsky sanctions. These horrendous crimes certainly deserve far reaching sanctions, also due to the scope of violation. This is essentially a campaign to exterminate an entire culture, through brutal means. However, as we have seen, such sanctions are only now becoming a possibility, as the climate between the U.S. and China deteriorates. We are also hearing talk of a tougher stance on those involved in repression in Hong Kong, again largely due to the continuing protests, but because of the rising tensions between the U.S. and China. Similarly, the recent expansion of sanctions against Iran and Cambodia is certainly tied to important geopolitical factors.

Q: But do these political considerations at the heart of the Magnitsky Act not raise at least some questions about the legislation, in particular the seeming arbitrariness with which it is currently applied?

PD: Yes, the problem at this point is legitimacy. The Magnitsky Act is indeed a political, not a judicial tool, but it can gain legitimacy by expanding the way how sanction targets are selected. As long as annual sanctions lists are very limited and small, and as long as those sanctioned are from countries in conflict with the sanctioning country, it will be continued to be viewed mainly as a political tool. The role of civil society will be key to the expansion of the annual sanctions lists, and also to push for inclusion of those deserving to be sanctioned from other countries that the sanctioning country is not in conflict with. Expansion and systematization of Magnitsky sanctions will limit the perception of it as merely a political tool, and build legitimacy, and therefore the effectiveness of it. We have seen some small steps towards this in the latest US round of sanctions, which included a number of Cambodian targets. But more and quicker expansion is needed. The bigger it gets, the less political it will be viewed.

Q: You refer to “the sanctioning countries”. Do you think it is necessary for individual countries to adopt their own Magnitsky legislation or do you feel it is enough if multinational organizations like the European Union adopt a global sanctions regime (Magnitsky Act). What is the advantage of individual countries adopting this provision?

PD: In the EU, the EU’s foreign policy goals are not entirely the same as the foreign policy goals of individual member states like Germany, Sweden or Italy. I believe it is therefore quite important for countries to enact their own, national Magnitsky type legislation. And we are seeing a push towards that in many countries right now. The European Union, on the EU level, already has certain tools that can be used to issue very specific, targeted sanctions. The problem is that it they are not very well known and not very well used. So, by having a EU-level Magnitsky Act, it is going to greatly increase the ability, in practical terms, of actually getting sanctions issued. But it is not a replacement for individual countries adopting their own Magnitsky Act, not at all. Basically, both are needed, on a national and on the EU level.

Q: A lot of countries, like Sweden, for example, argue that they are subject to EU policy, that they are only allowed to impose certain types of sanctions on the national level. Does this not cause some serious conflicts?

PD: I do not think so. I think it is important to use as much as possible sanctions on the EU level because it is a lot more powerful. The problem is that I think a lot of politicians are using this argument as an excuse not to act. We have seen a lot of this in Sweden, for example.

Q: What are the greatest misconception about the Magnitsky Act, in your view? What do you want people to know or understand about this law?

PD: I think the one thing that makes the Magnitsky Act so powerful and so unique is the fact that it really is the first time we have an actual tool, legislated, going after individual perpetrators. This is not about countries, it is not about groups or organizations. This is about individuals who commit clear, systematic gross human rights violations and the fact that for the first time ever we can really systematically go after these individuals is incredibly powerful, symbolically as well as practically. It is really inspiring, especially for someone like me who works with human rights on a daily basis.

Q: So you feel that the efficacy of the Magnitsky Act is actually very strong or very high? Because this remains one of the main points of discussions, how efficient is this law, actually?

PD: The response we have seen, especially from Russia and from Russia’s leader [President Vladimir Putin], indicates quite clearly that this an effective tool. We would not have seen that kind of incredibly angry response if it wasn’t for the fact that these people who lead and protect these human rights violators, actually see the power of this law. The fact that you can go after the spoils of these human rights violations is going to be very powerful. And we wouldn’t see Mr. Putin being as upset as he is, if he didn’t know that this tool has incredible power.

Q: But what happens, for example, if there is a victim of rape in Mali, for example, and the woman would like to file a complaint – how easy is it for individuals to request sanctions against their assailants, especially when these victims are not powerful, when they are not well connected?

PD: I think the one thing that makes the Magnitsky Act so powerful and so unique is the fact that it really is the first time we have an actual tool, legislated, going after individual perpetrators. This is not about countries, it is not about groups or organizations. This is about individuals who commit clear, systematic gross human rights violations and the fact that for the first time ever we can really systematically go after these individuals is incredibly powerful, symbolically as well as practically. It is really inspiring, especially for someone like me who works with human rights on a daily basis.

Q: So you feel that the efficacy of the Magnitsky Act is actually very strong or very high? Because this remains one of the main points of discussions, how efficient is this law, actually?

PD: The response we have seen, especially from Russia and from Russia’s leader [President Vladimir Putin], indicates quite clearly that this an effective tool. We would not have seen that kind of incredibly angry response if it wasn’t for the fact that these people who lead and protect these human rights violators, actually see the power of this law. The fact that you can go after the spoils of these human rights violations is going to be very powerful. And we wouldn’t see Mr. Putin being as upset as he is, if he didn’t know that this tool has incredible power.

Q: But what happens, for example, if there is a victim of rape in Mali, for example, and the woman would like to file a complaint – how easy is it for individuals to request sanctions against their assailants, especially when these victims are not powerful, when they are not well connected?

PD: At the moment, it is very difficult. Both in the U.S. and Canada the Global Magnitsky Act is still very new. And even though both governments have implemented certain bureaucratic and administrative procedures how to deal with it, it’s all very, very new. A lot of people, even in the respective governments, are not entirely sure how this process is supposed to work. And of course in the UK there is no process at all because they basically said we will not establish this procedure until after Brexit [Great Britain’s exit from the European Union]. So it is very new, which means it is very difficult. It is hard for people to know how to go about and file these complaints and how to do it effectively. But it is also difficult for those working in the government, because they have very little experience in how to manage these complaints. But I think the more you engage with it, meaning civil society, the easier and better it is going to get, because we are really shaping this process right now, as we speak, how it is going to work in the future. The more engagement you have, the better it will be. But yes, it is going to be difficult for individual victims and that is one of the reasons we now have this very complete, comprehensive guide to show not only the procedure behind it [the Magnitsky Act], but the practical realities. As you said, this is partly a political process and the more people realize how they can use it, the better.

Q: How optimistic are you that the Global Magnitsky Act, a global sanctions regime will stick, that it will have a certain permanence? Because one has to wonder if the political climate changes in the United States, for example, whether there is a willingness to keep the legislation or if there will be efforts to overturn it?

PD: That is not really something I can answer, I am wondering about this myself. I am not very concerned about this at the moment. I think it would be very difficult to reverse this trend we are currently seeing in terms of legislating and adopting Magnitsky Acts in different countries but also using this tool. I think the overall political situation is quite favorable. So, I am not concerned about any kind of reversal. I am concerned if civil society is left out and does not engage with the Act. Because, as I said, the more you engage with it, the less political it becomes and I think that is important.

Q: Have you also had some reactions from governments and their respective bureaucracies how to make the Magnitsky Act more user friendly? Because it is quite a complex and cumbersome procedure, and it has to be, when you are presenting evidence for serious human rights violations. There clearly has to be due diligence, but are there any plans or hopes to make the Magnitsky Act more accessible and easier to use?

PD: There are – both in the US and in the UK and to some extent in Canada, there are discussions between governments and groups of NGOs, trying to find ways to increase civil society interaction. The problem with those discussions is that they occurred with the promise of complete confidentiality, so I cannot say too much about this process right now other than that these governments are aware that they need civil society to become more engaged and that they need to make the Act itself more user friendly.

Q: Have you now actually filed specific complaints regarding China?

PD: We have provided the information needed to make Magnitsky filings to the U.S. government, on their request. We have not done such filings technically ourselves, we have just basically given them the information, so it can be an internal process. With this release of this new guide, we are going to make our first official filing against the then-head of CCTV, China’s State Broadcaster, and specifically against one journalist who has been involved in many forced, televised confessions. So that is going to be our first filing in the U.S., in Canada and later on in the UK.

Q: I asked this question because some months ago, when we inquired about how to file a specific complaint regarding Eritrea, we were told that that the U.S. State Department, for example, prefers to handle formal filings through its embassies. Meaning that evidence and other materials should be presented there and then the embassies would make certain recommendations, taking away any direct communications between groups or individuals who would like to file a specific complaint with the U.S. government. Is this still the case or has the procedure changed somewhat?

PD: That has been the case before, including in China, but it is changing. There is more direct communications with the relevant bodies in the U.S. instead of going strictly through the respective embassies, and I think we are going to see more of that. That is one of the things they are trying to establish. In the U.S. they have actually done it quite well, to make the process more user friendly, to allow to make filings more directly.

Q: So, NGOs and individuals can simply submit a filing via the e-mail address listed in the new guide you just released.

PD: Yes, but it is always useful to involve the local embassy anyway, most of the times at least. The more people involved the better. But I think it is important to make the filing by yourself instead of using an intermediary, because you also have more control of the process when you do it that way.

Interview: Susanne Berger (Washington, DC, USA)

Foto: Header-foto ©Christopher Burns; Peter Dahlin ©Peter Dahlin; Cover Page ©Safeguard Defenders.

Contact: info@fritz-bauer-blog.de

Peter Dahlin

Peter Dahlin is a human rights advocate and director of Safeguard Defenders, a human rights advocacy group with focus on Asia. In January 2016 Dahlin was arrested by Chinese state security agents in connection with his work for Chinese Urgent Action Working Group (中国维权紧急援助组), also known as China Action, an organization he founded in 2009. The group supported the work of lawyers and human rights advocates throughout China. Among other things, it provided financial aid and training to so-called “barefoot lawyers”, private individuals who advocate for the rule of law in China but who have no formal legal certification. These defenders of basic rights are often the only legal representation private Chinese citizens can afford. While in prison, Dahlin was repeatedly interrogated about his network of contacts and exposed to harsh treatment, like sleep deprivation as well as physical as and psychological threats. His forced ‘confession’ to fictitious crimes – including breaking Chinese law and “hurting the feelings of the Chinese people” – was recorded and aired on China’s State Television. He was deported from China in late January 2016. However, many of his co-workers and colleagues were detained and imprisoned in Chinas brutal detention system, called Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL).

Dahlin is the editor of Trial by Media: China’s new show trials and the global expansion of Chinese media (Peter Dahlin, Safeguard Defenders, 2018). He was also a main contributor to The People’s Republic of the Disappeared: Stories from inside China’s system of enforced disappearance (Michael Caster, Teng Biao and Peter Dahlin, Safeguard Defenders 2017). His latest publication is Fighting Impunity: A guide on how civil society can use Magnitsky Acts to sanction human rights violators (Safeguard Defenders, 2020).

https://safeguarddefenders.com/en/publications

More on the subject on the Fritz Bauer Blog

Should the EU adopt a Global Magnitsky Act? – As the EU is contemplating the adoption of an EU wide global human rights sanctions regime, leading international sanctions expert Professor Clara Portela provides important background and context for the debate

Interview by Susanne Berger (Washington DC)

The Global Magnitsky Act Shines Spotlight on Eritreas’s Human Rights Abuses – New international ‘smart sanctions’ allow for a swifter and direct targeting of human rights violators

By Susanne Berger