06.08.2018

The Problem of Nuclear Detection

‘It’s a bit like trying your hand at blindfolded Chess’

A recently retired U.S. intelligence analyst explains the difficult challenges experts face to contain the global nuclear threat

Interview by Susanne Berger (Washington DC, USA)

XX is an expert in the field of nuclear proliferation and radiation detection. A retired physicist and holder of eight technical patents, he taught physics at the university level for several years before joining the U.S. intelligence community as an analyst and technical expert. His identity has been withheld, due to U.S. security regulations.

SB: You are an expert on nuclear proliferation and radiation detection. Why does verification remain such a challenge? In earlier times, like during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, analysts obviously faced huge obstacles, even when trying to detect the delivery and deployment of the rather bulky hard ware, i.e. Soviet missiles. One would assume that the availability of much smaller and more sensitive devices has helped to make the task of detection and verification much easier.

SB: You are an expert on nuclear proliferation and radiation detection. Why does verification remain such a challenge? In earlier times, like during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, analysts obviously faced huge obstacles, even when trying to detect the delivery and deployment of the rather bulky hard ware, i.e. Soviet missiles. One would assume that the availability of much smaller and more sensitive devices has helped to make the task of detection and verification much easier.

XX: No, the task is just as hard or even harder, for a variety of reasons. Because as our technical options expand, so do the tools available for the other side. Our opponents are very clever at disguising their activities. One problem is that even today radiation sensors have to be placed in close proximity to the target, in order to detect radiation signatures. Meanwhile, there is only limited information you can gain from secondary sources or data, such as satellite imaging, atmospheric testing or certain surveillance options, such as listening devices or monitoring the acquisition of specific materials or chemicals that would indicate a country is engaged in the development of a nuclear program. Also, countries are increasingly adept at conducting tests at multiple sites, some of them mobile and heavily concealed. So, verification remains an enormous challenge.

SB: Numerous countries todayhave nuclear programs, including Pakistan, India, China, to name a few. How varied are these programsand what challenges do they pose for detection?

XX: They all pose very different kind of problems for analysts – from the terrain involved, the statesthey border, the system of government, to the enrichment techniques they use – centrifuges or reactors. Unfortunately, there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach or solution when it comes to detection options.

SB: With regards to the Iran nuclear deal struck in 2015 (Iran plus the U.S., U.K., France, China, Russia and Germany -eds.)- from a technical standpoint, how do you assess the pros and cons of the current Iranian nuclear agreement? Was it a flawed but helpful arrangement or “the worst deal in history”, as President Trump argues?

XX: It’s a very complicated issue. Generally speaking, access is always of key importance for analysts and so, in that sense, an agreement that provides for access is helpful.

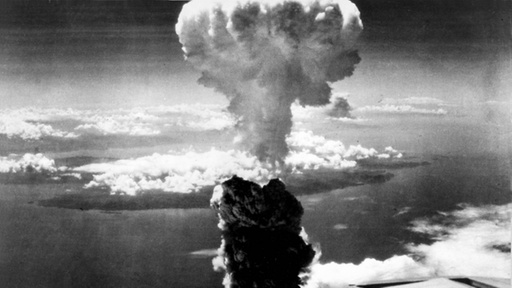

SB: We, the public, have very few realistic points of reference regarding the potential force of an atomic bomb or a nuclear warhead, other than what happened in Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Give me a sense of comparison regarding the bombs used against Japan in 1945 and today’s capabilities.

SB: We, the public, have very few realistic points of reference regarding the potential force of an atomic bomb or a nuclear warhead, other than what happened in Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Give me a sense of comparison regarding the bombs used against Japan in 1945 and today’s capabilities.

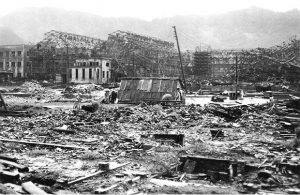

XX: The bomb deployed against Nagasaki was the more powerful of the two, an estimated 20 Kilotons. The damage caused by such a weapon varies, depending whether it is detonated in the air or on the ground. Roughly speaking, a 20 Kiloton bomb – a big number for an atomic bomb, most often one would deploy a two-stage hydrogen bomb – will cause immediate destruction of anything within a radius of about three quarters of a mile from the detonation point; a 160 Kiloton bomb will destroy everything within a radius of one and a half miles from initial impact. Concentric circles of damage caused by heat, pressure and radiation will extend far beyond this radius, causing severe injuries and health issues, due to radiation poisoning, as a well as extensive infrastructure loss, including hospitals, power stations, transportation and supply systems. The most powerful explosive we used to have was a nuclear warhead that sat above the Titan missile, of about 9 megatons (1000 Kilotons =1 megaton). Such a bomb will destroy everything within a six mile radius, a truly devastating force, especially if multiple warheads are deployed or a number of smaller warheads are used in combination. It all leaves you with an almost unimaginable scenario of potential destruction and chaos.

SB: As a leading expert on nuclear weapons and deterrence, what keeps you up at night – what worries you the most?

SB: As a leading expert on nuclear weapons and deterrence, what keeps you up at night – what worries you the most?

XX: I would have to say that it remains the worry about a nuclear missile getting into the hands of terrorists and other irrational actors, especially in countries like Pakistan. But you do not need a missile to attack the United States. You slip a small bomb in somewhere, and we are watching out for that. In more general terms, the most serious problems for experts is the need to reliably predict and assess explosive power of the missiles potentially deployed against us, as well as their accuracy. It is obviously very difficult to make such assessments when you do not have all the details – yet you have to get it right. This can pose serious headaches, because the most important issue for a defense analyst is to preserve second (retaliatory) strike capabilities. Apart from the purely technical concerns, there always exists the overarching challenge of reading other countries intentions correctly, to ascertain the specific doctrine governing their particular nuclear weapons program; in other words, to assess their real motives. It’s a bit like trying your hand at blindfolded chess. All that can cause some sleepless nights.

SB: What is the biggest misconception the public has about efforts to fight nuclear proliferation?

XX: Possibly the biggest misconception is that there exists a highly integrated, tightly coordinated approach within and also between countries to monitor and prevent nuclear proliferation. Some of these problems lie in the nature of the issue – detection and verification require great secrecy. But intelligence agencies are not the monolithic structures the public generally believes they are. There often exists a broad range of views among experts that are at times difficult to reconcile. Also, analysts can provide detailed technical information, assessments and advice but have little influence how this information is ultimately used or applied. The operational challenges are vast and extremely complex, as I indicated earlier. You can develop ever more sophisticated monitoring devices, but they also have to be properly deployed and then have to yield the data you hope they would yield.

SB: Is this one of the reasons why the verification process functioned so poorly during the second war in Iraq (2003-2008), especially in the early stages in 2003, when U.S. President George W. Bush, National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice and various experts claimed that Saddam Hussein was close to developing a nuclear weapon. You remember the famous quote “We don’t want the smoking gun to be amushroom cloud?”

XX: As I said, technical experts generally have very limited input and they do not control what information is provided to the top-line bureaucrats from other sources. In the case of Iraq, there were serious misinterpretations, like Iraq’s high-volume imports of certain types of aluminum tubes which – as it turned out – were not used in centrifuges (for enrichment of uranium). Similarly, the interrogations of Saddam Hussein yielded confirmation that he maintained an intentional ambiguity about Iraq’s nuclear program in order to intimidate his archenemy Iran.But don’t get me wrong: We obviously must confront the threats we face, as we suspect they exist. Admittedly, the process is far from perfect. However, it is a simple fact that our best efforts are driving up costs for the other side exponentially – and that aspect cannot be underestimated, especially for countries like North Korea, Iran and Pakistan.

SB: If nuclear weapons are hard to trace, then what about smaller amounts of radioactive material – because, as we know, even small amounts can inflict terrible damage. How optimistic are you that we can prevent ‘rogue’ usage of radioactive or highly poisonous chemical materials like Polonium -210 or nerve agents like ‘Novichok’, which were used in the attacks against Russian dissidents in London in 2009 (Alexander Litvinenko) and earlier this year (Sergey Skripal)?

XX: It remains a serious worry. The Polonium that killed Litvinenko was carried, undetected, on a commercial airliner. The existing methods of detection apparently did not pick it up. Polonium -210 has a half life of only 138 days but it is extremely radioactive. Other substances like Cobalt-60 or Cesium-137 in some ways pose an even greater danger, because their half lives are much longer – about five years for cobalt, thirty years for cesium. At the same time, one has to say that the release of such smaller amounts of radioactive material would only do limited damage to the general population. I am talking now purely in terms of damage control, regarding number of victims and lasting contamination. But the problem definitely exists.

SB: This brings up the widely discussed fear of terrorists obtaining the capability of building and deploying a so-called “dirty bomb” – a nuclear weapon constructed from radioactive nuclear waste material and conventional explosives.

XX: The one advantage of a dirty bomb, if one can call it that, is that it is relatively easy to detect, because it is highly radioactive. So, in that sense, I am not so concerned about this threat. A different problem involves the storage and transportation of nuclear waste. This poses some problems because several tons of nuclear material are moved on above-ground trains, for example. This calls for special measures, such as a securing the surrounding airspace, plus safe storage of the nuclear waste in special caissons. All this reduces the risk of an attack. And again, the expected damage would be limited – large in human cost, with a wide contaminated area, but not completely devastating to the human population as such.

SB: When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1990/91, there were widespread fears that the new government would lose control of its nuclear arsenal. Did you share this concern? How acute was the danger?

XX: It was quite serious and there were extensive discussions with Soviet scientists and other experts. Some of the Soviet republics could not guarantee the safety of their nuclear weapons and turned over control to Moscow. Obviously, a full-fledged nuclear confrontation would mean the end of both sides. The bad guys knew then and know now that this includes them. During the 1980s, the movie “The Day After” (made in 1983, about the devastating effects of a nuclear attack – eds.) was shown on Soviet TV. As President Reagan noted in his diary, the film had a deep personal effect on him and his Soviet counterparts. The threat of nuclear annihilation has kept the peace since the end of WWII – this is an undeniable fact.

SB: There has been talk in recent years of potential use of ‘low yield’ nuclear weapons, also referred to as “battle field” nuclear weapons in certain scenarios, even individual soldiers carrying such weapons. How realistic is such talk?

XX: Not very realistic – what you are referring to are so-called tactical nuclear weapons which already existed at the time the Soviet Union collapsed. Their use was intended for a specific purpose – against tanks, for example, to counter a Soviet tank invasion.

SB: What about Russian President Vladimir Putin’s recent claims of a whole new array of ‘invincible’ high-tech nuclear weaponry, including underwater drones and a new Russian ‘Super Missile” that supposedly flies at very low altitudes, with unpredictable flight paths, making it difficult to detect?

XX: One should take many of these claims with a healthy dose of skepticism.

SB: What was the most dramatic change in focus after 9/11, as it concerns nuclear proliferation? Give me a rough overview what the main concerns were before and after.

SB: What was the most dramatic change in focus after 9/11, as it concerns nuclear proliferation? Give me a rough overview what the main concerns were before and after.

XX: Even before 2011, there was a shift away from the nuclear threat posed by Russia, to a number of other countries such as Iran and China. After 9/11, the focus moved sharply towards fighting terrorism, supported, planned and carried out by specific individuals and a wide range of mostly foreign actors. Failed states played an important role in this. As always, solid on the ground intelligence collection is key to preventing an attack – if anything, since 9/11 there exists a heightened sense of urgency to ensure that the net of intelligence collection is cast as widely and effectively as possible.

SB: You have obviously followed the dramatic developments on the Korean Peninsula. Experts have different theories what is drawing Kim Jong Un to the negotiation table. One is that the economic sanctions have hit hard, forcing Kim to give up his policy of “byungjin” – the pursuit of both military and economic aims – in favor of simply pursuing economic strategies.

XX: It is quite possible that the sanction regime against North Korea is playing its part. But on the whole, I think that Kim is pursuing more or less a delay tactic, just like his father did before him.

SB: On a scale of 1 – 10, with 10 being the most dangerous, how serious a threat does North Korea pose to the U.S.?

XX: North Korea is a serious threat to South Korea and Japan – less so for the U.S. It remains doubtful whether or not it could deliver a nuclear warhead to the continental U.S. But regardless, any nuclear program in North Korea is unacceptable.

SB: In your view, what is the most important mistake to guard against in the continuing negotiations with North Korea? Or put differently, what is most important to gain?

XX: Time – that is the most important thing to gain. The most serious thing to guard against is impatience, and to offer reduction of sanctions without receiving a meaningful gesture from Kim up front. The general consensus among experts is that Korea is not ready to fully denuclearize. We can provide certain incentives, like economic and development aid, but, as I said, not up front and only in return for meaningful steps reducing North Korea’s nuclear capabilities.The most crucial aspect is, of course, verification.

SB: President Trump has set CVID as his declared standard – complete verifiable, irreversible denuclearization. What exactly does this mean? Would this also include peaceful means of nuclear power?

XX: If the North Koreans blow up their main 5 MWe nuclear reactor at Yongbyon, this would be difficult to rebuild. There have actually been reports from public monitoring groups that important updates continue to be made to the Yongbyon nuclear complex, including to the main reactor’s cooling system and other modifications. Whether or not North Korea should be permitted to harness nuclear power for peaceful means is a difficult question. They have been constructing a new 25 megawatt nuclear reactor (called the Experimental Light Water Reactor – eds.) – analysts are obviously watching this situation very closely. This also holds true for other associated projects, such as the Institute for Atomic Energy (IAE) in Pyongyang, which not only serves as a research facility for nuclear medicine, providing nuclear material (nuclear isotopes) and the technology required for health screenings and cancer treatments, for example, but also functions as a major educational and experimental facility for nuclear studies in general.

SB: Some weeks ago, North Korea blew up tunnels used for nuclear testing – at Mount Mantap at the Punggye-ri nuclear testing site in the northeastern region of the country, where all six of North Korea’s nuclear tests were conducted. The North Koreans also destroyed another important nuclear test site, seemingly indicating that Kim is serious about abandoning nuclear testing for good.

SB: Some weeks ago, North Korea blew up tunnels used for nuclear testing – at Mount Mantap at the Punggye-ri nuclear testing site in the northeastern region of the country, where all six of North Korea’s nuclear tests were conducted. The North Koreans also destroyed another important nuclear test site, seemingly indicating that Kim is serious about abandoning nuclear testing for good.

XX: On the whole I would say that this was little more than a publicity stunt – you can rebuild the tunnels or build a new site. Also, a major point to guard against is to ensure that North Korea is not transitioning over to alternative forms of enrichment, i.e. centrifuges.

SB: How do you assess the recent re-shuffling in the leadership structure of the North Korean Military. Is it an indication that Kim faces increasing opposition at home or even dissent regarding his stated intentions to abolish North Korea’s nuclear program?

XX: Frankly, my personal view is that this is a move more or less unrelated to the current talks with the U.S. It seems to me a move by Kim aimed to consolidate his leadership position in the regime.

SB: How do you view China’s role? Clearly, no permanent U.S.- North Korean nuclear deal can exclude China.

XX: Obviously, one cannot ignore the fact that China’s President Xi Jinping and Kim Jong Un have met at least three times in recent months – immediately before and after Kim’s meeting with President Trump. China undoubtedly is a key player, both politically and as a main (nuclear) proliferator. At the same time, we have to concern ourselves with each country individually first. Top North Korean scientists acquire their nuclear expertise in China – there is very little we can do about this. A similar problem exists regarding the training Chinese experts provide in the field of cyber espionage, but that is a separate issue. North Korea in many way continues to be an appendage of China. We do not know what exact influence or role the Chinese play in the North Korean nuclear program, so for now, we have no choice but to deal with these problem sets one at a time.

SB: You have been in the forefront of nuclear deterrence and the fight for non-proliferation the main part of your adult life. How would you sum up your views on the issue – what has stayed with you throughout?

XX: What stays with me is the awe-inspiring power of the nucleus – power that can be used for good and for bad. It really isup to us, science and society in general, to contain the risks and to harness this force in the most responsible andbeneficial way possible..

SB: Thank you very much for this conversation.

Interview: Susanne Berger, Washington DC, USA

Contact: susanne.berger@buxus-stiftung.de

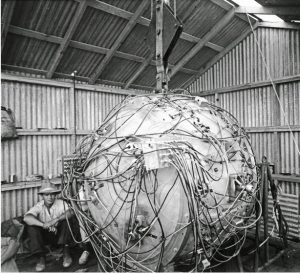

Photos: Header: public domain, CC-license; Fig. 1 The world’s first atomic bomb, named ‘Gadget’, 1945. Source: U.S. Department of Energy; Fig. 2 Mushroom clouds following the detonation of nuclear bombs over Hiroshima (left) and Nagasaki (right) in August 1945. The picture of the Nagasaki bombing was taken by Charles Levy from one of the B-29 Superfortressesused in the attack. Source: U.S. Department of Energy; Fig. 3. Photo taken by British Military Service man Cecil A. Creber, less than a month after the bombing of Nagasaki. Source click here; Fig. 4. Source: Youtube, Russian Ministry of Defense; Fig. 5 Overview of the 5 Mwereactor at Yongbyon, North Korea, Source: Airbus DS, www.38north.org.

For further reading

The first nuclear reactor called Chicago Pile -1 was built in 1942 by Enrico Fermi and his team, under the baseball stands of the University of Chicago

Remembering the Horrors of Nagasaki 70 Years later, National Public Radio, August 9, 2010

Sam Glasstone (ed.), Report on the effects of nuclear weapons 1957, U.S. Department of Defense and U.S. Atomic Energy Commission

Report from the Scottish Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament about the expected damage caused by nuclear war heads deployed by a Trident missile.

Abdul Kadeer Khan, the founder of Pakistan’s nuclear program, provided nuclear secrets to Iran and North Korea, The Washington Post, March 13, 2010