26.03.2018

The Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative RWI-70

The family of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg seeks answers to lingering questions about his fate with a new inquiry in Sweden

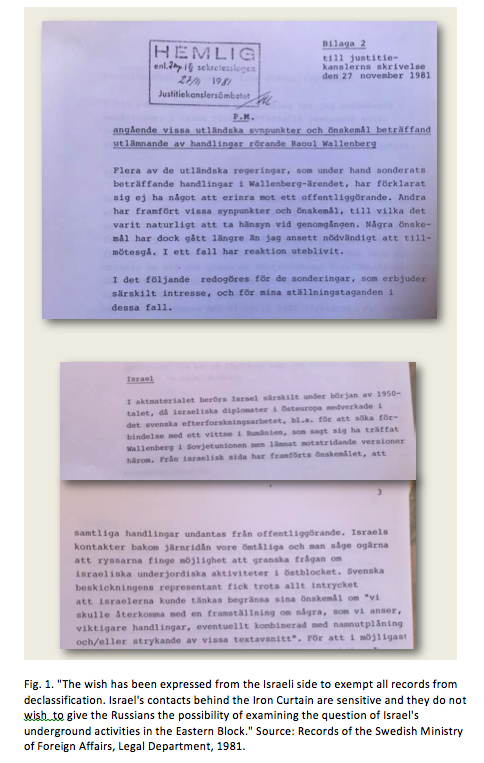

In 1981, the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs planned the declassification of a large set of records regarding the case of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg who had disappeared in the Soviet Union in 1945. In preparation for the release of documents, the Foreign Ministry’s Legal Department contacted several foreign governments to see if they had any objections to some of the information being made public.

In 1981, the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs planned the declassification of a large set of records regarding the case of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg who had disappeared in the Soviet Union in 1945. In preparation for the release of documents, the Foreign Ministry’s Legal Department contacted several foreign governments to see if they had any objections to some of the information being made public.

Some countries, including Israel, voiced concerns. Israeli diplomats asked that certain witness testimonies not be declassified, for fear that the information could reveal the Israeli intelligence services’ extensive espionage operations in Eastern Europe. The Swedish government tried to accommodate Israel’s request, releasing some of the witness statements in edited form and withholding others, some until as late as 2000.

The exchange raises several important questions: Did Sweden consult other countries, especially the U.S. and Russia, before declassifying records in the Wallenberg case over the years? If so, what information or documentation did these countries ask Sweden to keep secret?

Of great interest is the question if Swedish officials, in turn, ever approached Russia and other foreign entities to withhold specific information, concerning the Wallenberg case or Sweden in general, in their archive collections. This issue is especially significant for the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the Soviet Union was about to collapse and public access to Russian archival collections became possible for the first time.

Researchers want to know, for example, what kind of consultations Swedish officials conducted with Soviet officials before members of Raoul Wallenberg’s family visited the Soviet Union in October 1989, on special invitation of Chairman of the Supreme Soviet, Mikhail Gorbachev. Also, what discussions with U.S. representatives preceded the U.S. release of Raoul Wallenberg’s CIA case file in 1994? And how did such bilateral, behind the scenes exchanges affect the ten-year investigation of Raoul Wallenberg’s fate by an official Swedish-Russian Working Group during the 1990s?

Over time, it has become clear that Russian officials on numerous occasions withheld important information and documentation from certain members of the Swedish side of the Working Group, including Professor Guy von Dardel, Wallenberg’s brother.

There is mounting evidence that the suppression of documentation occurred intentionally. It must be urgently clarified what Swedish representatives have known about these actions and how they responded to the withholding of information by Russian officials.

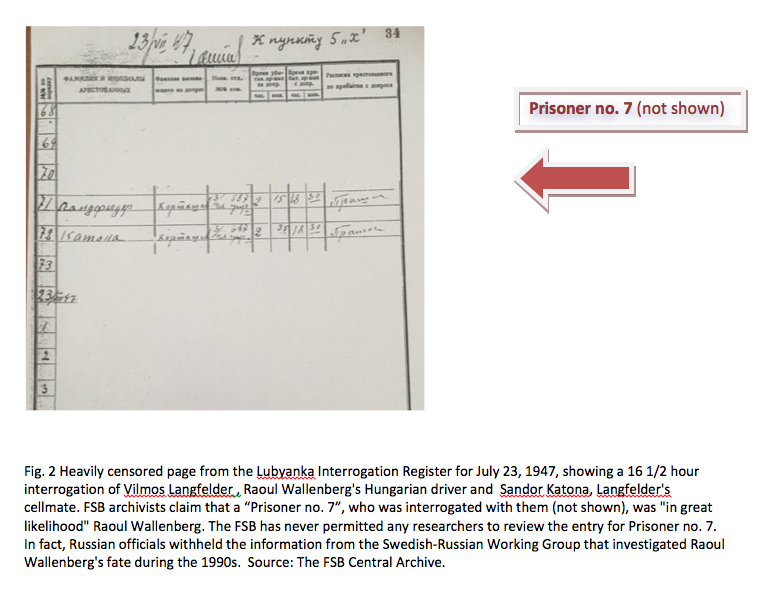

The censored records include documents that may prove that Raoul Wallenberg was alive several days after what Russian authorities claim to be his official date of death of July 17, 1947. Of special interest is an as yet unidentified Prisoner no. 7 who was interrogated on July 23, 1947 for more than 16 1/2 hours in Moscow’s Internal (Lubyanka) Prison, together with Wallenberg’s Hungarian driver, Vilmos Langfelder. According to archivists of the Russian State Security Service (FSB), this Prisoner no. 7 was “with great likelihood the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg.”

Russian officials clearly were aware of the information as early as 1991 (and probably long before that), but did not release it to researchers until 2009. So far, FSB officials have not permitted scholars and Raoul Wallenberg’s family direct access to the relevant documentation, so the information cannot be independently verified.

Ambassador Hans Magnusson, the Chairman of the Swedish side of the Working Group, was permitted to review the Lubyanka prison registers in 1991, but for reasons that are not entirely clear, he apparently did not notice the July 23, 1947 entry. Curiously, once the Swedish side learned about Langfelder’s July 23, 1947 interrogation, Swedish officials did not insist on a copy of the entry.

Ambassador Hans Magnusson, the Chairman of the Swedish side of the Working Group, was permitted to review the Lubyanka prison registers in 1991, but for reasons that are not entirely clear, he apparently did not notice the July 23, 1947 entry. Curiously, once the Swedish side learned about Langfelder’s July 23, 1947 interrogation, Swedish officials did not insist on a copy of the entry.

Just as surprising is the fact that Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt and Foreign Minister Carl Bildt, who received the new information regarding Prisoner no. 7 in late 2009, did not immediately demand a full clarification from the Russian government when they met with Russian President Vladimir Medvedev in November 2009 and again in early 2010.

After years of futile requests by scholars and Raoul Wallenberg’s family to the FSB Central Archive to permit access to the Lubyanka Prison registers for 1947, Marie von Dardel-Dupuy, Raoul Wallenberg’s niece, sued the FSB in Russia in 2016. The case is currently pending in Russian courts. The von Dardel family has now also filed a formal request with Swedish governmental and archival authorities in order to clarify what precise considerations determined the official Swedish and Russian handling of the Wallenberg case since 1945.

While Raoul Wallenberg’s mission to Hungary in 1944 was primarily humanitarian, his work also involved other aspects, ranging from contacts with the anti-Nazi resistance to the support of Swedish as well as foreign (U.S. and British) intelligence aims. If and how these additional dimensions of his activities contributed to his arrest and possibly to the handling of his case, must be studied in greater detail. Given Wallenberg’s official status as a Swedish diplomat in 1944, these actions would have constituted a serious violation of and direct challenge to Sweden’s official neutrality position.

New information suggests that in 1944, Raoul Wallenberg was not as inexperienced and unknown a figure as he has been generally portrayed and that he may have been groomed by the powerful Swedish bankers Marcus and Jacob Wallenberg (his cousins once removed) to fulfill a confidential role in the Wallenberg business empire.

At the time of Raoul Wallenberg’s disappearance, the Wallenberg brothers were among the most influential decision makers in Sweden, despite the serious problems they faced as a result of the official post-war U.S. investigation into their business dealings with Nazi Germany. However, there exists no indication that the Wallenberg brothers ever signaled to the Swedish government or to the Soviets that for them Raoul Wallenberg’s return was a key priority.

During the 1990s Swedish diplomats repeatedly did not push for disclosure of specific Soviet foreign and military intelligence records that could have provided important background information in the Wallenberg case. These include details about the Wallenberg business family and their activities during WWII, as well as Soviet intelligence reports from Budapest regarding the activities and contacts of Swedish diplomats in Hungary in 1944/45, including those of Raoul Wallenberg.

The missing pieces of information could shed much needed additional light on the question of what the Soviet leadership knew about Raoul Wallenberg and why Stalin decided not to release him. Of considerable importance in this connection is the question of what Wallenberg’s colleagues told Soviet officials about Wallenberg’s contacts and activities when they themselves were interrogated by officials of the Soviet NKVD. The information would help determine whether there was an active attempt at the time to distance themselves and, by implication, the Swedish government from Wallenberg’s work and contacts in Budapest.

The reports could possibly also provide an answer to one of the main mysteries in the Wallenberg case, namely why Staffan Söderblom, Sweden’s Ambassador in Moscow, failed to insist on full information about Wallenberg’s whereabouts at a time when the Soviet leadership had signaled a wish to improve relations with Sweden. Instead, Söderblom, simply asked Soviet diplomats in late 1945, and again in June 1946 – during a rare meeting with the Soviet leader Josef Stalin – for confirmation that Raoul Wallenberg had died as a result of an unfortunate accident in Hungary in 1945.

Why Swedish officials in general so readily accepted rumors that Raoul Wallenberg had died in Budapest in early 1945, when they had credible testimonies that he had been detained by Soviet forces and taken to Moscow, remains a question of central importance. New evidence suggests that in late April 1946, Stalin was not only eager to improve relations with Sweden but that he was willing to negotiate. Stalin instructed the Soviet Ambassador in Stockholm to offer the Swedish government a clear ‘quid pro quo’: If a Swedish-Soviet trade agreement were to be secured in 1946, “favorable conditions for … positive political Soviet-Swedish relations will be created. …“ The offer challenges the prevailing notion among scholars that the Swedish government was simply too afraid to push the Soviet Union for a clarification of Wallenberg’s fate at the time.

P R O T O C O L No. 50

(Special no. 50)

Of the POLITBURO of the CC VKP (b) DECISIONS from MARCH 6 – APRIL 11, 1946

From April 5, 1946

83. On our relationships with Sweden

[It is necessary] to make a move towards the Swedes and recognize the need to take the course for improving our relations with Sweden. For this purpose:

1. Charge Com.[rade] Chernyshev I. S. [Soviet Envoy to Stockholm] to make it clear to Minister for Foreign Affairs [Östen] Undén that in case of the successful development of the negotiations about the credit, favorable conditions for further positive political Soviet-Swedish relations will be created. […] [emphasis added]

CC SECRETARY J. Stalin [handwritten signature]

Fig. 3 Source: Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (RGASPI, Moscow). Fond/Collection 17. Opis’/Inventory 162. Delo/File 38. Listy/Pages 37-38.

One of the main aims of the new inquiry is to clarify if during the 1990s, Swedish and Russian officials truly intended to discover the full circumstances of Raoul Wallenberg’s fate or if their main intention was to solve the Wallenberg case just enough to allow its removal from the two countries’ political agenda. In particular, it needs to be examined in greater detail if Swedish and Russian diplomats intentionally kept the Wallenberg investigation within limited parameters, avoiding sensitive subjects (like the economic contacts of the Wallenberg family with Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in WWII, or the Swedish government’s support of Western intelligence aims during and after WWII), even though the documentation could have yielded important clues for researchers. The official search for Raoul Wallenberg’s fate in Russia obviously had serious implications for Swedish-Russian political and economic relations. Given these facts, it would be helpful to know what kind of discussions Swedish diplomats conducted with Wallenberg business representatives throughout the Wallenberg inquiry.

Surprisingly few Swedish foreign and military intelligence records regarding the Wallenberg case have been declassified since 1945. As a result, researchers have very little information about what internal considerations guided Swedish decision makers in their approach to the Wallenberg case over the years. Events such as the report of Swedish Professor Nanna Svartz in 1961 about her conversation with a Soviet colleague who allegedly claimed that Raoul Wallenberg was alive, the arrest of Swedish Air Force Colonel Stig Wennerström as a Soviet agent in 1963 and subsequently, the sudden emergence of new witnesses in 1979 that led to a formal reopening of the Wallenberg case (after it had lain dormant for a full fifteen years) should have given rise to at least some comment and assessment by Swedish intelligence personnel; as should have Guy von Dardel’s lawsuit against the Soviet Union in 1984 and the earlier mentioned 1989 visit by Raoul Wallenberg’s next-of-kin to Moscow.

Another issue that remains unresolved is whether ideological consideration affected Sweden’s official approach to the Wallenberg case. This includes the question whether or not the well known suspicions against prominent members of the Swedish government, including senior diplomats like Sverker Åström, a former Cabinet Secretary and U.N. Ambassador, of working for Soviet interests have been confirmed or not. Mr. Åström had a leading role in the Wallenberg investigation for decades, including the crucial years during the 1950s. His file is classified for 75 years in the Swedish Security Police Archive.

Even partial resolutions of these issues could provide important clues needed to finally solve the mystery of Wallenberg’s disappearance in Russia.

Kontakt: susanne.berger@rwi-70.de

Nyheter | Expressen: Raoul Wallenbergs familj ställer 80 frågor – kräver svar av regeringen