17.01.2020

75th anniversary of the disappearance of Raoul Wallenberg in the Soviet Union

FSB archivist express doubts about official Soviet version of Raoul Wallenberg’s death

75 years ago the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg disappeared in the Soviet Union. The full circumstances of his fate have never been revealed. A review of 40,000 newly released pages in the Raoul Wallenberg case file of the Swedish Foreign Ministry reveals that in 2011, high ranking officials of the FSB expressed serious doubts about the official Soviet version of Wallenberg’s death. They strongly suggest that Raoul Wallenberg was live six days after his official date of death. In fact, their statements to Swedish officials show that these FSB officers apparently consider the Smoltsov report – the note by A.L. Smoltsov stating that Raoul Wallenberg had succumbed to a heart attack in his prison cell on July 17, 1947 – either an after-hand construction or an outright fake.

Swedish officials already in 2011 received direct confirmation from the former deputy head of the FSB Registration and Archival Collections Directorate (URAF) and a veteran of the KGB/FSB Central Archive, Col. Vladimir Vinogradov, that Raoul Wallenberg was identical with a Prisoner no. 7 who was held in the Internal (Lubyanka) prison in Moscow in July 1947.

The information emerged as part of a preliminary review of the newly released 40,000 documents in the official Raoul Wallenberg case file of the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and documentation made available by Swedish officials, as part of the follow-up requests we placed regarding some apparent gaps in the released material.

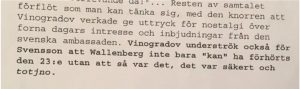

On October 12, 2011, Col. Vinogradov told a representative of the Swedish Embassy, Moscow during a screening of a Wallenberg documentary at the Sakharov Center, that “Wallenberg not only “could” have been interrogated on the 23rd [of July 1947], but that this was so, it was tochno [certainly so].” Vinogradov offered no supporting evidence for his claim. Swedish diplomats immediately reported Vinogradov’s statements to Stockholm, but Swedish officials apparently took no further action.

The new documentation also shows that a year later, in November 2012, Lt. General Vasily Khristoforov, at the time head of the FSB URAF and Mr. Vinogradov’s former superior, considered it “a possible hypothesis” that Raoul Wallenberg could be identical with Prisoner no. 7. Khristoforov made his comments in a meeting with Ambassador Hans Magnusson, the former Chairman of the Swedish side of the Swedish-Russian Working Group that investigated the fate of Raoul Wallenberg in Russian during the 1990s. Col. Vinogradov also was in attendance.

The new documentation also shows that a year later, in November 2012, Lt. General Vasily Khristoforov, at the time head of the FSB URAF and Mr. Vinogradov’s former superior, considered it “a possible hypothesis” that Raoul Wallenberg could be identical with Prisoner no. 7. Khristoforov made his comments in a meeting with Ambassador Hans Magnusson, the former Chairman of the Swedish side of the Swedish-Russian Working Group that investigated the fate of Raoul Wallenberg in Russian during the 1990s. Col. Vinogradov also was in attendance.

According to Mr. Magnusson’s memorandum of the discussion, Khristoforov freely expressed his personal view “that Raoul Wallenberg could have been alive after the [official death] date of July 17, 1947 stated in the Smoltsov Report, but in such a case only for a few weeks.” [Khristoforov was referring to the report by A.L. Smoltsov, head of the Medical Unit of the Lubyanka Prison, in which he claims that Wallenberg died of sudden cardiac arrest in his prison cell] Lt. General Khristoforov added that it was not possible to determine for sure if Raoul Wallenberg was identical with Prisoner no. 7 who had been interrogated for 16 1/2 hours, along with Wallenberg’s driver (the Hungarian citizen Vilmos Langfelder), since additional documentation was lacking. Khristoforov subsequently rejected Ambassador Magnusson’s request to review the original pages in the Lubyanka prison register for July 22 and 23, 1947, showing Prisoner no. 7’s calls for interrogation, citing Russian secrecy laws. Swedish officials did not seriously protest the decision and apparently did not pursue the issue further.

These episodes in 2011-2012 effectively sum up the core problem that has persisted in the Wallenberg investigation for decades. Russian officials, in particular those of the FSB, always emphatically claim that it is clear that Raoul Wallenberg died in 1947 and that they possess no more information or documentation that could shed light on the question of Raoul Wallenberg’s fate. They argue that the only way any progress in the matter can be made is if new details surface by accident. For their part, Swedish authorities have essentially accepted the Russian government’s position. As a result, the Wallenberg investigation has been stuck in a nearly complete impasse ever since 2000 when the Working Group concluded its official investigation.

Raoul Wallenberg’s family and researchers have argued for years that there are many reasons to be skeptical of Russian claims that no additional information at all exists about Raoul Wallenberg or his fate in Russian archives. If it is true that Russian officials have nothing to hide, why did they withhold the information about Prisoner no. 7 until 2009, when they have known about this information for decades? Did they feel that revealing this information would almost certainly attract unwelcome international publicity? Or, did they believe – as Lt. General Khristoforov phrased it – that the fact that Raoul Wallenberg was apparently alive six days after his official death date of July 17, 1947 was meaningless, because it did not alter the fact that Wallenberg definitely died in 1947?

This leads to the question: Do Russian officials actually know what happened to Raoul Wallenberg? The Smoltsov Report remains currently the only direct official information/document presented by Soviet and later Russian authorities about what supposedly happened to Raoul Wallenberg in 1947. Since its release in 1957, it has remained unclear when and where the report was found and exactly when it was created. The statements by Col. Vinogradov and Lt. General Khristoforov suggest that they apparently consider the Smoltsov document an after-hand construction or an outright fake.

It should be noted that since 1991, many Russian archivists have spent long hours attempting to answer the questions posed by researchers and Swedish representatives. It remains a fact, however, that not all Russian archivists and officials possess the same level of knowledge about the Wallenberg case. Similarly, many Swedish officials who come in contact with the issue lack a deeper understanding of the details of the case. This is especially true for the younger generation of diplomats and archivists, on both sides. As a result, the most precise and sensitive knowledge remains today confined to a very small circle of individuals.

Extensive document destruction definitely occurred during the mid-1950s, on the orders of the Soviet leadership, including the former first KGB Chairman Ivan Serov. At the same time, it has become very clear that Russian officials have more information about the Wallenberg case than they have previously shared with the public. This apparently concerns not only documentation kept in the FSB archives, but also in those of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Russian Military Prosecutor’s Office and the Presidential Archive.

We have already outlined many of the most pressing remaining questions and gaps in the official Wallenberg case record back in 2016. And just this past October Raoul Wallenberg’s family formally submitted an additional set of precise requests for documents and information to Russian authorities. As a result of the discussions between Wallenberg’s family and the Swedish Foreign Ministry in Stockholm in September 2019, the Swedish Ambassador to Moscow, Malena Mård, decided to formally take up the new submission with her Russian counter parts at the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This is a very positive development and a sign that Swedish officials appear ready to take a more direct and active role in the continuing efforts to establish the full circumstances of the fate of their famous diplomat.

One important example where more information about Raoul Wallenberg’s fate could be found are the files of the Russian Prosecutor General’s Office and the Military Prosecutor’s Office. Some months ago, Marie von Dardel-Dupuy, Raoul Wallenberg’s niece, requested all records regarding the decision by this office to rehabilitate Raoul Wallenberg in 2000. In response to the request, the Prosecutor’s Office replied that they do have records in their possession which they refuse to share with Ms. Dupuy. At the same time, the Prosecutor’s Office appears to refer to some information in its official statements about the case that Raoul Wallenberg was apparently shot to death. Even earlier, in 1997, Sergei Stepashin, former FSB Chairman in 1995-1996 and then Russian Justice Minister, stated the same to the press, when he accompanied President Boris Yeltsin on his official visit to Sweden. This version contradicts the previous official Soviet version of Wallenberg’s death of natural causes. These contradictions must be addressed and solved.

Raoul Wallenberg’s family and researchers cannot rely on assurances from Russian officials that some of the currently classified documentation from 1947 (the most crucial year in the Wallenberg case) will become available when the current 75-year classification period expires in 2022. Recent examples show that Russian authorities can simply extend the current secrecy designations, as just happened in the case of records related to the former Soviet state security official Pavel Sudoplatov. In response to our request to declassify an important memorandum [spravka, prepared by the Central Control Commission of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1968] related to the investigation of Pavel Sudoplatov activities as head of the “DR” (acts of terror and sabotage) Service of the State Security Ministry (MGB), the so-called Inter-Institutional Commission for Protection of State Secrets not only refused our request but extended the classification period to the year 2044!

Crucial questions also persist about one of the most important documents in the Raoul Wallenberg case, the so-called Vyshinsky Note about Raoul Wallenberg from August 18, 1947. It appears that the first copy (original) of this document that was sent to Stalin contained six pages. Pages 1-4 have not been released or missing. They possibly contain a formal summary of the Raoul Wallenberg case created at the time. Such a summary could provide essential clues as to the reasons for Wallenberg’s arrest and failure to release him. These pages should still remain today in the collections of the Presidential Archive.

Crucial questions also persist about one of the most important documents in the Raoul Wallenberg case, the so-called Vyshinsky Note about Raoul Wallenberg from August 18, 1947. It appears that the first copy (original) of this document that was sent to Stalin contained six pages. Pages 1-4 have not been released or missing. They possibly contain a formal summary of the Raoul Wallenberg case created at the time. Such a summary could provide essential clues as to the reasons for Wallenberg’s arrest and failure to release him. These pages should still remain today in the collections of the Presidential Archive.

The records of the Soviet Commissariat of Foreign Affairs (NKID) remain of special interest as well. They, too, contain records that were not previously shared with the Swedish side of the Working Group. These include, among others, the communications of the NKID with the Red Army General Staff and the Main Political Directorate of the Red Army (GlavPURKKA). They concerned the transfer of Raoul Wallenberg’s colleagues to Moscow in March-April 1945. It is quite possible and even likely that the documents also contain references to Raoul Wallenberg’s detention. The discussions in Moscow between the former Soviet Ambassador to Stockholm, Alexandra Kollontay and the Swedish Ambassador Staffan Söderblom also should be examined in detail. Kollontay could certainly not have acted without official approval of the Soviet leadership. Even though she was almost an invalid, she was still formally an official advisor to the NKID. She must have reported regularly about her interactions with Söderblom and she must have received specific instructions about these contacts.

A review of the previously classified interrogation protocols with former Soviet state security officials in 1991-1993 reveal that Wallenberg’s long-term cellmate in Lefortovo Prison, the German diplomat Willy Rödel, was initially held in Soviet imprisonment under the name of “von Oertzkhe”. This information was not presented in any documentation that has been released or published about Willy Rödel by the FSB. Apparently, this detail is given in the records that have remained inaccessible to researchers. One possibility is Rödel’s so-called “Working Agent File” (Agenturnoe delo), a separate file created by MGB investigators to collect reports of cell spies; according to FSB statements, these files have not been destroyed and should be kept classified forever.

The 40,000 new documents of the Raoul Wallenberg case file that were released by the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs last August contain another potentially intriguing piece of information. According to unconfirmed reports, a Russian documentary filmmaker (and possibly other sources) reported already in August 1989 that Soviet authorities intended to return Raoul Wallenberg’s personal possessions to his family. If true, this would be quite remarkable, considering KGB officials had claimed that they discovered Wallenberg’s possessions only in September 1989, by pure coincidence, in a storage room of the KGB archives. This claim must be examined further, because the exact circumstances of how Wallenberg’s possessions were in fact located in 1989 remains one of the biggest question marks in the Wallenberg mystery.

Another issue that remains to be addressed are the contradictory claims about the Investigation File of Count Mikhail Kutuzov-Tolstoy, who in 1944 worked with the Swedish Red Cross in Hungary. Kutuzov-Tolstoy, who after the end of the war worked for the Soviet military authorities in Budapest, was also interrogated extensively by Soviet state security officials. During the 1990s, Anatoly Prokopenko, the former head of the Special Archive (now it is the Russian State Military Archive), informed Swedish officials that he had a chance to briefly look through the documentation concerning Kutuzov-Tolstoy. According to Mr. Prokopenko, the file amounted to about 1,000 pages. He also indicated that Kutuzov-Tolstoy had reported about the activities of the Swedish Legation in Budapest, including those of Raoul Wallenberg. In contrast, Lt. General Khristoforov told Hans Magnusson in 2012 that he personally had reviewed Kutuzov-Tolstoy’s investigation materials and had found no information of interest for the Wallenberg case there. This contradiction, too, must be clarified.

All this once again underscores the pressing need for a systematic and independent review of original Russian archive documentation by qualified researchers. This was a serious shortcoming of the bilateral Working Group investigation. With some notable exceptions, Swedish officials often did not insist on obtaining direct access to key documentation or request verification of important pieces of information provided by the Russian side. For example, in 1993, Russian officials informed Swedish officials that the former head of the MGB Second Directorate (internal counterintelligence) Yevgenyi Pitovranov had personally interviewed Pavel Sudoplatov about the latter’s allegations that Raoul Wallenberg had possibly been poisoned in Grigory Mairanovsky’s toxicological laboratory. Pitovranov reportedly stated that Sudoplatov did not possess any information about Raoul Wallenberg. However, Swedish officials did not request a transcript of the interview, any notes or at least a formal interview report. They also did not include Pitovranov’s statement or Sudoplatov’s admissions in the Swedish Working Group report that was published in 2000, while the Russian side did.

Among the earlier material of the Wallenberg investigation one document that stands out is a protocol of a meeting that occurred in October 1981 at the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs that included Raoul Wallenberg’s siblings, Guy von Dardel and Nina Lagergren. At the time, a Soviet submarine was stranded in Swedish territorial waters. Wallenberg’s brother and sister pleaded and argued with Swedish diplomats to use the stranded sub and its crew as a means to press the Soviet leadership for the truth about Wallenberg’s fate. Swedish officials would only respond that as far as they were concerned, the two “incidents” were unrelated and would be considered as such. It makes an utterly depressing reading, even forty years later. The current renewed engagement of Swedish officials in the Raoul Wallenberg case is, therefore, all the more heartening and much more in keeping with Wallenberg’s extraordinary spirit, courage and determination – a powerful legacy that provided hope for thousands of people and will resonate for years and generations to come.

Contact: info@fritz-bauer-institut.de

Foto: Excerpt from a cipher fax of the Swedish Embassy in Moscow to the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Stockholm, October 19, 2011.