31.05.2018

Margot Wallström is in need of an Ombudsman

Peter Dahlin and Susanne Berger, on how to improve cooperation between the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the families of Swedish citizens who have disappeared abroad

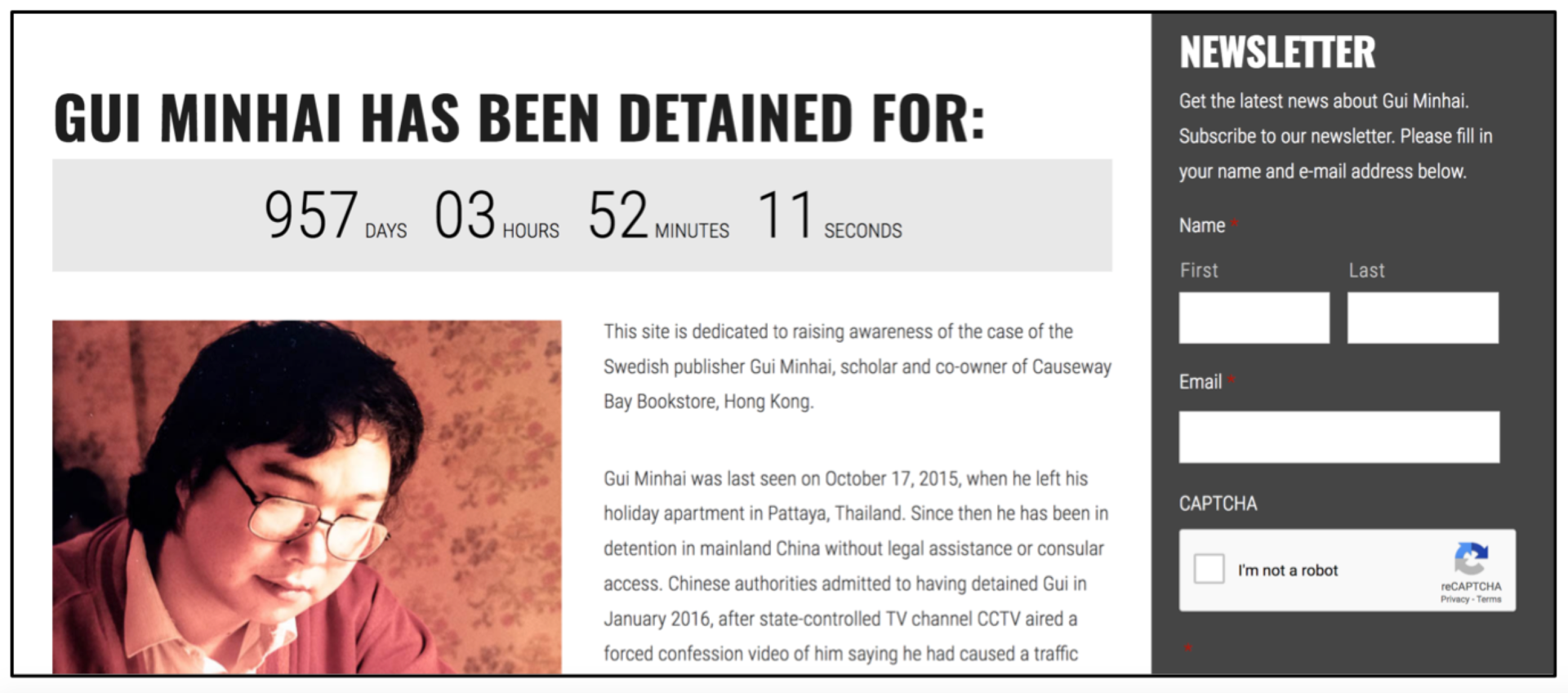

Why has the Swedish Foreign Ministry not done more for Gui Minhai? On March 27, we posed this question in a commentary published in Svenska Dagbladet’s blog “Säkerhetsrådet” (see also Hong Kong Free Press). In the article we took issue with the statement by Swedish government officials – specifically a comment by Foreign Minister Margot Wallström – that they have no effective way of countering China’s brutal treatment of Swedish publisher Gui Minhai. Gui has been imprisoned in China without due process or effective legal counsel since 2015 and his health has been seriously impaired as a result of his incarceration. He has been coerced into making false public confessions on Chinese TV three times. A recent report showed that these public confession are almost always the result of coercion, torture and threats to family.

Why has the Swedish Foreign Ministry not done more for Gui Minhai? On March 27, we posed this question in a commentary published in Svenska Dagbladet’s blog “Säkerhetsrådet” (see also Hong Kong Free Press). In the article we took issue with the statement by Swedish government officials – specifically a comment by Foreign Minister Margot Wallström – that they have no effective way of countering China’s brutal treatment of Swedish publisher Gui Minhai. Gui has been imprisoned in China without due process or effective legal counsel since 2015 and his health has been seriously impaired as a result of his incarceration. He has been coerced into making false public confessions on Chinese TV three times. A recent report showed that these public confession are almost always the result of coercion, torture and threats to family.

Ms Wallström did not respond to our article but we learned indirectly that she apparently considers our criticism unjustified. The Foreign Minister does have a point. Outsiders like us clearly do not have insight into all the facts and contingencies that come to bear in the case of Gui Minhai. Furthermore, Ms Wallström currently faces a tremendously difficult situation with regards to China – an economic powerhouse that is also turning ever more repressive.

Everybody is fully aware of the problem, while also recognizing the fact that Sweden must draw a line in the sand and insist on the welfare of its citizens, as a matter of principle and the law. The Swedish government does not have to fight this battle alone, however. The European Union appears to be an increasingly willing partner, evidenced, for example, by the emerging consensus among its most powerful economies on the need to establish a central monitoring process for China’s strategic investments in Europe, something Sweden has so far refused to support.Ms Wallström will soon have an opportunity to address these and other issues when she formally presents the Swedish government’s agenda for its upcoming turn as Chair of the U.N. Security Council. So, the discussion should center less on Sweden’s ‘weakness’ but instead focus on how to identify the best remedies available to counter China’s behavior.

The Foreign Minister and her colleagues should also possibly take a moment to put themselves in the position of the families of those who have disappeared. Swedish diplomats have to understand that family members cannot simply sit by and do nothing, especially when they encounter an official wall of silence. Relatives of the missing feel it is their moral obligation to do something, anything, to help their loved ones. They try very hard to take responsible and constructive steps, but more often than not these steps bring them in conflict with the very entities that should be their greatest supporters. The result is mutual distrust and a complete breakdown of communication. In the end, families feel like they are fighting a two-front war – which is both dispiriting and exhausting.

We have seen all this before. Maj von Dardel, the mother of Swedish Holocaust hero Raoul Wallenberg who disappeared in the Soviet Union in 1945, despaired at what she perceived was the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affair’s “callousness” and disinterest in the fate of her son. The families of the crewmembers of the Swedish DC-3 that was downed by a Soviet fighter plane in 1952 were lied to for years by their own government about the plane’s true mission. The widows were refused pensions with the excuse that the Swedish government had had “no fault” in the disappearance of their husbands – all official employees of the Swedish Armed Forces and the intelligence services who disappeared in the line of duty.

To its credit, the Swedish government appears to have drawn at least some key lessons from this dismal history. Swedish officials deserve great credit for managing the release of Swedish journalists Martin Schibbye and Jonas Persson in 2012 from Ethiopia and for patiently working to secure the safe return in 2017 of Johan Gustafsson, who spent more than five years as a hostage of Al-Qaeda forces in Mali. Just as importantly, this past February Ahmadreza Djalali, a researcher working at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute of Medicine, was granted Swedish citizenship – a move that will undoubtedly cast a shadow on Sweden’s relation with Iran.

And yet, there are moments one wonders if any lessons have been learned at all. Why did Swedish diplomats – including Ms Wallström and Sweden’s Ambassador in Beijing – flatly refuse to communicate with Angela Gui – Gui Minhai’s 24-year-old daughter – for more than a year after her father’s disappearance? In desperation, Angela Gui felt she had no choice but to travel to the U.S. to testify before the U.S. Congress. She also addressed the U.N. and the British Parliament to draw the world’s attention to her father’s plight. Likewise, Peter Dahlin was asked to speak before U.S. lawmakers after his release from ‘Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location’ (RSDL) – China’s extra-judicial system of secret imprisonment in which also Gui Minhai was initially detained. So far, no invitations have been extended to Peter Dahlin or Angela Gui – either by the Swedish Parliament or the Swedish Foreign Ministry – to share their experiences.

Just as difficult to understand is thefact that the Swedish government refuses to sanction or even investigate those individuals responsible in the Chinese state media for the serious violations committed against two Swedish citizen who were held under severe duress and paraded on Chinese State TV (CGTN) for propaganda purposes. Sweden raised no objections when in 2013 the European Council issued full sanctions against Iranian State Media personnel (for televising forced confessions). Meanwhile, Chinese government controlled media outlets continue to operate freely throughout Sweden.

But the Swedish government’s hesitancy to confront China is far from unique. The Swedish Foreign Ministry’s reaction to the illegal detention of Swedish-Eritrean playwright and author Dawit Isaak in Eritrea in 2001 has been equally troubling. For years, Esayas Isaak, Dawit’s brother, could not get Swedish diplomats to take any steps at all, despite the fact that Dawit Isaak – like Gui Minhai – is a Swedish citizen. Nearly 17 years later, Swedish authorities have not managed to learn Isaak’s whereabouts or his condition. No Eritrean diplomats have been expelled (with one exception) nor have any restrictions been imposed on their movements or activities in Sweden.

Obviously, Swedish Foreign Ministry and intelligence officials must be given sufficient time and space to do their jobs. Nobody understands that better than the families of the disappeared. But instead of trying to establish a workable relationship with family members and their advocates, officials all too often block all contact and information – creating a situation that leads to a self-enforcing cycle of anger and resentment. Undoubtedly Ms Wallström privately cares very much about Gui Minhai, Dawit Isaak and all other missing Swedes. At the same time, the government’s silence and perceived inaction – and worse, the often rather curt dismissal of all inquiries – in effect forces families into a corner.

It is not easy to find the right balance but an effort should be made to develop a semi-formal protocol how to handle similar situations in the future. For starters, the Foreign Ministry could appoint an official (‘ombudsman’) who acts as family liaison as soon as a Swedish citizen goes missing abroad, conducting regular meetings and providing updates about the case in question. The limited mechanisms that currently exist should be formalized and expanded. Relatives need to be adequately briefed about their rights, as well as the rights, duties and limitations of official Swedish entities. In short, families should be given a comprehensive and realistic assessment of the situation they are facing. Meaningful support could be provided, for example, in the form of ‘first aid’ kits, which could be developed in close cooperation between the Swedish government, human rights groups, former prisoners and their families, as well as volunteer legal representatives and other experts.

It would create a win-win scenario, helping all involved. It would help to reduce the risk of unnecessary misunderstandings and resentments. Most importantly, a more efficient cooperation of all sides will increase the chances for the positive outcome that all parties clearly want – to secure the release and safe return of Gui Minhai and Dawit Isaak.

Authors: Peter Dahlin is a human rights advocate, founder and former head of China Action (2009-2016); Susanne Berger is a historical researcher, founder and coordinator of the Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative (RWI-70)

Contact: susanne.berger@rwi-70.de

Photo: Screenshot from May 31, 2018, https://freeguiminhai.org