10.10.2021

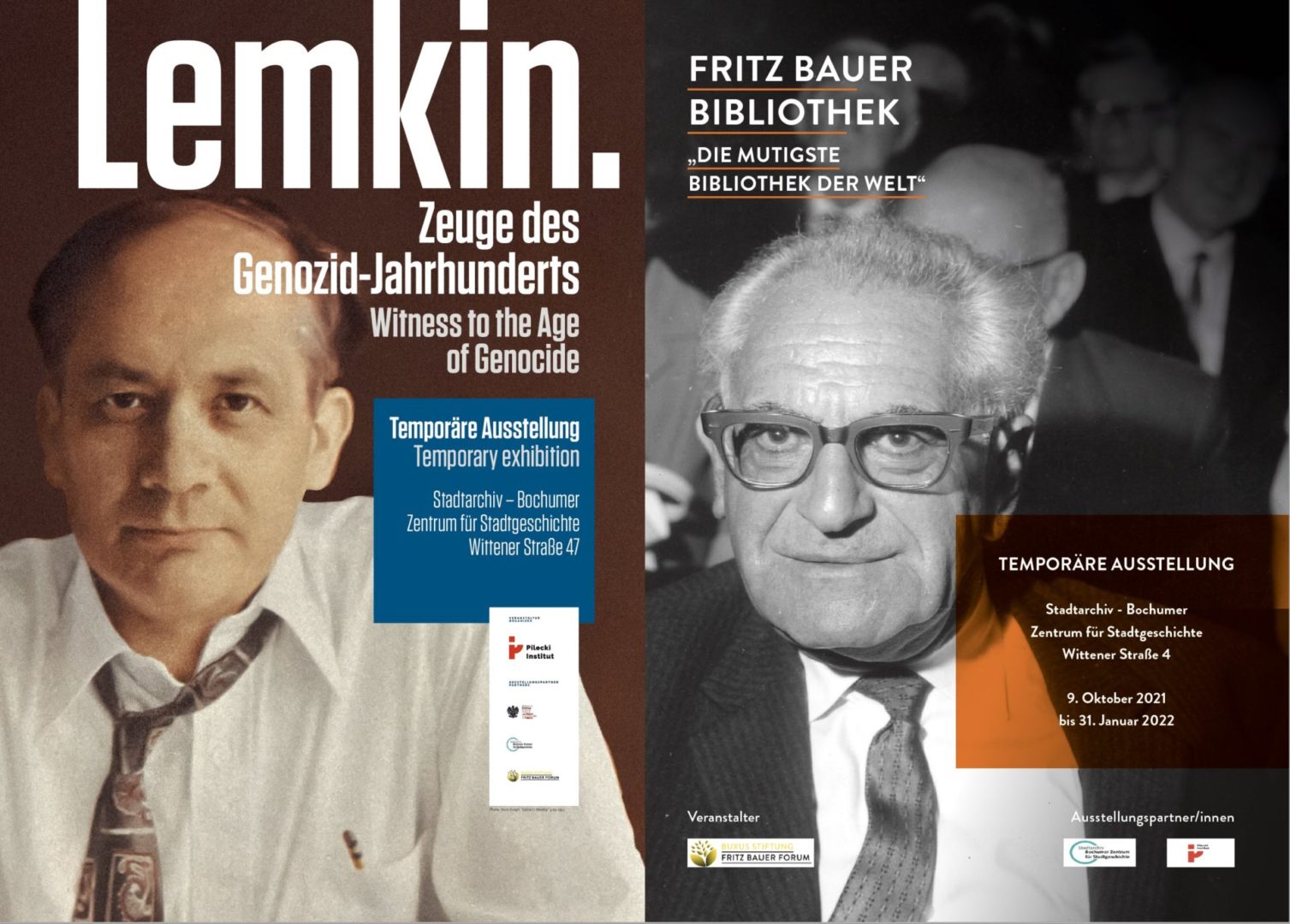

On the Opening of the Double Exhibition of the Pilecki Institute and the Fritz Bauer Forum in Bochum

Irmtrud Wojak

October 9, 2021

The exhibition will be on display at the Stadtarchiv – Bochumer Zentrum für Stadtgeschichte, Wittener Straße 47, until January 31, 2022.

When the Pilecki Institute invited the developing Fritz Bauer Forum to a collaboration last year, I already suspected that a joint project could emerge. Our conversation quickly turned to Raphael Lemkin and Fritz Bauer. We talked about the two lawyers’ resistance to National Socialism. It was about the lives and hopes of two courageous people who, in the face of an up to then unprecedented crime, relied on the further development of the law.

When the Pilecki Institute invited the developing Fritz Bauer Forum to a collaboration last year, I already suspected that a joint project could emerge. Our conversation quickly turned to Raphael Lemkin and Fritz Bauer. We talked about the two lawyers’ resistance to National Socialism. It was about the lives and hopes of two courageous people who, in the face of an up to then unprecedented crime, relied on the further development of the law.

Fritz Bauer and Raphael Lemkin – both of them sought ways to prevent genocide (genocide) in the future.

There was and is a connecting idea here. The stories and the work of two extraordinary people, their commitment to international law and human rights, which are the starting point of our research, have brought us together. And after all, what can inspire more than the lives and hopes of two people like Lemkin and Bauer, who refused to be swayed and risked their lives for the cause of human rights. Both were Holocaust survivors and political exiles. Polish citizen Raphael Lemkin (1900-1959) coined the term genocide based on his experiences and became the originator of the UN Genocide Convention. German citizen Fritz Bauer (1903-1968) coined the term Unrechtsstaat (unjust state) for Nazi rule. And he brought Nazi justice and the crime of Auschwitz to trial in the Germany of the failed denazification. In 1966, Bauer’s comprehensive article “Genocidium (Genocide)” appeared in the Handbook of Criminology on the convention brought about by Raphael Lemkin, to which the Federal Republic of Germany became a signatory by law on August 9, 1954.

What is special about Lemkin and Bauer, I think, is that they both acted “Ohne Auftrag“. “Totally unofficial” (“Ohne Auftrag”), is the title of Lemkin’s autobiography in German, which we published last year. “In the struggle for human rights,” is how again Fritz Bauer retrospectively described his work, the two extraordinary jurists were united by their perpetual search for the law in the face of what was then a nameless crime. Both contributed to changing the view of their own history and to broadening it.

This brings me to our exhibition here in the Municipal Archives, that is, to one of them, namely the presentation of our planned Fritz Bauer Library, which in turn was the beginning of our Fritz Bauer Forum, which is currently being built in Bochum (we will also hear more about the Lemkin exhibition).

The Fritz Bauer Forum, with its Fritz Bauer Library, is intended to provide insights into how the lives of people who seek justice and consequently resist or have to resist differ from the lives of people who watch or observe but do not actively participate themselves.

The Fritz Bauer Library has a radically new approach. Its starting point is that it is one thing to remember and commemorate the victims, and the other to honour the resistance. With this approach, the Fritz Bauer Library is not just a data repository, but actively reaches out to people. It has something to do with their lives by addressing current questions that are directed at each and every individual:

What strengthens people to stand up and raise their voices against injustice and violence, especially when most or even almost all of them remain silent and merely watch?

What are the conditions and therefore which conditions do we need to create so that particularly young people do not simply adapt and learn to obey, but rather develop the courage to put their humanity on the line? And precisely when it comes to defending human rights, one’s own and those of other people.

The German culture of remembrance, with its cultivation of a collective negative memory over decades, is considered particularly model-like. With regard to the until now singular crime of the Holocaust, it is internationally praised as a success story with a role model function for states in transition after a dictatorship.

Those who risked their lives “In the struggle for human rights” are remembered as victims within the framework of this remembrance culture. Their courageous resistance, on the other hand, is virtually absent from this historical narrative of the land of perpetrators and victims. Unadjusted lives like that of Fritz Bauer are thus put into perspective. Unlike Raphael Lemkin in the film Watchers of the Sky or Martin Luther King Jr. in the film Selma, Fritz Bauer is accordingly portrayed in German books and movies merely as a Nazi-hunting anti-hero, whereas in reality the focus should be on his extraordinary courage and struggle for human rights.

Those who risked their lives “In the struggle for human rights” are remembered as victims within the framework of this remembrance culture. Their courageous resistance, on the other hand, is virtually absent from this historical narrative of the land of perpetrators and victims. Unadjusted lives like that of Fritz Bauer are thus put into perspective. Unlike Raphael Lemkin in the film Watchers of the Sky or Martin Luther King Jr. in the film Selma, Fritz Bauer is accordingly portrayed in German books and movies merely as a Nazi-hunting anti-hero, whereas in reality the focus should be on his extraordinary courage and struggle for human rights.

In fact, it has become customary in the culture of remembrance to hardly remember the resistance – with the exceptions of Claus Schenk Graf von Staufenberg, Hans and Sophie Scholl, and perhaps Georg Elser on the anniversaries of their sacrificial deaths. Accordingly, political resistance and the struggle for human rights are even more rarely spoken about publicly. To describe Fritz Bauer’s path through life as a courageous history of resistance and his efforts as an advocacy for human rights, on the other hand, is rejected as heroic and sanctifying historiography. (2)

In fact, according to a recent survey (2019), only 5.3% of respondents still want resistance fighters from the Nazi era to be commemorated, while 49.4% think that “all victims” or “victim groups” should be commemorated. This deconcretization of the victim groups who were persecuted and resisted during National Socialism is also criticized in part. After the German-German reunification in 1990, however, the historical image of perpetrators here and victims there became a highly praised success story in the Federal Republic. (3)

Only recently have more and more responsible people become aware that this ” remembering crimes” on its own, which revives violence and thus also feelings of powerlessness and fury, can neither prevent a growth of racism and nationalism nor, as its flip side, anti-Semitism.

Nor can our liberal values and democratic structures be safeguarded from erosion in the long term and secured for the future by mere appeals to empathy and compassion for victims and survivors of terror and violence. Young people who have grown up with the image of history that has prevailed since the 1990s – perpetrators and bystanders here, victims and survivors there – have lost touch with history to no small extent. How could it be otherwise, when they are predominantly given the impression no one could do anything to counter the injustice and the violation of human dignity, and if someone did, it was in vain. Or, to put it the other way round, whoever did something against the tyranny ultimately became a victim, either as a lonely and abandoned antihero – like Fritz Bauer, who is supposedly portrayed as having committed suicide right at the beginning of the film “The State against Fritz Bauer” – or as a martyr, like Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, the siblings Hans and Sophie Scholl and Georg Elser, who ultimately paid for their resistance with their lives, which no one can be obliged to do.

Against this background, the American psychologist Eva Fogelman quotes Rabbi Harold Schulweis with the stirring question and answer: “In what moral code is it written that evil is allowed to eclipse good? What twisted logic leads us to erase the memory of the noble in man in order to preserve the memory of his degeneracy? If we excavate the criminal infamies, we must not therefore bury the virtues of humanity.”(4)

One can also put it this way: the history of crimes against humanity and genocide must not be forgotten, certainly not that of their victims. However, neither should the history of their struggle and resistance against human rights violations. The “Never again!” of the survivors is linked to the call to remember and also to the obligation to always stand up against nationalism and, as its flip side, racism, anti-Semitism with all means available in democracy.

Therefore, I am glad about the cooperation with the Pilecki Institute in the spirit of two pioneering jurists. The memory of their commitment to human rights gives rise to a new capacity for taking action. Mutual recognition can become practice, a common commitment to human rights.

Notes

(1) Fritz Bauer, “Genocidium (Völkermord) (1952),” in: ders, Die Humanität der Rechtsordnung. Ausgewählte Schriften.Frankfurt am Main, New York: Campus, 1998, pp. 61-75.

(2) The historian Professor Norbert Frei, for example, criticized Ilona Ziok’s film “Fritz Bauer – Tod auf Raten” (“Fritz Bauer – Death by installments”), saying that it caused a sensation because it insinuated that Bauer had died “possibly of an unnatural death”. “Activists of the much-invoked civil society,” Frei said, stylized a courageous prosecutor as a “lonely hero (…) with whose struggle for the punishment of Nazi crimes one can identify.” See N. Frei, “Fritz Bauer oder: Wann wird ein Held zum Helden?”, in Gerber, Stefan et al. (eds.), Zwischen Stadt, Staat und Nation. Bürgertum in Deutschland. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 273-279, here p. 275. Bauer “hagiography” outraged above all the former archivist of the Fritz Bauer Institute Werner Renz; cf. on this the review on publications by Renz’, who for lack of historical source critique already put numerous misinterpretations of Bauer into the world, by Irmtrud Wojak, “Fritz Bauer als Antiheld”, in Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen, 28. Jg. (2015) H. 4, pp. 377 f.

(3) Rees, J., Zick, A., Papendick, M., Wäschle, F., Multidimensional Memory Monitor (MEMO) II/2019. Bielefeld: Institute for Interdisciplinary Research on Conflict and Violence (IKG), Bielefeld University, 2019, p. 12.

(4) Eva Fogelman, Conscience and Courage: Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust. New York: Random House, 1995, p. 12.

Contact: info@fritz-bauer-blog.de